The Felice Brothers Sing the Praises of the Country Life

The folk band will play the Civic Saturday with Conor Oberst, but its members are happiest at home in the country.

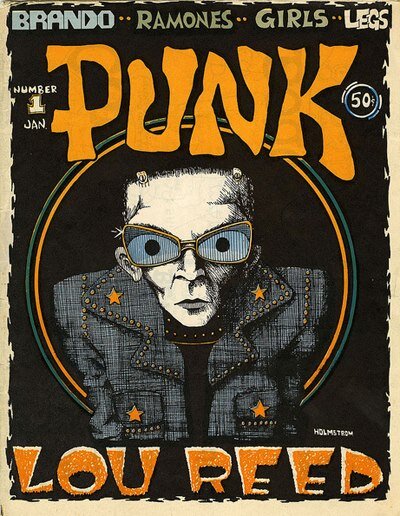

James Felice remembers how The Felice Brothers thought of themselves a decade ago when the band from Upstate New York went into New York to busk on subway platforms. “I think from the beginning we saw ourselves as more punk than folk,” he told Salon’s Scott Timberg. “Punk rock with more acoustic instruments.” In retrospect, Felice sees that attitude as a reflection of the band’s self-consciousness about the members’ limited chops, and the way the band offered listeners energy and intensity to compensate for the lack of precision.

“Folk is punk in its own special ways, and that was our attitude,” Felice says. “What Woody Guthrie would say: If you use more than two chords, you’re showing off. Just write a good song for people to enjoy. That was our attitude, and it still is in a way.”

The Felice Brothers will be busy Saturday night when they come to New Orleans. They’ll open for Conor Oberst at The Civic Theatre, then they’ll back him for his set. The band also appears on his new album, Salutations, which is a warm, full-band remake of his emotionally harrowing 2016 solo—almost demo-like—album, Ruminations. The Felice Brothers have been playing with Oberst for a while now. They met a decade ago and hit it off, and “Conor likes to play with different people a lot, so he hired us to be his band a few years ago,” Felice says. Musically, the adjustment to performing with someone outside of their band was fairly easy, but there were technical issues to sort out. “We’d never had to learn anybody’s songs,” he says, laughing. Since they played on Salutations when Oberst recorded the album, The Felice Brothers know the material and it’s more or less in their style. Still, there remain moments that require a little subtle communication. “I’ll be next to my brother and ask, Hey, what’s the chord that comes after this one?”

Now, the band’s punk country days are behind it. The Felice Brothers are still pretty specific and anti-stardom. They don’t busk anymore, nor do they all live on a farm together. The rural life still shapes them, though. James remains in Kingston, NY, and they recorded their most recent album, Life in the Dark, in a friend’s garage.

The members of The Felice Brothers all still live in the Hudson Valley, but they have girlfriends and wives and don’t feel the need for commune-style living like they once did. The first member left the farm four or five years ago, and the change was positive. “It’s good to have space,” Felice says. The time spent apart from each other leading more conventional lives was good for the band as it allowed them to develop in the way normal, healthy people to, and that in turn gave them new influences to bring to the band. “We’re all doing better in terms of our relationship to reality,” he says. “I like that.”

Felice lives a couple of hours from New York City, and he has lived in the same county since he was five or six. He understands how people live in cities, but for him, a more rural existence has been grounding. “It gives me space and it gives me community,” he says. “I know people. I walk into a store and I see friends.” At the same time, he likes his ability to walk out of his house and into the woods, where he can be completely alone. He has always been able to get away from people when he wanted to and has come to value the ability to isolate himself when he wants.

“I get woozy when I think about how many people are in New York City,” Felice says. “I think I’ll end up staying in Upstate New York for the rest of my life, and I’m totally happy with that. Thrilled by it, actually.”

These days, the band’s affection for a more rural existence works with their career. They have a name and a label, and they can put out their music and tour. When they were younger, more restless and less secure, they went to New York more frequently. “We spent a lot of time in Brooklyn and Manhattan trying to make a name for ourselves,” Felice says. At this point in the band’s life, those gestures aren’t as necessary or don’t pay off enough to make them worth the effort, and the band’s never truly off the grid if a member can connect to the Internet. “We don’t crave that lifestyle or need what the city has to offer,” Felice says. The financial pay-off for more time in New York or in cities isn’t great enough to tempt them to spend more time there. “Better to have a good life and to make good music.”

Felice recognizes the band’s preference is shaped in part by The Felice Brothers finding their level. They’re not a buzz band the way they were from 2008 to 2010. They’ve got an audience and sell records, and choices they make can cause a few more or less people to see them or buy their music, but for the most part, they have their audience.

“When you start, everybody tells you the sky’s the limit and you’re going to be rich and a rock star,” he says. “Then you realize, No, that’s not going to happen. We’ve chosen a different path—or maybe we were forced down that path. Who knows?—and yeah, our career has found its level. Not to say that we can’t go lower—!”

After he stops laughing, Felice continues. “We’ve been a band for 10 years, and we’re happy where we are. It would be nice to make more money and have more security, but that’s not the way the music industry is heading anyway.”

The Felice Brothers recorded 2014’s Favorite Waitress at Conor Oberst’s studio in Omaha, and as much as they enjoyed getting into a good studio with cool equipment and the ability to really control the sound of their music, the sessions for Life in the Dark felt more in line with the band, its values, and its personality. The band was left alone to work the music out and make decisions that were true to The Felice Brothers. They could spend their time the way they wanted to without consciousness of the clock or how they occupying other people’s time, and it helped them focus on what was really important.

“It definitely gives you the opportunity to do so many things better,” Felice says of the studio experience. “It’s like, Aw man, we have access to all these tools. We need to take advantage of this stuff. That can produce awesome things, but it can also distract you from what the song is trying to say.” Studios often have a roomful of guitars to help musicians get specific sounds, but Ian Felice has never needed or wanted more than the one he has. “He doesn’t like playing other guitars,” his brother John says. “Never has; probably never will. He says when his guitar breaks, he’s going to quit music.” While the other band members aren’t as single-minded, they’re on the same wavelength. Being in a studio with more cool instruments was nice, but “we’re not gear heads,” Felice says. “I like nice things, but I don’t—care. I appreciate a good microphone and really like clear sound. I appreciate what engineers do, and I love tape. But I also know you can make a really good record with an old computer and a cheap version of ProTools.”