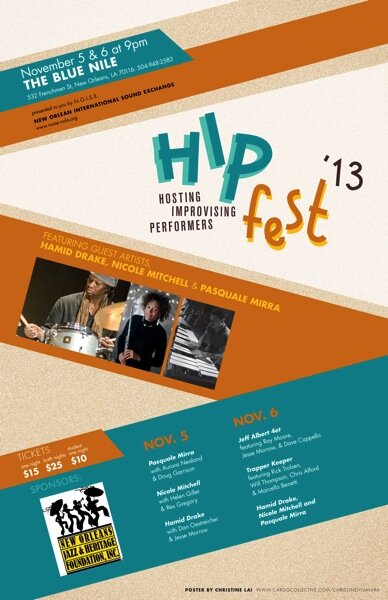

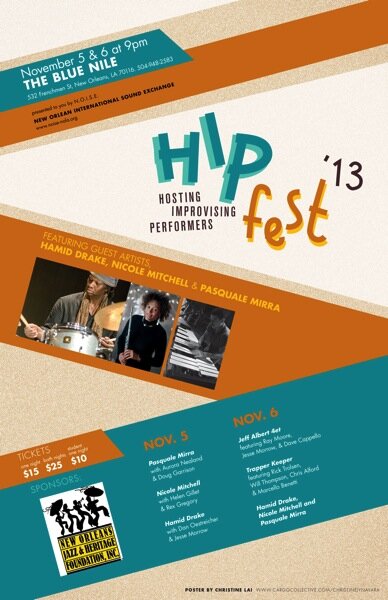

Shooting from the HIP

"Improvisation" is a human word tonight and Wednesday night at HIP Fest.

HIP Fest was the brain child of New Orleans-based drummer Marcello Benetti. He felt that thecity's improvised music community was in a particularly good place right now, and that not enough people knew it. The festival takes place tonight and Wednesday night at the Blue Nile, and “HIP” is short for “Hosting Improvising Performers.” The festival will bring together locals including Benetti, Aurora Nealand, Rick Trolsen, and Doug Garrison, who play host to three international improvisers - drummer Hamid Drake, flautist Nicole Mitchell, and vibraphone player Pasquale Mirra. Drake is one of the biggest stars in the improvised community today and a regular visitor to New Orleans, where he has performed and recorded with Kidd Jordan and Rob Wagner. Mitchell has won Downbeat’s Best Flautist recognition three years in a row, and the Italian Mirra will visit the United States for only the second time to be a part of the festival. Before this, he had only been to New York, where he played the Vision Festival with Hamid Drake.

“People here don’t know Pasquale, but in Europe he’s a rising star,” trombone player Jeff Albert says. Albert, Benetti, Helen Gillet and Will Thompson have gathered for coffee on a patio to talk about the improvised music community. The city has developed a substantial and distinctive one, one less bound by theory and shaped by the experiences the players have on other, non-improvised gigs, or encountering social music such as brass bands. Musical hierarchies seem foolish here, so some of the brainy tendencies of other improvised communities don’t fly here.

What does is the understanding that the music is more than just music. It’s simultaneously personal and social, and the four have a dense network of musical relationships, having played together in more combinations than they can count. Add the musicians who aren’t at the table and a chart of who has played with who could easily an airline route map found in the back of a in-flight magazine. Albert remembers that the first time he shared a stage with Gillet was a contemporary classical music concert. “You were my teacher too,” Thompson says, remembering a class at University of New Orleans.

“This community is very sociable,” Gillet says, “If you hear that somebody has some big ears and can really listen, or plays an instrument you’re really feeling at the time, that’s who you’re going to call.”

Improvised music is exactly what it says it is - music spontaneously composed in performance by the musicians. Many of the performers have jazz backgrounds, but not all of them, and the freedom from jazz conventions gives improvisers more choice of who they wish to play with. A traditional or contemporary jazz band will choose certain instruments to play certain parts. If you don’t have parts, “it lets you select people instead of instruments,” Albert says.

“In jazz, your personality is very important besides skill,” Benetti says. “When you go to improvised music, it’s even more. I need that personalty. It happens that he’s a pianist.” That makes the music about the performers first, and the players learn about each other as they play. “It’s a conversation for sure,” Thompson says.

