Third Man Explores Frank Stanford's Waters

The Jack White-founded publishing company presents the late Arkansas poet Frank Stanford through his typed and hand-written pages.

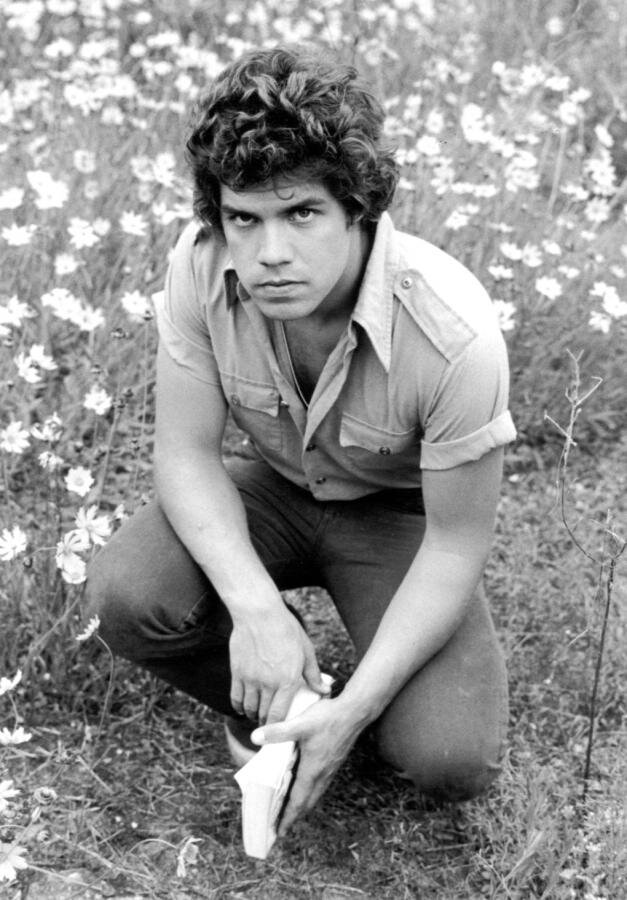

It’s hard to imagine a more fitting subject for a Third Man Books project than the poet Frank Stanford. He’s not quite poetry’s Robert Johnson, but the Mississippi-born Arkansas native’s work reaches beyond poetry’s converted, just as Johnson was a gateway bluesman. Stanford also comes complete with a legend of writing, romance and recklessness. He’s a character as much as a poet, and one of his romantic entanglements was with Lucinda Williams, whose “Sweet Old World” and “Pineola” are two responses to his suicide in 1978 while she was one of the women he was seeing—along with his wife Ginny and poet C.D. Wright.

His writing was aggressively southern. His book-length poem The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Lovebegins, “tonight the gars on the trees are swords in the hands of knights,” and he dives into backwoods grammar and vocabulary so quickly, completely and unapologetically that he achieves the same immersive effect that Cormac McCarthy achieved with his archaic language of antique technology in Blood Meridian. His poems evoke a world and they collectively chart one with the same assurance of a land surveyor—the gig he did for a living.

Stanford’s physical objects themselves are also up Third Man’s alley. The Jack White-founded company has shown a clear affection for the tactile experience of culture consumption, whether it’s vinyl-only releases, the two-volume Paramount Records Wonder Cabinet—two suitcase-sized wooden boxes that each weigh more than a three-year-old—or Neil Young’s A Letter Home, recorded straight to crackling, dusty-sounding vinyl at Third Man in a Voice-O-Graph. The first printing of Stanford’s Battlefield … is almost an inch thick, and the grain on the paper used for the first edition of his other books published by Lost Roads is so pronounced that it could almost be read in braille.

In April, Copper Canyon Press published What About This: The Collected Poems of Frank Stanford; last week, Third Man published Hidden Water: from the Frank Stanford Archives, and the nearness of the two publication dates is not coincidental. Michael Wiegers found himself overwhelmed by the possibilities as he worked to edit the book that became What About This. When Nashville poet Chet Weise approached him about some sort of collaborative effort between Copper Canyon and Third Man, Hidden Water slowly took shape. What started as a home for the overflow from What About This took on its own integrity as it, appropriately, leaned heavily on reproductions of Stanford’s typed and handwritten pages, often complete with scratch-outs and edit marks for subsequent revisions. The texture of real life that Third Man seems to value in its other projects is equally present in Hidden Water.

