The Last Masks of David Bowie

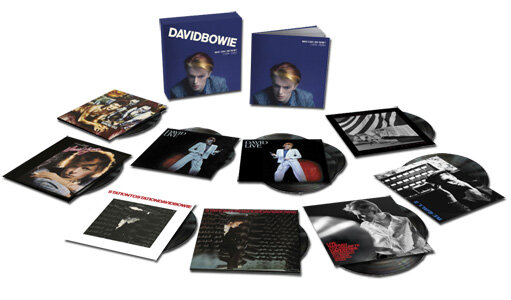

The new Bowie box set, "Who Can I Be Now? (1974-1976)," shows him discovering the limits of persona-driven music.

The new Bowie box set, "Who Can I Be Now? (1974-1976)," shows him discovering the limits of persona-driven music.

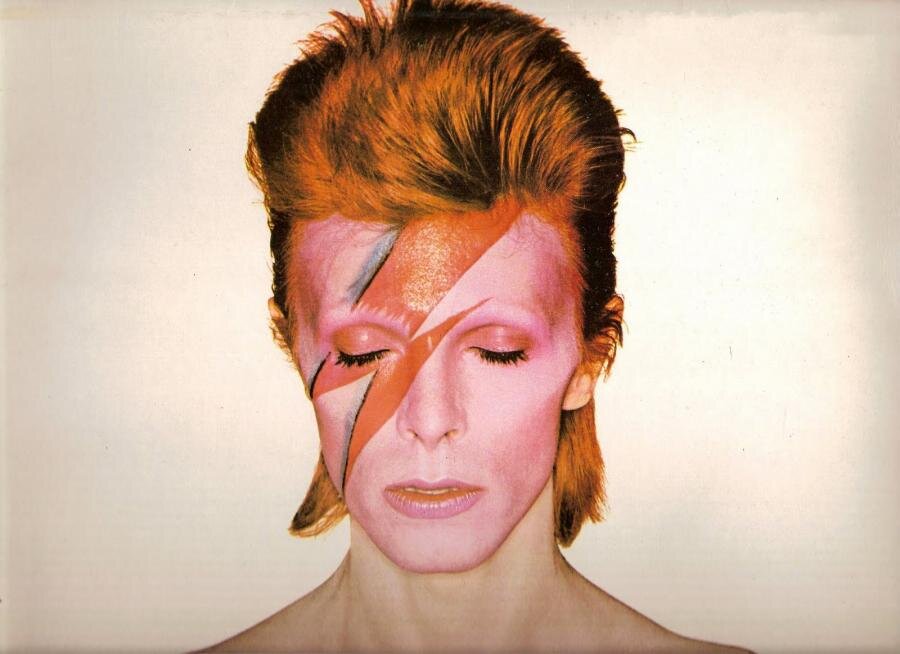

David Bowie’s appearance on The Dick Cavett Show in 1974 was always going to be odd. Cavett had established himself as an interviewer comfortable and capable with a broad range of subjects, from political thinkers to writers to rock ’n’ roll musicians. Before Bowie, he’d hosted Janis Joplin, The Jefferson Airplane, Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder, and John Lennon and Yoko Ono, and Cavett gave them a fair shake, taking them at face value as much as possible instead of treating them like freak shows—the more common way mainstream television treated musicians. At that time though, Bowie’s self-consciously unconventional career was always going to seem at least slightly odd. No one before him had gone through a series of personas, and certainly none that were as visually, musically, and sexually provocative as his. Try as he might, Cavett couldn’t treat Bowie like he was perfectly normal.

Bowie didn’t help. He began by performing funky versions of “Young Americans” and “1984” with bright red hair while wearing a brown suit with exaggerated shoulder pads—actually, the shirt underneath housed the pads, we learned later—and a plaid tie that cuts off abruptly when it meets the high waistband of slacks.

The performance featured the band that recorded Young Americans, including David Sanborn on sax and Luther Vandross in a denim leisure suit on backing vocals. It was the most conventional part of Bowie’s appearance. Once seated opposite Cavett, the painfully thin Bowie sniffs constantly and plays with a cane he picked up between the end of the performance and sitting down. He nervously strokes its handle and traces patterns on the floor with it while quietly, feyly answering questions. Eventually, Cavett had to ask him about whether or not he was nervous, which he copped to, but it’s impossible to watch and not think that his distant oddness was about more than just nerves.

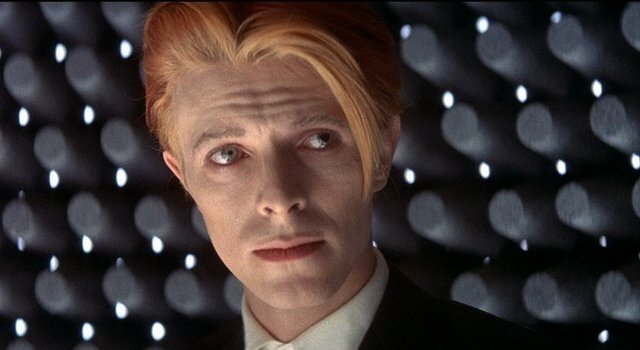

Now we know Bowie was a mess, and the last thing he needed at the time was to be on television. Between cocaine addiction and starving himself, he was going through a slow motion breakdown that would culminate with Station to Station and the filming of the Nicholas Roeg film The Man Who Fell to Earth. The new box set, Who Can I Be Now? [1974-1976], documents his output during that time, and the remarkable thing considering its historical context is that it’s not a wipeout. In fact, the box actually tells a good story.