As the musicians start to talk, it becomes clear that improvised music and its demands on the individual force a degree of introspection and self-examination. None of them started on the path to play improvised music, but none of them ended there by default. “I remember getting out of Loyola with a Bachelor’s Degree in Jazz Trombone and being mad that I didn’t sound like J.J. Johnson,” Albert says. “I later realized that I didn’t do what I had to do to sound like J.J. Johnson, but, at an improv class one time, Tony Dagradi turned out all the lights and said, We’re going to play for 20 minutes. No preconceptions. I’m going to start playing, and play. It was a religious experience for me. Since then, whenever I’ve been in more freely improvised situations, that’s when I’ve felt the most successful and got the best response. That’s what a lot of this is about - a way to find your personal, true music.”

Benetti had a similar experience in Bologna when a friend and sax player invited him to bring his drums over to play together in the garage. Benetti’s musical experience to that point was in jazz, so when they got together he was confused when the sax player wouldn’t call a tune, instead saying, Let’s play.Benetti started a swing groove, but his friend cut in. Marcello - play. “Four or five times this happened,” Benetti says. “ He says, Marcello - play. Feel free. For a minute, that happened, and he started screaming, That’s it! Man, I was feeling in my stomach like it was one of the best things to happen to me. I flew for a minute.

“I said, ‘Man, that’s amazing.’ He put his hand on my shoulder and said, You know there’s no way back.”

Those stories prompted Gillet to tell her conversion experience. She was trained to play classical music as a cellist, and someone suggested that she take a lesson from an Indian classical cello player in Madison, Wisconsin. Rather than talk about technique or anything Gillet expected, the woman sang her a simple Indian melody and asked her to play it. “I found the first note, thank god, and I thought the next was a third,” she remembers. “I’m 19, and she said, Yes, those are the notes, but that’s not what I sang.” It took her more than a half-hour to catch all the nuances of her voice singing the phrase. “As I was driving home, I had that same feeling of What is this musical world that I had no idea existed, where I was just using my ears and reacting to the sounds coming in -”

“- Where it was about shapes and textures and feelings, and not about That F-sharp was a little high,” Albert says.

“And sincere and honest reactions to sounds coming into your ears, and what conversations you want to have with them,” Gillet says.

But the experience isn’t only a Matrix-like revelation of another world. In the case of Will Thompson, he started there when he first touched the piano. “I just started playing,” he says. “I didn’t have a lesson until I was in junior high. The concept of written music seemed really foreign, and it still does in a way.” He went on to get a Masters Degree in Jazz Performance, which surprised him considering his starting place.

In each case, the experience led them to question many of the preconceptions that surround music. If people pick up instruments to express themselves, why the focus in musical education of learning to play other people’s music? Is the way you play your instrument the only way to play it? Does it offer up other possibilities for making sounds? Gillet’s mother asked her after a gig in Chicago, “Helen, what is that sound you make that sounds like butterfly farts?”

“The key is to make those sounds with some sort of semantic content instead of making those sounds because you can make those sounds,” Albert adds. “The difference between music and people who make weird sounds is, does it mean something?”

The musicians at the table use the word “conversation” to describe the way they play with others, which underscores the social dimension of the music. How they feel about performing with someone affects how they feel about that person. Enjoy the interaction; enjoy them. Play with them much and you know them. “I look forward to meeting improvisers because there’s something about the process of becoming an improviser and staying an improviser that takes a journey through what’s important to you as a human,” Gillet says. The HIP Festival was conceived with those conversations in mind. “I’m sure that somebody on this festival will end up working with one of these people in the future,” Albert says. “And it’s going to be because we had a really great hang together back stage and want to play together.”

Improvised music is often caricatured as noisy or willfully eccentric, and it can’t be denied that it has that tradition. Questions about how to play an instrument inevitably lead to questions about what qualifies as an instrument. In the course of our conversation, Gillet mentioned a pianist who slowly deconstructed what it means to play the piano until he was playing a bicycle outfitted with springs and pickups. The players at the table contend that that image came from somewhere, but it by no means defines what most players do. Drake, Mitchell and Mirra all come from the melodic side of improvisation, and the music they and other improvisers make is “very honest people music,” Albert says. “This idea that what we do is difficult to parse or requires deep intellectual knowledge - I don’t think that’s valid. I think you can to it completely inexperienced with an open mind and get what it’s about right away. Because it’s about interaction between people.”