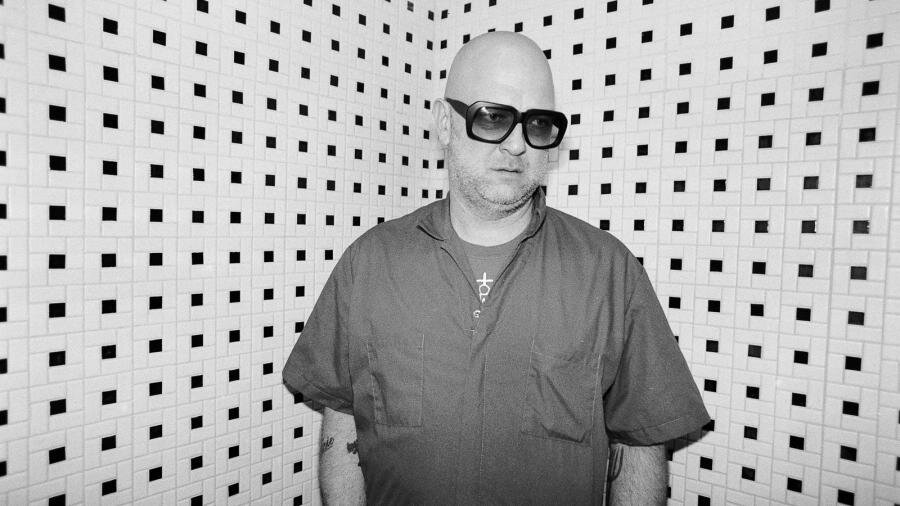

The Dap-Kings vs. The Retro Label

Sharon Jones told Rolling Stone that she's not retro, and Dap-King Gabe Roth agrees.

In today’s New Orleans Advocate, I wrote about Sharon Jones’ battle with cancer as part of my preview Sharon Jones and The Dap-Kings’ show Saturday night at the House of Blues. Dap-King and co-founder of Daptone Records Gabe Roth had more to say than fit in that story, particularly on the “retro” label, the Dap-Kings’ process, and vinyl. Here’s more from our conversation, which had a lot of laughs, even as Roth was making some points. This interview has been edited so that it is minimally redundant with the story in The Advocate.

I think most albums are too long, so I admire the relative brevity of Give the People What They Want (which is slightly more than 30 minutes long). How did you decide on the length?

Things like that should be questions of quality, not questions of quantity. We had 30 songs done for the record, but we hemmed and hawed and argued about it and voted on it and tried to come up with sequences that would flow. In the end, that’s what we came up that felt like These songs should be on the record; these songs should be on a different record. Or shouldn’t be out at all. There are some of those too.

The LP is the way we conceive of the whole thing. People who are listening to stuff digitally have their iPods on shuffle and they’re listening on their phone in the background. They’re not really paying attention to the album as it was created, as one piece of work. But I agree with you - there’s this expectation now for people to do 80-minute records when they don’t have 80 minutes’ worth of good music. They end up filling it with schlock and schtick and stuff. I don’t think you’re doing the consumer a favor by giving them more music. You’re only helping them out if you’re giving them better music.

My problem with long albums is that after a certain length, you can’t remember it all. Hum me the last two songs of an hour-long album - who can do that?

It’s hard because there’s a lot of pressure now from iTunes and Spotify and Amazon for bonus tracks and added value, but it’s a silly concept. “Added value” when you’re buying doughnuts is a baker’s dozen. You get that extra doughnut. But is it better to have more music? It’s a weird assumption: The more music you have, the better off you are. I don’t see how that follows.

How has it changed for you musically since you started playing together?

It’s changed a lot musically. Our influences have changed. Some of us have been playing together for 12, 15 years. The biggest change for me is the development of the band, the guys playing better and better. Everybody individually is creating a lot more.

Have you become better at writing for Sharon?

I’d like to think so, yeah. I’ve been for her for a long time so I know her real well. We know each others’ stories. She knows where I’m coming from and why I’m writing about something. I try to write about something that makes sense to her. Once in a while I or somebody else writes something that doesn’t make sense to her and she won’t sing it. Sometimes we explain it or see it in a different light; sometimes we drop it altogether.

One thing that struck me on the last two albums is that the songs are less reliant on the sound of soul and have more genuine drama.

When we started, we wanted to make funk 45s and make people dance. We are still in to getting people dancing. That’s a big part of the live show, but creatively as far as writing songs goes, a lot of us are trying to write real songs that aren’t necessarily dependent on the rhythm or the arrangement or Sharon carrying the feeling. There’s actually some chords and melody and there’s something to them. To me, those are the best songs. A song like “Wichita Lineman” - you could do that as a country song, as an R&B tune or a rock song and the story’s still there.