It begins with Diamond Dogs, which today sounds like Bowie disappearing up his own ass. When he let go of the band he had played with for years including guitarist Mick Ronson, he seemed to let go of memorable melodies and songs as well as even a hint of restraint. The album’s best moments—“Diamond Dogs,” “1984,” “Rebel Rebel” and “Sweet Thing”—are strong enough to hold up under the conceptual and musical weight that Bowie piles on them, but others rely on the post-apocalyptic science fiction narrative to prop them up. Unfortunately, the lyrical debts are too obvious—to William Burroughs, first—and the musical charms too slight. Diamond Dogs is the sound of Bowie’s career trajectory to that point slamming to its inevitable conclusion. The 27 year-old singer had cycled through identities and theatrical concepts for the six years before with a seemingly unerring touch. Why wouldn’t he think that a fully realized stage show was the natural next step?

The rest of Who Can I Be Now? [1974-1976] is the sound of Bowie trying to figure out what to do next The box set’s title comes from a song he recorded in Philadelphia at Sigma Sound for a soul-based album that was never released, Gouster. Who am I if I’m not a character? He doesn’t exactly find the answer, but the semi-successful stabs are a tribute to his fundamental musical wisdom, even while losing his mind.

Bowie followed Diamond Dogs with David Live, which is represented in Who Can I Be Now? by two different mixes, neither of which solve the problem of his incredibly mannered performance—even by Bowie’s standards—and a band that was just starting to usher him into the world of Black music. A recent issue of Wax Poetics tells the story of Bowie’s effort to record with TSOP to get their urbane soul grooves. Not surprisingly, union musicians accustomed to working all day weren’t eager to shift to Bowie’s nocturnal schedule, particularly for an artist who had largely been a weird novelty to mainstream America at that point. Still, with the help of then-girlfriend Ava Cherry, he assembled a band that included Sanborn, Carlos Alomar, bassist Willie Weeks, piano player Mike Garson, and drummer Andy Newmark to record Gouster, the album that Bowie cannibalized to make Young Americans when a late night session with John Lennon led to “Fame.” It opened the door to new songs including a version of “Across the Universe” that hasn’t improved with time. (In the liner notes, producer Tony Visconti says he didn’t get it either, and thinks Bowie only recorded it to please Lennon.)

The Guardian’s Alexis Petridis hears the uncertainty and dissolution Bowie was experiencing in his personal life in Gouster:

A … sense of insecurity and ambiguity haunts “It’s Gonna Be Me,” clearly inspired by the stark, intense, gospel-infused soul that emerged from studios in America’s deep south rather than the luscious, forward-thinking music released on Philadelphia International. It starts out as a bit of serial seducer’s braggadocio – “I balled another young girl last night” – and gets increasingly dark and troubled, emotions amplified by Bowie’s agonised, raw vocal.

It’s a smart take and I buy it but don’t feel it. It’s hard to read specific emotions and motivations in the performances of a singer as mannered as Bowie, particularly at that time. His pain, confusion, and instability sound pretty much like Bowie’s default setting at the time.

After Gouster, Young Americans stands more strongly for me than it has before. As the album that follows Diamond Dogs and David Live, Young Americans came across as a half-thought-out pose with a handful of songs that signal how even when grasping at straws, Bowie had good musical instincts. After Gouster, you can hear Bowie intuiting his way toward something new. The Philly soul funk of Gouster develops some glam edges and rock impact. “Fame” is the pinnacle of that, and it points clearly to Station to Station—the masterpiece in this box set.

I’ve long heard Station to Station as Bowie realizing the limits of theatrical, persona-driven music, and the Thin White Duke was more of a wardrobe and haircut than a character. The fact that he shared much of that look including the cover art with Thomas Newton, his character in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth is telling. The movie’s title could have been an alternative one for this box set, but with Station to Station, Bowie had once again found a distinctive sound—one that, like Gouster and Young Americans, owed a debt to R&B, but not so much so that you couldn’t hear it without that context nudging you to notice how he doesn’t get the details right. It’s paired with robotic, metallic rock ’n’ roll impulses that sounds as modern now as it did then as it created an industrial, romantic backdrop for the expressions of Bowie’s fragmented mental landscape. The title cut remains rivetingly compelling, even though it has stayed enigmatic for 40 years, and the cabaret theatricality that led to Diamond Dogs is better realized on “Word on a Wing.” Nothing that made Bowie Bowie is denied, but on Station to Station he found new, contemporary, and personal ways to create a futuristic rock.

This one turned out to be more prescient than he may have realized. Who Can I Be Now? also includes a live recording from the Nassau Coliseum from 1976 with live versions of “Suffragette City” and “Panic in Detroit” that would have been the blueprints for all rock-disco hybrids if they had been released at the time. The recording would have sounded as at home in a dance club at the time as blasting out of a friend’s Camaro behind the high school during lunch hour.

One of the high points is a cover of The Velvet Underground’s “Waiting for the Man” that is so jaunty it almost mocks optimism. In a song that documents the degrading process of copping drugs, Bowie adds the lines, “No hills to steep / No mountain’s too tall / With love and faith / You can conquer them all.” It’s tempting to hear those lines as the expression of a guy who has stared down his demons and come out the other side, but Bowie never offered a narrative that pat or easy. Instead, the lines feel like the lies the song’s protagonist tells himself to deal with the situation.

Or maybe not. Maybe it’s just Bowie trusting the moment in a way that he hadn’t throughout the period covered by Who Can I Be Now? The set starts with his music at its most overdetermined, and when he realized he’d taken the character du jour as far as it would take him, he fished for a new way to make music. Who Can I Be Now? ends with the last great Bowie band album, and for those who love Bowie as a rock ’n’ roll guy, Station to Station is the end of the line. At the same time, Station to Station opened new doors for Bowie, and the next chapter—and next box set, I assume, with Low, “Heroes” and Lodger—is the most adventurous of his career, when Bowie the Artiste became Bowie the Artist.