"Beauty and Power and Awesomeness"

Christopher King hears a world of beauty under the surface noise of pre-war Cajun 78s.

When Amanda Petrusich wrote about Amédé Ardoin for The Oxford American, she described Christopher King, the record collector and sound engineer who assembled Ardoin's collected works for the anthology, Mama, I'll Be Long Gone. She wrote:

On his office desk, alongside a big, outmoded computer, there's a green Remington typewriter. His eyeglasses are from another era. He doesn't own a mobile phone and refers to mine as a "smart-thing." His house in rural Faber, which he shares with his wife and daughter, is outfitted with an assortment of carefully vetted antiquities and oddities. Like many collectors, King has insulated himself from the facets of modernity he finds most distasteful.

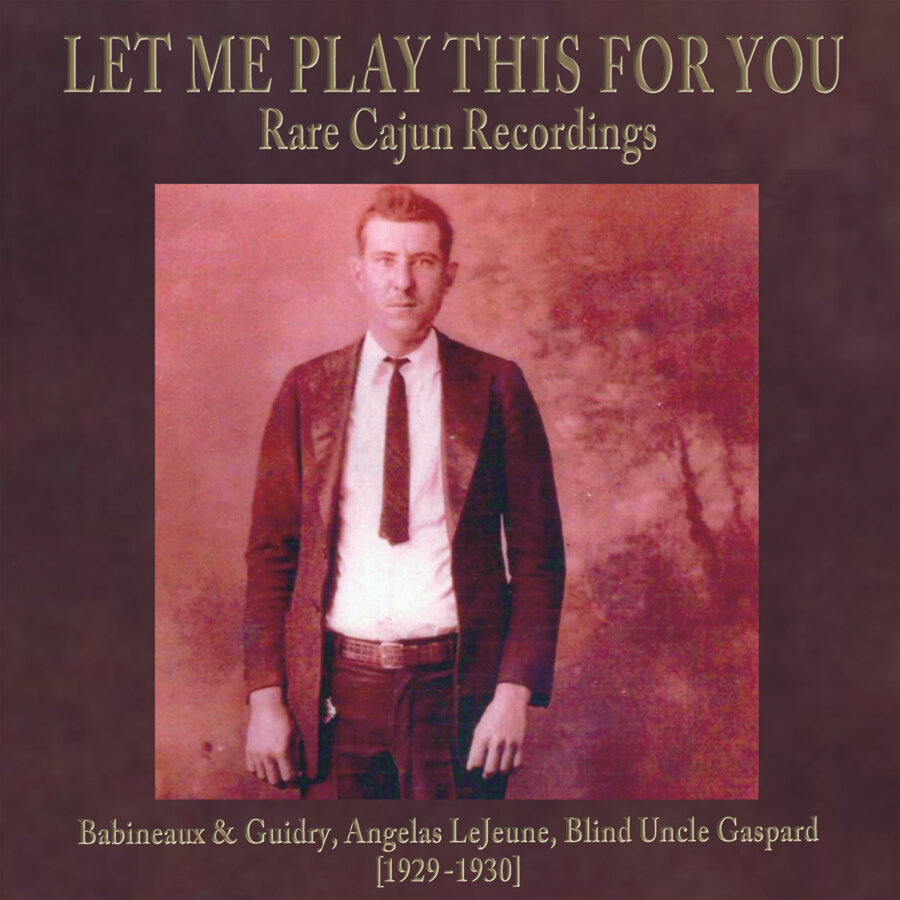

She describes King as a precise, intellectually helpful man, which is how I found him when we discussed the latest entry in his "Long Gone Sound" series of Cajun music reissues on Tompkins Square Records. Let Me Play This for You: Rare Cajun Recordings collected the work of Babineaux and Guidry, Angelas LeJeune, and Blind Uncle Gaspard, most of which came from two collections of 78s - his own and that of Ron Brown, who wrote co-produced the album and wrote the liner notes.

"If he and I were to combine our pre-war Cajun collections, we'd have 99 percent of all pre-war Cajun records in nice shape," King says. "He and I have a very friendly competition."

The series is part of an ongoing effort on King's part to help people appreciate Cajun music the way he does. "I feel that it is underrepresented and misrepresented to many degrees," he says. "In a way, I'm trying to re-cast it and re-brand it and re-present it in my purely subjective way of recognizing its beauty and power and awesomeness." In his mind, Cajun music has remained an undeservedly marginal part of the American music story - at least of the pre-World War II music that he focuses on. The superficial elements - the language, the instrumentation have caused people to overlook it. "They think it's very obscure, that it's not really a part of the history of American vernacular music. They don't know how to describe it, so they don't put it in the same category as, say, pre-war blues or pre-war black gospel or pre-war hillbilly. It's something different. What I'm trying to show in this project is that they're all bound up together. They're all part of the storybook of American music."