Although Hidden Water began life as a plus-one, it will certainly be an introduction to Stanford’s writing for those who take White and Third Man’s affiliation of a stamp of approval—and they could do a lot worse. Some work pages look too much like work pages to say anything, and the letters may require readers to already care, though they do reveal a curiosity about how the poetry business works that’s touching considering he was first published at 15 and wrote compulsively. But many of the short poems offer up foot holds into Stanford’s work. “Songs With No Words” reads:

the tongue

of the mule is bored

with the fits

and rages of farmers in love

and so it holds the years

of yours

lets bitterness

go and has no friends

More than the signature backwoods imagery, the beauty of the poem is the way the language of each line seems to spring the next. Stanford’s not writing automatically or in any dada manner, but the language and not a preordained overarching thought dictates what comes next. Because of that, it seems like Stanford is finding the poem at the same time you are, and the rush of discovery is hardwired into the poem itself.

For me, his shorter works frequently feel artificially truncated, kept deliberately tight with a marketplace in mind. I find Stanford most compelling when he lets that line-begets-line dynamic flow until the poem takes on an incantatory quality that comes together as a distinctly rural, American surrealism. Images pile up until one has the weight and momentum to push all the others aside so that he can start over. “The Mind Reader” is a Tetris tower of treble hooks, chain gangs, radio hep cats, and movie house petting, and its coherence is unmistakable.

Longer poems are also where Stanford is at his most musical. Hidden Water includes an inventory of his record collection—mainly jazz, with few surprises—and his writing is at its most kinetic in a passage like this one in “The Mind Reader”:

I dream of wide-eyed babies in jars of formaldehyde

I dream of submarines

and men suffocating in their own blood

I dream of the filthy moon

where the rifles are stacked like the harvest is over

the riverboat men boiling crawdads in the shanties

and I dream about mermaids’ hair

there are women driving Cadillacs to Memphis at tremendous speeds

my dog died a long time ago

look at the teeth of the piano on the highway

there’s no money under my pillow

only the unwinding rope in the fathoms of sleep where I give my only commands

to the water

The poem itself reads like notes for The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You and might be an excerpt (I can’t re-scrutinize 450 pages to find it & will take the word of anyone who knows); it’s certainly from the same world and the same story, down to shared details. Hidden Waters shows Stanford sharing images and tropes from poem to poem, but it never reads like an imagination bumping into its limits. Instead, those moments appear to be someone trying to find the best use of a construction or trying to get closer to the magic he knows is in a phrase. Or, that a device has more to give if he’ll just give it a chance.

In The New York Times Review of Books, David Orr wrote with mixed feelings about Stanford and What About This. “At his best, Stanford musters an admirably off-kilter intensity,” Orr deals—fairly—with Stanford’s more overheated writing, including a few more descriptors of the moon than big boys probably need.

Orr continues:

The goal, for a poet like Stanford, is to create an atmosphere of feverish surrealism in which categories like “good and “bad” buckle under the mysterious force of the creative drive itself.

He does not believe, as he puts it, in “the techniques of self-conscious poetics.” It’s an almost touchingly literary project, because it assumes writing could somehow become equivalent to the experience it describes—as if, by turning the flame down low enough, one could transform steak into a living cow.

Put aside paternal condescension and Orr’s right. Stanford’s faith in capital-P Poetry is religious, and it’s clear in his letters that he’s dismissive of those who’d subdivide it into poetics. When he was offered a scholarship to attend the American Poetry Festival with such poets as Ted Berrigan, Gregory Corso, Diane Wachowski, Robert Creeley and Jackson Mac Low, he confessed that he hadn’t read much of their writing. “I think they might be some of those poets who school up on theories and shit like minnows,” he wrote in one of his letters.

The beauty of Hidden Water is that by presenting physical evidence of Stanford’s existence, he’s less legend and more real. That gives readers a relationship to him and his work that even friends had a hard time getting when he was alive. In his appreciation of Stanford that opens the book, poet Steve Stern writes, “Though I considered him my friend, I didn’t know him well. I had too much awe and envy for the legend to relate without pretense to the man.”

The book includes a link to a Soundcloud file of Stanford reading, so readers not only get his voice on the page but as it sounded, and it’s more or less what you’d expect. He adopts the poetry cadence that treats every line like sacred script, but mentally adjust for the reading’s mannered quality and his voice reveals someone who worked to be brilliant but is not extraordinary. Someone real, and someone who needed to turn down the opera music playing in the background but thought it sounded cool at the time.