An Emotional Send-Off for Bo Dollis

Saturday much was made of Bo Dollis' iconic status, but the most emotional moments focused on Dollis, the man.

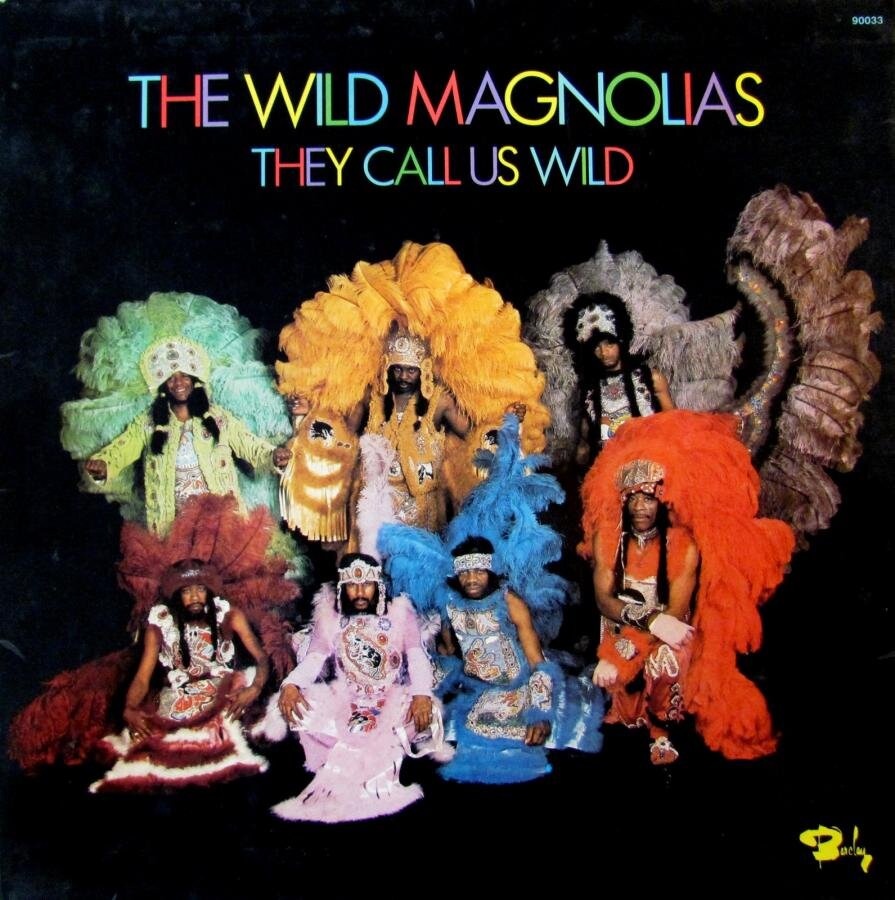

[Updated] No event with Mardi Gras Indians can be entirely solemn. Saturday at the funeral for Bo Dollis, Big Chief of the Wild Magnolias, more than 25 Indians came in their suits to pay respects, and their suits had few colors suitable for mourning. Instead, they stood in canary yellow, lime sherbet green, and a variety of purples. One Mardi Gras Indian with his back to me had a patch with a beaded image of Barack Obama and the cutline, “Mr. President.” They stood at attention but not exactly still, since even when they weren’t walking, the feathers on their costumes gently swayed with the breeze of the air conditioner.

Still, the service in Xavier University’s Convocation Center had some genuine gravity, partly from the powerful gospel music program that was a part of the ceremony, but also from the speeches recognizing Dollis’ accomplishments. Jazz Fest Executive Producer Quint Davis remembered first meeting Dollis in 1968 and encouraging him to record the first single of Mardi Gras Indian music, “Handa Wanda,” in 1970. Though composed as he remembered his relationship with Dollis in the ‘70s, Davis’ voice cracked with emotion when he concluded, “I was always proud to call you my Big Chief.”

Later in the ceremony, City Councilmembers James Gray and LaToya Cantrell came to the podium to announce that Council voted that Friday, April 24—the first day of Jazz Fest—will be “Bo Dollis Day” in New Orleans.

Mayor Mitch Landrieu spoke, saying, “Never forget the difference between who you are and what you are.” That thought was the slightly confusing cornerstone of his tribute to Dollis, which recognized the significance of Dollis as a Big Chief, as a civic leader, and as a musician. Landrieu also asked the question that has been on many minds this week: “Who will carry on?”

Are there Big Chiefs out there who want to leaders? Who want to make a difference? The hit New Orleans’ traditional neighborhoods took after Hurricane Katrina fractured the neighborhoods that Big Chiefs once represented, but are there Mardi Gras Indians who want to be meaningful members of their communities as well as colorful parts of beloved cultural tradition? Was Treme’s Albert Lambreaux a tribute to a figure leaving the New Orleans cultural landscape?

What Mardi Gras Indians lack in subtlety they make for with theater. Throughout the service, two Indians silently stood in front of the stage watching over the casket of the big chief. At regular intervals, two more would come to silently relieve them. When the family had visited the open casket one last time, Luther Gray of Bamboula 2000 began to play a simple, solemn drum pattern alone before being joined by a conga player and Big Chief Juan Pardo.

Much of that took place after many in attendance had gone outside to prepare for the release of doves and a multi-gang performance of “Indian Red.” They missed the most emotional moments because the ceremony focused on Bo Dollis, the cultural icon. When friends had to help Gerard “Bo Jr.” Dollis say goodbye to his dad for the last time, and Laurita “Queen Rita” Dollis’ sobs could be heard throughout the building as she cried over Dollis, it was a reminder that New Orleans had lost a legend, but they had lost a father and husband. One Mardi Gras Indian had been crying in the back of the Convocation Center, and when he was called upon to lead the casket out of the building, his war cries and shouts broke with emotion as well.

The circus outside the Convocation Center was a tribute to Dollis in more ways than one. The crowds of people and Indian gangs spoke to his importance, but the march he and Big Chief Monk Boudreaux made with The Wild Magnolias and The Golden Eagles in 1970 helped Mardi Gras Indians reach not just their neighborhoods but the culture at large. Mardi Gras Indians are no longer a community’s secret or a part of the city’s lore. They’re sufficiently accessible that a big chief could be one of the central figures in a national TV show, and well enough known that Win Butler and Regine Chassagne from Arcade Fire attended the parade.

It’s easy to fear that the popularizing of a tradition is the first step toward robbing it of its potency, and in light of changes to the neighborhoods that once spawned Mardi Gras Indians, it’s a fair concern. But when James Andrews performed “Jesus on the Mainline,” a man in front of me got out his tambourine and joined in. My first thought: Who has his own tambourine? Then as I looked around, I saw four or five more, all played by people who knew what they were doing. I can’t imagine another city where as many people own their own tambourines, bring them to public events, and know what to do with them. As easy as it is for us to see the normalizing forces at work in our city, it’s useful to remember that New Orleans remains a remarkable, individual place. The next breed of Big Chiefs won’t be the first to cross police lines and Mardi Gras parades because Dollis already did that, but those that have the ambition can still do great things—and so can we.

“He is us; we are him,” Councilman James Gray said during the service. “We are a special people.”

Updated Feb. 2, 9:20 p.m.

The event took place at Xavier's Convocation Center. References to the contrary have been corrected in the text.