"The Caped Crusade" Goes Behind Batman's Mask

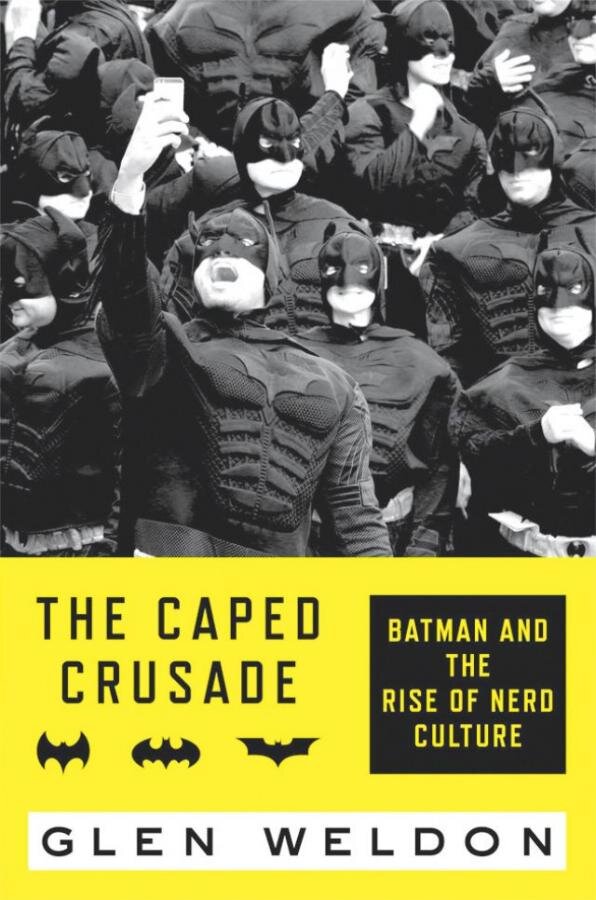

In the book, writer Glen Weldon tracks the changes Batman goes through in comics and beyond, and his relationship to the nerds who love him.

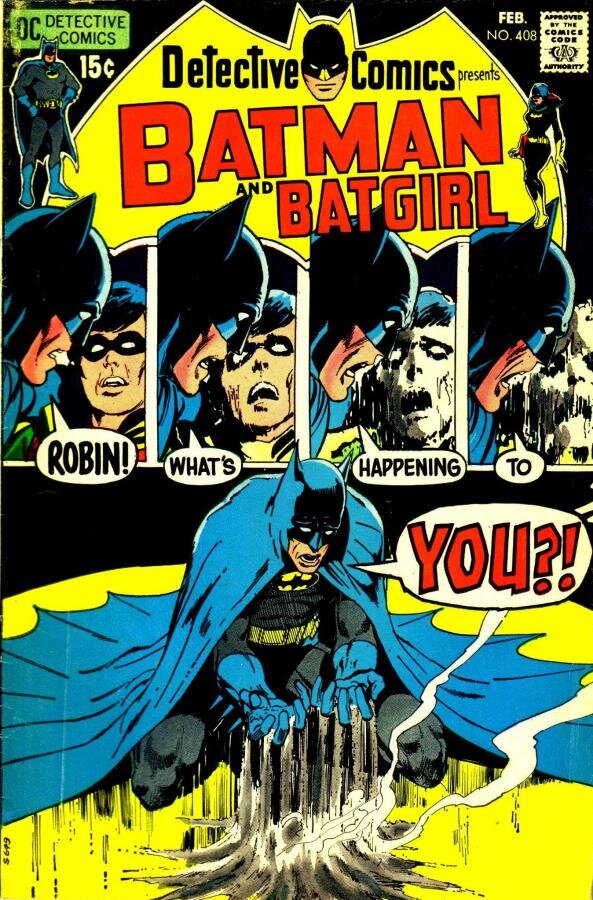

In The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture, Glen Weldon remembers his entry into Batman. It wasn’t the garish gun-wielding noir of the comic book’s early days nor the bonkers ‘60s with additions to the Batman family that included a Batcow, the sprite Batmite, and countless colorful Batsuits, each tailored for camouflage in another specific, improbable location. Weldon didn’t become a Batman guy during the character’s renaissance in the early 1970s or Frank Miller’s grim Dark Knight reinvention in the 1980s.

No, he became involved in the adventures of Batman at their least cool when played out on television by Adam West’s Batman and Burt Ward’s Robin, who battled a rogue’s gallery that would only years later answer unlikely questions on television game shows. Robin never broke off a “Holy What’s up with the whiteface makeup over the Joker’s mustache, Batman?” but we were all thinking it as the Dynamic Duo leapt from conveniently stacked crates in day-glo warehouses upon identically dressed henchmen who made the fatal mistake of standing together like bowling pins.

