The Gulf Restoration Network Modifies its Mission

The oil disaster of 2010 may be in the past, but the Gulf of Mexico still needs protectors.

The images were horrific: pelicans drenched with oil; pods of dolphins swimming under slicks of oily water; dead fish by the tons clumped together on the shoreline. But evidently nothing a minor league ballpark can’t fix.

Six years ago this April 20, the nation was horrified by the worst offshore oil spill in US history--the 2010 BP Disaster. BP would be fined $20.8 billion for its part in the spill, but it’s hard to decide on what was more infuriating--the actual damage (the lives of 11 men, more than 8,000 animals, and 16,000 miles of coastline affected by the upwards of 200 million gallons of crude oil that spilled into the Gulf for 87 days) or the company’s stoic, callous, defensive response.

Although it would seem like the BP money would go to making the Gulf and those affected by the spill whole again, state governments have had other ideas, some framed as “economic restoration:” Mississippi spent $15 million of BP’s funds to subsidize a new minor league baseball stadium, while Alabama used monies to repair the governor’s beach mansion, as well as cashing in on a $58 million beach lodge at a state park.

Today the media has moved on to the next outrage, and images of a hurting Gulf are so 2010, but the Gulf Restoration Network (GRN) hasn’t forgotten long-term effects: “Just because BP has settled and the monies have begun flowing to the Gulf doesn’t mean that all is well,” says GRN director Cynthia Sarthou.

“We still have a long way to go before the Gulf is restored to a pre-BP state--if that is even possible,” Sarthou says. The Gulf is hurting and coastal residents continue to struggle as well: many fishermen are suffering economic consequences due to reduced catches and there is concern that some shrimp stocks are still depressed. “Additionally, many members of coastal communities continue to suffer from health effects associated with the disaster.”

The GRN has been fighting for a healthy Gulf since 1995 and adapts to the needs of the Gulf and the public. In 2010, the GRN acted as first responders after the drilling disaster. It carried out the first aerial survey of the blowout, highlighting the inadequate responses from both BP and the Coast Guard. It advocated on behalf of those affected by the disaster by holding BP accountable for the Gulf’s cleanup, payment for damages, and insurance that this type of calamity never happens again. At one point that included filing a lawsuit against the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) when it neglected to promptly provide toxicity test results, ingredient lists of dispersants, and transparent investigation findings, among other demands.

Today, the Network works with like-minded groups from across the Gulf to closely monitor the ongoing restoration efforts. Together, they audit the BP settlement funds to ensure that the monies finance proactive environmental restoration, and that the economic development projects funded by BP dollars are not environmentally destructive. So far, some of the monies have been properly invested into recovering the Gulf’s health, including barrier island restoration, sea turtle habitat restoration and wetland restoration projects.

However, not all efforts are as sensible. GRN details that money is also slated to go to an aquarium in Mississippi, lodge and conference centers in Alabama, and a new home for the Biloxi Shuckers, a Double-A farm team for the Milwaukee Brewers. The GRN had to file suit in Alabama, when funds would have subsidized a beachfront hotel.

“In light of very real environmental issues, including stormwater and sewage pollution issues that these states have,” Sarthou says, “we feel that these ‘economic development’ projects will potentially make those problems worse.”

GRN hopes to improve the state of affairs by helping to shape policies and influence pro-Gulf health project selection. Currently, it is pushing for the RESTORE Council to reconsider some of its decisions. The Council is made up of five Gulf states and five federal agencies which have decision-making authority in the selection of these projects: “We are hoping that the RESTORE Council, who controls a pot of money that comes from BP’s water fines, will revisit their Comprehensive Plan to make it more robust and ensure that the best projects with the greatest beneficial impact are funded.”

In the Greater New Orleans area, Sarthou and her team work with local communities to try to make certain that BP’s monies flowing to the state for restoration help benefit local jobs. “BP monies must be applied to fix the natural resources that were damaged during the disaster and the communities that are dependent upon those resources for their economies and their culture,” Sarthou says. GRN has required that the projects funded with post-BP restoration funds train and hire local workers instead of bringing workers from the outside of the Gulf region to work on restoration.

According to the GRN, rebuilding and development has to be done with a careful eye to the the Gulf or it too could become a threat itself. Louisiana wetland erosion has been speeding up, and the post-Katrina reconstruction is bringing New Orleans a fresh, polished aesthetic but the GRN warns that all this new concrete is eco-destructive.

