A Love of the Unknown

Our favorite things this week include Mas Ysa, "Oil City Confidential," and Tim Quirk on the state of the music biz.

Mas Mas: The music world is not without anonymity, with the advent of sites like Soundcloud and Bandcamp making it easier than ever for anyone to make music. Getting discovered online can catalyze an artist's career in mere hours without any marketing, PR, or established commercial identity. My favorite anonymous hitmaker of the last year is Jai Paul, a U.K. producer and singer whose wonky, drugged-out crooners have made a critical splash without Paul ever revealing his identity to the world. It's become an endearing element, listening to songs on repeat without having any other point of reference or context.

More recently, I've been fixated with electronic producer Mas Ysa's debut single "Why," which premiered out of nowhere on Pitchfork last month to acclaim. It was particularly exciting since, months before, I saw the Brooklyn producer (real name Thomas Arsenault) open for Deerhunter at the Spanish Moon in Baton Rouge. His show was intense and unnervingly energetic, with Arsenault bellowing over twinkly, house-influenced synth lines. A Google search after the show offered little information, so I was happy to get more about Arsenault when his first-ever single was released. "Why" is oddly structured, at times dropping its driving tempo only to rev up again seconds later with even more power. I never expected it to stick with me this long, but it's become a constant in my current rotation. Arsenault's voice is powerful yet coated in regret and sadness, adding a bitterness to the song's bouncing production. Such promise in a debut single is amplified by the unknown — not knowing what might come next or when. (Brian Sibille)

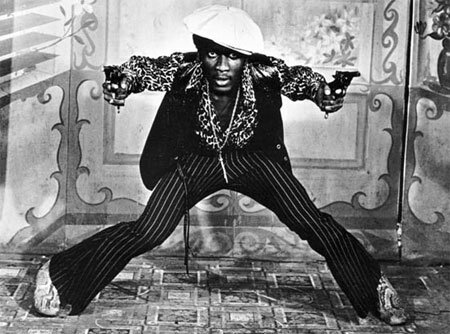

A Feelgood Story: Filmmaker Julien Temple has made documentaries on The Sex Pistols (The Filth and the Fury) and Joe Strummer (The Future is Unwritten). 2010’s Oil City Confidential is the prequel to those films, telling the story of the excellent but lesser-known Dr. Feelgood. It’s finally out on DVD, and while it helps to be interested in the band - which specialized in beer and amphetamine-powered R&B - it’s not necessary. Their story’s the narrative through-line, but the movie’s about early ‘70s British culture, particularly in working class, muddy, below sea level Canvey Island. Temple shoots the film with a lot of wit, style and craft, and he avoids the soapy tone that usually accompanies the hard times. Instead, he picks up on the band’s image by interspersing clips from British gangster movies, and hard, hard-drinking men don’t anguish over band tensions, no matter how real.

Those clips do more though. They also suggest how unlikely the band’s success was, and that it was like an audacious bank job that seems to work before it all ends in ruins. Throughout, the art direction is smart and richly visual. Footage of the band is impressive, particularly that of Johnson. I loved his choppy, abrasive guitar sound the first time I heard it, but he’s as charismatic and distinctive onstage. He’s the center of Temple’s story, and he’s as fully of life and vitality when the film was shot as he was in the Feelgoods’ heyday. He has pancreatic cancer and has refused treatment so that he can enjoy his last months, and this will be a great way to remember him. (Alex Rawls)

The Price of Music: Google Play’s Head of Global Content Programming Tim Quirk kicked the hornet’s nest recently when he said in a speech at the Future of Music Summit:

I’ve been in the online music business since there’s been an online music business and that article exasperated me so much because the writer was just repeating a Chicken Little cry I hear regularly and I heard it all morning long.

“We’re devaluing music!”

It’s amazing how often people invoke that word ‘devalue’ as if it means something. It doesn’t. You know why?

Because you can’t devalue music. It’s impossible. Songs are not worth exactly 99 cents and albums are not worth precisely $9.99.

When I hear people complain about discount pricing in online stores or fret about on-demand services such as Rhapsody and Spotify, I rebut them with another rule of mine that makes me sound like a hippie but I promise I’m not:

Music is priceless.

I mean that literally and I believe that even more than I believe old people should shut up about how much better things were in our day. Here’s why. The same song will always be worth different things to different people at different times.

The online conversation that followed DigitalMusicNews.com’s transcript of the speech gets wobbly in the way comments section conversations do - a lot of smug sniping, a lot of suspicion suspected until it takes on the strength of truth, a lot of attitude, and a lot of broadbrushing. Google’s bad, so if you work at Google, you’re bad. Quirk’s a smart guy on money, though, and he delivered one of the best presentations I’ve heard at the EMP Pop Conference when he talked about how his band Too Much Joy’s experience licensing a song to Pabst almost broke them up - but that the band’s relationship with the sponsor was far cleaner and more supportive than its relationship with its label.

Quirk’s vision of the future and better living through Google Play might not be the way forward, but his take on where we are today is spot-on. (Alex Rawls)