Weldon’s too young to have seen the show when it first aired in 1966, but because the show shot two episodes a week separated by a cliffhanger death trap, Batman went into syndication after only two years on the air, and Weldon saw the reruns. “They produced something like 128 episodes in just over two years’ time, which meant automatic syndication, and it would live on forever in syndication,” he says. “And because the show is so stylized and it has a look that turned up the volume on the ‘60s and made it more day-glo and pop art, it had a timeless appeal. You can look at it today and it still holds up. The suits are 1962 or 1966, but everything else about it has a timeless quality.”

In The Caped Crusade, the comics critic for NPR and regular panelist for its “Pop Culture Happy Hour” podcast tells in playfully witty terms the story of a character as it moves from the comics pages into the culture. As the character grew beyond the pages of comics, Batman developed two audiences—diehard fans that Weldon shorthands as “nerds,” and everybody else, who he dubs “normals.” The fans liked their Batman truer to the hard-boiled early days of the comic book, while others liked a lighter touch. Weldon has a foot in both camps. He self-identifies as a nerd in the book, but he tells a story in the book of attending a San Diego Comic Con and waiting in a line long enough to lead to food or water in less developed nations. In his case, it ended at a toy Batmobile.

“Batman was always my guy,” he says by phone. “He was the guy I played with in the backyard. I would take my parka and put it over my head and let the arms and actual coat of it dangle behind me. My friend would be Robin, and we’d run around the backyard quoting the reruns of the Batman 1966 television series, not understanding a word of it. Like many kids my age, that was my first exposure to superheroes in general and Batman in particular.”

Weldon didn’t start reading the comic book until 1977 at a time when Joker was more Heath Ledger and less Cesar Romero, more psycho than prankster. “There was a sharp disconnect between the Batman that was being purported on the airwaves and the one on Super Friends, and the one in the comics. That’s fascinating to me and something I wanted to write about.”

Weldon doesn’t assert that the TV Batman is the Batman. Instead, the story he tells is how his characterization has ping ponged between The Caped Crusader and The Dark Knight—the guy who’d dance the Batusi and the one who’d lead a vigilante army. The nerds Weldon references in the book’s subtitle continually advocate for the grimmer, grittier Batman, and the “rise” that he spoke of wasn’t so much the birth of nerds as evidence of their power. They want their Batman badass, and anything else—particularly the Joel Schumacher entries in the Batman filmography is heresy and meritorious of a sound mocking or worse. Their Batman doesn’t need superfluous nipples built into his costume; he has an oath.

“I swear by the spirits of my parents to avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals, ” a young Bruce Wayne intones over the bodies of his slain parents, but it motivated early issues of the comic. When writer Denny O’Neil tried to course-correct the comic in 1969 and get out of the zany shadow that TV show cast, he returned to that oath.

“Denny O’Neil’s genius was that he went back to the very beginning, saw that one panel where he is swearing the oath,” Weldon says. O’Neil’s run as a writer on Batman starting in 1969 posted the benchmark against which the character was measured for decades to come, and he centered his conception of the character on the oath. “An unrealistic, child-like oath, but that’s the power of that oath. And he said, This is what this character is going to be all about. He’s going to be obsessed; he’s going to be driven.”

That oath pointed to the dark, brooding loner—a spaghetti Western “Clint Eastwood in Bat ears” according to Weldon—that was at odds with the more genial tone of other comics and other iterations of Batman in cartoons and merchandising. His Batman is the more resonant, gripping Batman, but holding that line proved challenging. In the late ’70s, Weldon writes, “Unconsciously or not, these younger creators steadily infused the new, darker Batman with the whimsical tone of the fifties and early sixties Batman—the comics they’d grown up on.” The Caped Crusade shows how that pendulum swing characterizes the history of Batman.

That oath is central to Batman, but Weldon cautions not to overlook billionaire Bruce Wayne’s wealth, even though readers have to do some intellectual stretching to make that connection.

“When I would talk to fans—and I talked to hundreds—not a single one of them would say ‘Wealth. That’s what makes Batman Batman,’” he says. “They do not see it as part of the character even though it makes all things possible. It works like magic in any given Batman story. It makes everything possible. They would say, ‘Oh, that’s a plot point. That’s not what makes him who he is,’ and that’s such an American idea—that we can all grow up to be billionaires if we just try hard. There’s also something else about Batman. Because he’s non-powered, everybody thinks that they could be Batman. They’re just a couple of sit-ups away and they could be who he is.”

The intriguing tension in The Caped Crusade comes from Weldon’s effort to treat Batman as a genuine character as he passes from one set of corporate hands to the next. DC has a bible that effectively enforces a measure of uniformity across time and the breadth of Batman comics, but DC Comics’ efforts to create a more orderly DC Universe has wiped out hundreds of issues of canonical backstory and scrubbed whole chapters of Batman’s history out of existence more than once. That means the bible has been redacted a few times, and as different writers focus on different aspects of Batman’s story, characterization changes. He’s your dad. He’s emo. He’s pedantic. He’s tight-lipped. When he’d show up in team books such as the Justice League of America, his dialogue—to be fair, like almost every character in the book—had so little personality that the voice balloons could be rerouted without doing much damage to the story. Add to that Frank Miller’s Dark Knight stories and the Batmen of the movies and it’s tempting to think of all these incarnations of Batman as different characters that share an origin story, a wardrobe and little else.