The non-porous concrete used in many of the projects can cause severe soil erosion and flooding, and the projects themselves have been hard on many of New Orleans’ historic oak trees, which are suffering from construction that can damage their root systems.

The Network says in light of all the construction, the best thing to do is to focus on bringing green back to the city and take care of what nature we already have.

In the greater New Orleans area, the rising sea levels and disappearing land are concerns, but they are manageable. According to Sarthou, the future is dependent on an active, strategic approach to the city and state’s ongoing relationship with the Gulf instead of piecemeal, reactionary actions. According to Sarthou, “The key to New Orleans resilience lies in the city’s implementation of a comprehensive approach to stormwater management, as well as other adaptation strategies.

The GRN is calling for progressive policies and infrastructure initiatives that support a more resilient stormwater management system for the city. The approach New Orleans is committed to is the 2013 Urban Water Plan, which tackles three main issues: flooding caused by heavy rainfall, subsidence caused by the pumping of stormwater, and wasted water assets.

As part of the their efforts to educate about innovative stormwater policies, GRN has co-founded the Greater New Orleans Water Collaborative, a diverse group of organizations and individuals working in New Orleans to advance comprehensive stormwater management which is guided by the vision of the Urban Water Plan.

Sarthou says the GRN is currently “working on more effectively engaging with and organizing vulnerable, low-income neighborhoods that currently bear the worst of the localized flooding in the GNO area on the causes of localized flooding, and subsidence [as well as] opportunities for communities to address the flooding problem(s) in their neighborhood.”

The Network encourages residents to stand up for their homes and their neighbors because far too little is still being done, and the long term effects will be multigenerational if meaningful intervention isn’t achieved soon. “There is a need for government bodies to coordinate to ensure that funds are used effectively to ensure that restoration has the greatest benefit for the Gulf ecosystem,” Sarthou says. “Communities are dependent upon these [natural resources] for their economies and their culture.”

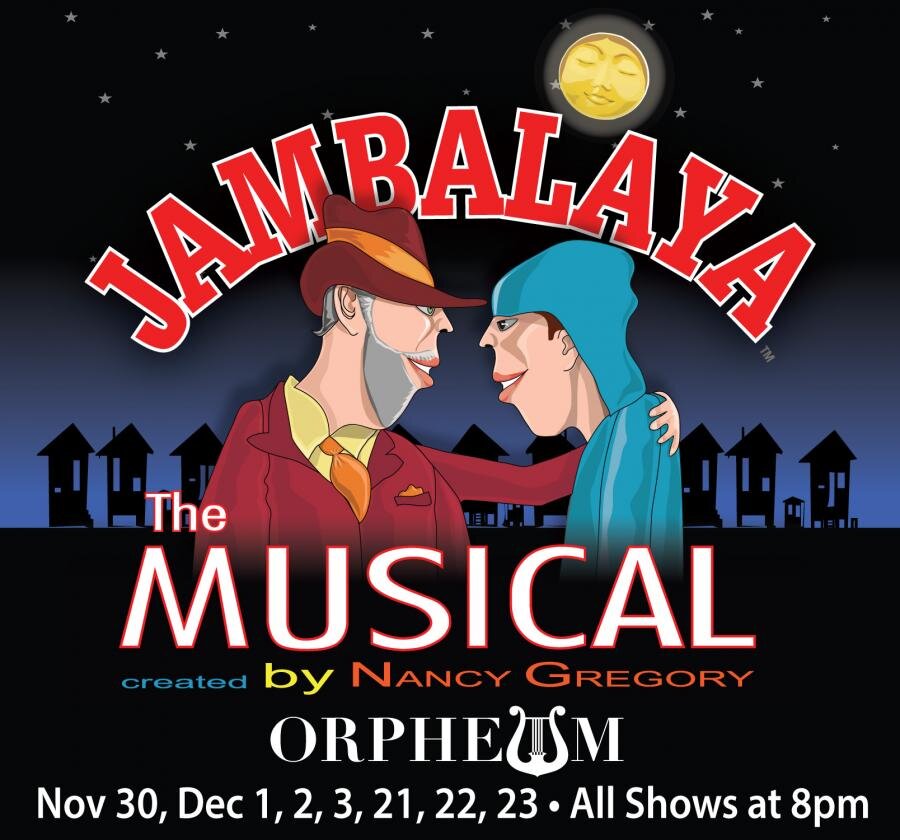

My Spilt Milk is pleased to partner with the Gulf Restoration Network for the My Spilt Milk Awards. Representatives will be on hand to talk about their work Thursday night at The Howlin' Wolf.