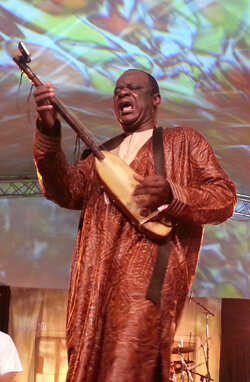

Voodoo: Diabate's Got the Blues

Cheick Hamala Diabate's music incorporates many sounds; the blues are just one.

"When you listen to Mali music, you hear a lot of different music inside, like salsa, reggae, Cheick Hamala Diabate says. "It's very old music. The music is so deep and so rich." As a jelli - a griot - he is a an oral historian and preservationist for his culture, and he'll perform Friday night at The Voodoo Experience.

"I really want to go back to Mali," he said during an interview a few weeks ago, but it's unlikely to happen any time soon. He has lived in Washington, D.C. since 1995, so he has not had to deal first-hand with the crackdown under Shariah Law in Northern Mali on music by militants and Islamic extremists. Instruments have been burned and musicians are threatened with amputation.

What's at risk is not only a remarkable musical tradition that has included such greats as Salif Keita, Ali Farka Touré, Vieux Farka Toure, Toumani Diabaté and Tinariwen, but the past itself since music is integral to the transmission of culture and history. "The music is about education," Diabate says. "A lot of things to tell people. When you listen to our language, the singing, it gives you a lot of power. Don't be lazy to your life. Do like your ancestors. If the government has a big, big message, they give it to the griots to tell to the people. The population trusts the griot more than anyone else."

As a jelli, he was raised in music, playing the n'goni - a predecessor to the banjo - since he was a child. "My town is a music town. Everybody play. Not only my family; many families." Music is a cross-generational activity as well, and children and adults play together. "Every family in Mali, every night we sit down from 8 p.m when we finish eating, make green tea, and play from 9 to 9 in the morning.

"Mali music is very old music," he says. "You can find a lot of things in Mali music." One of the most commonly heard elements is a proto-blues, and that has helped to shape how he's heard and understood in America. "I've been touring with a lot of blues and banjo players, and when I went to New Orleans for the Jazz Fest, I played with Little Freddie King. We went to sit down one evening. He played a couple of tunes and I followed him, then I do mine and he followed me. It was good. When I played with Little Freddie King, he was very easy to understand because he was like my family."

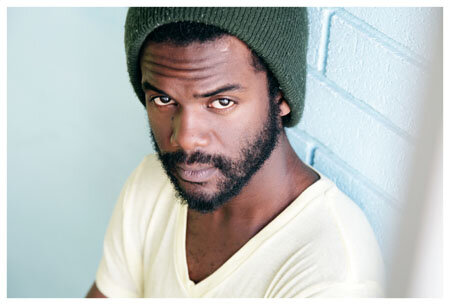

A month later, Diabate jammed with Gary Clark Jr. (who also plays Friday at Voodoo) at Floyd Fest in Roanoke, Virginia. "This day was a lot of raining, but you don't feel the rain," Diabate says. "People sat in the rain but nobody was moving. They felt the connection."

After Voodoo, Cheick Hamala Diabate will play at Chickie Wah Wah with Toubab Krewe. My Spilt Milk has a pair of free tickets to the show. To enter and have a chance to win, click here.

Related Voodoo Stories

Thomas Dolby and Life After Science