Weldon contends that one of the most successful treatments of the character is Batman: The Animated Series, which returned in tone and style to the early 1940s. Another came from Scottish writer Grant Morrison, whose seven-year tenure writing the character attempted to resolve the variety of characterizations and contradictory storylines by positing that they all were true. The 1939 Batman with a pistol and the late ‘50s Batman with a white polar Batsuit and the ’66 Batman who fought Roddy McDowell as The Bookworm and Victor Buono as King Tut, and the ‘70s obsessive Batman written by O’Neil—all of it. The run is dizzying at times and meta- as a matter of course, but it’s also comes close enough to pulling off its premise that Morrison earns a little slack at times.

“I like the ambition of Morrison’s run when he settles down to tell a story instead of running off to be as trippy as possible,” Weldon says. “I think he’s got a really good handle on the character. I really liked his run on JLA because that’s when Batman becomes the tactician. It has always been in there, but he brought it to the fore.”

Then, after Morrison finished with Batman in 2013, DC did more housekeeping and swept most of what he’d done out of the canon.

Much of the fun of of The Caped Crusade comes from Weldon’s account of the nerds’ assault on Hollywood and its market-driven, focus group-tweaked treatment of Batman. Adam West’s Batman was the bête noire for fans of long-time fans of the comic book, and they saw Michael Keaton, Val Kilmer, and George Clooney as too West-like for comfort. “Hiring Mr. Mom to portray the Dark Knight was seen as proof that what Hollywood wanted was to take the character not, as it had promised, back to his 1939 roots but back to his 1966 leaf rot,” Weldon wrote.

The hardcore fans’ desires didn’t change over the years, but the ways to make them known did. People who once vented by writing letters to the comic met online in forums to express their all-capped, exclamation point-fueled rage by 1995’s release of the first of Joel Schumacher’s Batman Forever. In 1997, online comics news sites published brutal advance reviews of Batman and Robin, and a now-defunct website was launched solely devoted to Schumacher anger: BringMeTheHeadOfJoelSchumacher.com. By the 2011, cell phone technology had developed to a point where fans were able to post surreptitious photos from the shoot in the streets of Pittsburgh of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises. Since Nolan’s Batman was their Batman, fans were on board, so much so that they used their technological prowess to join Nolan rather than fight him. Quickly, there emerged volumes of Batman fan fiction based in Nolan’s universe.

The connection between Batman and nerds seems natural to Weldon. “Batman’s the ultimate nerd if you think about,” he says. “He keeps a lot of toys in basement and doesn’t get a long well with others. He’s really good with computers.

“I think that a character like Batman speaks to the specific kind of masculinity that a kid who spent much of his teenage years being shoved into lockers can imagine. He likes to picture himself as a brooding, laconic, super-jacked, super-muscled guy. Nerds maintain that they don’t, but what they desperately want is for the popular girl in school to love them, they want to be friends with the jocks. They want the acceptance of the mainstream, but once they get it, they—and by ‘they’ I mean ‘we.’ I mean ‘I’—have no idea what the hell to do with it.”

Weldon is more circumspect in conversation than in the book about the word “nerd” itself. He clearly considers himself one and embraces it at a time when more and more people describe themselves as nerds for one thing or another. Foodies, he contends, occupy a point on the nerd scale because its defining characteristic is not what they love; it’s active, immersive way they love. Still, a conversation with a niece told him that the word might not be as reclaimed as anyone years out of high school might like to think. “The word ‘nerd’ is still a hurtful one,” Weldon says. “It’s something that the group decides. The group assigns your identity as a nerd.”

Weldon’s first comic was an issue of Superboy and the Legion of Superheroes and while comics connected, it specifically didn’t. Too talky. Too much politics as they had to elect a leader. He remembers buy an issue of Amazing Spider-Man early on, but a Weldon continued to buy comics, he realized he was a DC guy. “I embraced the black and white,” he says. “I embraced superheroes that didn’t fight with each other. I thought they should be on the same side and should all be chums.”

Over time, Marvel Comics’ ideas about characters and characterization became the industry norm with every superhero in need of a little therapy and every story coming with a side of soap opera. In general, that was for the best as it strengthened the characterization and made comic book stories more engaging, but it made the wacky Silver Age DC comics seem like they came not just from another time but an alternate universe. While researching The Caped Crusade, Weldon got revisit the thing that he loved about comics in the first place.

“One of the pleasures of working on this book was going back to the archives and reading Space Batman and Zebra Batman and Turning Into a Genie Batman,” he says. “That stuff is so raw, unfettered imagination. Just churning out stories to try to grab the attention of eight-year-old kids. That means things that we value now like nuanced characterization and dialogue goes out the window in favor of ideas. Great, big, huge, crazy ideas.”