As far as the arrangements, that’s something that’s gotten a lot stronger too. Everybody’s a lot more conscious of what they should be doing and able to write for each other. There are a lot of songs on the new record where somebody brought in a piece of it or a hook or a riff and we put things together. The arrangements feel like they’ve matured a lot to me with a little more discipline and creativity.

We deal all the time with this pigeonholed, “retro” thing. We have a lot of different instinctual reactions to at this point, but at the end of it we’re trying to write original music. You can say Oh, it sounds like Motown or It feels like Stax, but those songs that we’re writing are new songs. It’s not like we’re saying, Shing-a-ling baby, let’s do the twist. We’re not just going through the motions, and we’re very conscious of that. I’ve been on sessions with other groups as a bass player or engineer and seen Grammy-winning records in studios in L.A., and it’s a different vibe than it is with our crew. They go in and play whatever bullshit, then come back to the control room and everybody pats each other on the back. That doesn’t happen at Daptone. We come back in there and everybody’s raw bordering on hateful: Don’t play that lick. That’s corny, or You nicked that from something. We’re our own hardest critics, but it’s a good process and a welcome process because it’s all people who respect each other and we’re all coming from the same place so it’s to a good end. We’re not always in agreement, but we’re in agreement that we’re doing our best to make the greatest record that we can.

If you listen to the songs on the records, even the most poppy ones like “Now I See” - Homer [Steinweiss] wrote “Now I See” and just the way the chords move in that song, there’s no other song like that. It has a shuffle that could have caught a couple of votes at Motown, but that’s not what the song is. There’s a real song there.

One of the things that’s frustrating to me is that we write songs about all kinds of different stuff, but no matter what you write, people assume it’s always about a jilted lover. They always assume that! You can write about having a bowl of cereal and the cereal for them’s a metaphor for love lost or something. Even “Retreat.” I read reviews: Sharon tells a would-be lover ….Where do they get that stuff? There’s no mention of love in that song. It’s a very personal song about Sharon and how relentless she can be for good or bad, but now people are interpreting it as her kicking cancer’s ass - which is a welcome perspective.

I don’t deny that our stuff has a real ‘60s feel to a lot of it, but we don’t approach it as archaeologists. It’s very live music, and everybody’s playing with a lot of heart and soul.

If you listen to punk music, rock music and what the latest college rock bands are doing - they’ve made a lot less strides since The Kinks then we have. They’re not that far outside the box. It’s just accepted that three-chord punk is not a retro thing. Or R&B - you go from Bobby Brown to Justin Timberlake. That’s 30 years; they should have gotten farther than that, don’t you think? Since drum machines, it hasn’t really changed that much. If you go back to the ’40s and listen to a record from the ’40s, then one from the late ‘40s, then one from the early ‘50s, then one from the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, and every couple of years you hear a very decisive change of direction. A change of sound, and that stopped happening. Once you get into the late ‘70s, it all slowed down into this weird, commercial quagmire of formulaic shit, so when you look at what we’re doing in that context, I think it’s a lot bolder for us to reject the way everybody’s been doing stuff for 30 years and take a raw, human-based approach. That may be similar to what was going on in the ‘60s, but it’s not based on that. It’s based on the same reasoning. It’s based on Hey, let’s go in the studio and make music together because that feels good to us. It’s not a question of What would Smokey Robinson have done?

I’d say we have more in common with punk rock things and singer/songwriter things than with most of the retro soul or neo-soul shit going on now because most of that stuff is so produced and corny, and what we do has a rawness or a realness to it. People ask why we have a lot of white college kids [at the shows]. How did this happen? The same reason that Seattle’s Sub Pop stuff got made. It’s reactionary. It’s people responding to raw feeling and being tired of the same, formulaic crap being shoved down their throats.

When you mentioned arrangements a few minutes ago, I thought of something as simple as the tympani in “Now I See” and how something so simple ramps up the drama in the song. It seems like on the last two albums you’ve tried to write songs to capitalize on Sharon’s ability to be dramatic.

That’s definitely true. The band’s tastes have changed over the years and we tend toward more dramatic stuff. Ten years ago, we were driving around in the van listening to The Isley Brothers. We still listen to The Isley Brothers, but we listen to more Delfonics now. That’s part of getting older too. You turn into a crotchety old man and want to hear ballads and deep songs. That’s part of it too. There’s always going to be people who like our first record the best and that’s cool. I’ve got no problem with that. And the reason the first record sounds like it does is that’s the record we wanted to make. That’s what we liked and what we wanted to sound like. It had nothing to do with what we expected people to buy. And we’ve held true to that. We make records that we love. To me, it wouldn’t be right now to go back and make a record of all funk grooves because that’s not what we’re feeling. It would be very affected.