Let Me Play This for You attempts to similarly situate LeJeune and Babineaux and Guidry in the Cajun music story. "They are almost invisible in reissues of early Cajun music, yet they are tremendously influential both in the modern repertoire of modern Cajun music as well as the repertoire that developed in the '20s and the '30s," King says. "It was us trying to right a wrong."

He understands the impediments others have with pre-war Cajun recordings, but he doesn't share them. High school and college French taught him enough that he can understand many of the lyrics, and context helped him work out some of the Cajun French idioms. His own threshold for the ambient noise of the recordings is likely higher than others, so when he re-engineers the music for the collections in the series, "I have to remake it for the ears of the people," he says.

As for the content of the music, "You don't have to understand the lyrics to understand the pathos," King says. "That's the case with all traditional musics. They're geared to evoke or provoke a response from the human soul. It's something that transcends language." He counts off the beat to much Cajun music, "1-2-3-4-and-1-2-3-4. That 'and,' that elongation of that note, is meant to evoke sorrow when it comes to a waltz, or anticipation when it comes to a two-step or a one-step," and he hears similar musical decisions made in other pre-war musics. "You don't have to know what they're singing about or the narrative. The music itself is supposed to impact you, and that's the true quality of good music."

Similarly, the yowling, rural quality of the vocalists that some can find off-putting is crucial to their appeal for King. In those voices, he hears something distinctive and idiosyncratic - the sound of something real. "They all come from a country tradition, from an untempered vocal tradition," he says. "The polished vocals, the vocals that are refined and smooth - they really bore me."

King comes by his affection for the sound of 78s honestly. His father had more than 10,000 pre-war jazz 78s, and he started his collection of pre-war Cajun 78s when his grandfather asked him to clean out a sharecropper house on his land, and in it King discovered a dying Victrola with a wooden box of 78s, where he found Joe and Cleoma Falcon's "Aimer et Perdre" and some other Cajun 78s among a bunch of blues sides - "all Columbias, 1927, '28, '29," King says.

"I was immediately haunted by that music after my dad helped me wash the records and listen to them."

Not surprisingly, listening to 78s is his favorite way to listen to music. It's not the most efficient way, but King likens the steps involved - both necessary and personal - as akin to a religious ritual. "Pulling the 78 out of the shelf, cleaning it, getting the right stylus and the right speed and the right setting on everything. Having my wine with me and setting there and drinking it in for three and a half minutes. It's definitely a high that's not for everyone."

Working with these recordings for the "Long Gone Sounds" series has forced him to understand history and the music's context at a nuts and bolts level. When he thinks about how to present the music for contemporary audiences, he considers, for instance, where the tracks were recorded. In the Gulf South, humidity would have affected the recordings in pre-air conditioning days. Humidity adds fatness and limits the sound, so "you try to uncrack that fatness," King says. "You try to figure out, Well, this is what [Dennis] McGee's fiddle would have sounded like if you were five inches from him, and the same with LeJeune's accordion. Then you reevaluate that when you're thinking about somebody playing in Chicago or in New York."

The simple existence of these sides is another mystery King examines. His collection focuses on pre-war Cajun, early Albanian and early Greek recordings because all are equally improbable. These groups didn't migrate much out of their regions, so it's hard to imagine the business logic that drove record companies to release these recordings.

"Why record something that you could go next door and hear and participate in? What was the hook?" King asks. "It was a big, beautiful, bungling error on the part of greedy record executives. They thought they could exploit this thing for money, and in instances such as blues and hillbilly music, sure, that's possible because there were huge migrations of African Americans to Chicago. You have migrations of Appalachian musicians and listeners all over the United States, so they were able to record traditional folk music and to make big money off of it. With Cajuns and Albanians an Northern Greeks, not so much, and that's why their records are so tremendously rare. Inadvertently, those people whose eyes were on the greenback ended up preserving to me an unfathomable cultural heritage that would have been lost otherwise."

King's work largely demythologizes old recordings. He works to give them clear, human context instead of presenting the performances as unmotivated oddities. "I see that akin to the psychological neurosis that has pervaded us for the past 10 to 15 years, and I call it 'Hipster Exclusivity'," he says. "I like this because it's so obscure and so weird, and that's why I value it. Because of it's exclusivity. "I just don't think like that. I think this music is so overwhelmingly beautiful and powerful and tragic that it should be heard by more rather than less."

As much as his tastes and aesthetic lead him in traditional directions, he's aware that historical American roots music has often been presented with all the sex appeal of math homework. "They look like they're very specialized and for a niche audience," he says, and credits Art Director Susan Archie for the attractive design of the collections in the series. "You need to develop an eye candy. I'm trying to lure a wider audience in."

[Note: I assigned and edited Amanda Petrusich's story "Dragged Through the Forest" for Oxford American's 2012 music issue, which focused on Louisiana.]