Seratones Remake Themselves for "Power"

The Shreveport rock band plays One Eyed Jacks Saturday night, and it has traded some of its Detroit snarl for southern soul.

“What are we about? Who are we?”

AJ Haynes and Shreveport’s Seratones asked themselves those questions after they parted ways with guitarist Connor Davis in 2018. He had been part of the band along with bassist Adam Davis and drummer Jesse Gabriel from the start, and his furious guitar was crucial to the band’s MC5/Detroit rock ’n’ roll sound on display on the band’s its 2016 debut album, Get Gone. But when Allison Hussey reviewed the album for Pitchfork, she wrote that Haynes was the best thing about the band. “Haynes' charisma is palpable through almost every song—even the giggles that bubble up on ‘Kingdom Come’ inject the record with a genuine joy,” she wrote. “She ends that song with the line, ‘I’ll be your best, believe me,’ delivering the last two words like a slow punch to the gut. She does so much work on Get Gone that you wind up hoping she follows through on her promise.”

Power, the band’s second album from earlier this summer, is the album Hussey asked for, and Seratones with new guitarist Travis Stewart (guitar) and keyboard player Tyran Coker play One Eyed Jacks on Saturday night.

Seratones started in 2013, and the members more or less fell together in Shreveport’s indie music community, united more by the D.I.Y. spaces they inhabited than musical affinities. “We had everything from thrash to psychedelic to surf rock. Stooges-esque I-IV-V punk,” Haynes said of their musical influences in 2016. She also had a background in the church.

Get Gone came out on Fat Possum Records and got some strong reviews. Record Collector wrote, “A new star has been born and this time comes reinforced by a shit-hot band,” and Mark Deming wrote for AllMusic.com, “They've made an album that rocks hard but with plenty of real-deal soul.”

“That record was raw power,” Haynes says now. “It was, Let’s see what we can get away with, Let’s see how much we can fit in. It was this explosive thing that was predicated on first thought, best thought.” She enjoyed the album and the sense of spectacle that produced it, but the soul that critics heard in her voice was a product of her pipes and not the words themselves. The lyrics were the kind of lyrics that garage punk had. The words to “Necromancer,” for instance, were more about energy than meaning. She sang:

BABY!

You got a wicked design

For your double trouble, and I'll be boiling away

BABY!

And on your radio feed

I'm just a ticking, ticking, and darling, you've got it made was a satisfying

As much as Haynes enjoyed that, Seratonesonly scratched some of her creative itches. She and bassist Adam Davis had collaborated on absurdist art installations as well, and she had bigger thoughts than the band could easily accommodate.

In conversation, Haynes isn’t exactly all business, but she stays focused. She doesn’t care for drama, she says, “because I ain’t got time!” She’s pragmatic—“I’m an incredibly, deeply, almost too pragmatic a person” she explains—which translates in an interview to a very engaged, focused conversation. She’s soft-ish spoken, has fun and goes where the conversation goes, but her mind doesn’t wander, nor does she veer off in unpredictable directions. The one time she rambles, she apologizes and explains that the coffee’s kicking in. She jokes, but she remembers why she’s on the phone.

“I’m interested in the artist as part of a greater cultural conversation,” she says, but she wasn’t sure how to get ideas along those lines into band conversations. Seratones weren’t unfriendly to open, personal conversations, but as the only woman in a band full of guys, getting her issues on the table wasn’t easy. “I couldn’t speak freely in the band,” she says, but not necessarily because others didn’t want to hear it. She didn’t want to make anyone uncomfortable she says, and it didn’t help that she had yet to work out ways to talk about the things she wanted to talk about. “I didn’t want to be vulnerable.”

Haynes says she learned to become a better bandmate when she learned to become a better songwriter. She started scheduling songwriting sessions and while in the room with other writers, she realized that she needed to learn to talk more about herself. Without that, she had no value proposition and would contribute ideas that anyone could contribute. The introspection wasn’t the hard part, though. She could do that. “It’s scary to talk about yourself in a way that doesn’t sound narcissistic and sounds honest and talks about your real experiences,” she says. Once Haynes figured out how to be honest, she became a better communicator with the band.

In 2017, Seratones parted ways with Fat Possum before eventually moving to New West, then they split with Davis a year later. “We grew away from each other,” she says diplomatically. “We wanted different things.” Haynes doesn’t duck the questions, but she doesn’t elaborate either. “I couldn’t have asked for a better split,” she continues without adding any details. She just says the relationship wasn’t working anymore, so it made sense to quit it.

The split sounds like an extension of Haynes’ growth into her role as a front person, but she doesn’t say that. When she began as the band’s singer, she had to learn how to be its front person and its singer. From church, she knew how to sing, and she knew how to get and hold the audience’s attention. She had also experienced the value and the limitation of the first thought/best thought aesthetic and knew that she wanted to move in a more deliberate direction. She could create rock ’n’ roll heat singing garage band lyrics, and could do it well enough to simulate soul. What could she do if the words actually meant something to her? If they reflected real hopes and fears?

That kind of introspection was only the start of the process that led to Power. Haynes thought about the space she occupied as a singer and didn’t stop there. “What is the space of the bassist? What is the space of the drummer?” That led to conversations about the follow-up to Get Gone so that it would be less impulsive, and she feels like they succeeded. “It’s everybody in service of the song instead of a borderline-masturbatory Look what I can do!” she says.

Part of the reevaluation process meant recognizing some of the baggage she brought to the project. “I’m a bit of a catastrophist,” Haynes admits, and she had to come to grips with the possibility that disaster wasn’t always mere moments away, and that she deserved good things. It meant thinking about what constituted success. Am I well paid? Am I cultivating happy relationships? Am I making good songs? Cool—that’s success. How do we grow from there?

As an artist, she had to think about how she was using her platform. She had to embrace the reality that as an artist, she could talk about race, gender, and power in ways that people in other jobs couldn’t, and that made it more important that she did so. And she didn’t want to live in a genre jail, limited by one sound. “I wanted to make a record that I wanted to listen to, like a good playlist,” Haynes says, and Rick James and Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall were part of the band’s listening regimen before the sessions started.

“A playlist isn’t all one thing, but there’s a thread or there’s a theme that ties it all together.” She hears soul as that thread, but as an ethos and not a series of genre characteristics. There are multiple diasporas,” Haynes says. “There’s a diaspora from West Africa, then there’s this diaspora from the South, and then there’s also this smaller diaspora from the church, the nucleus of black culture. When you can’t find church in church, you find it in something more honest to your unique situation. It’s that honesty to your unique situation that makes soul music interesting and relatable.”

The idea of being relatable returned Haynes to the importance of communicating from a more personal space, which meant making herself vulnerable. The song “Crossfire” on Power embodies vulnerability as Haynes, accompanied only by a piano, sings:

Save a little lovin' at the end of the day

I'll be strong for you, in a song for you

Caught up in the middle when the crossfire fades

I'll hold on for you, just hold on to me

The ballad calls for us to hang on to each other in hard times, but for Haynes, the crossfire was literal. She wrote about gun violence from a place of being terrified. She wrote it on her own but didn’t plan to put the song on the record. The rest of the band and producers Chris Sunday and Cage the Elephant’s Matt Schultz lobbied her to include it until she realized that the song was proof of her concept. Oh shit, this is going to work.

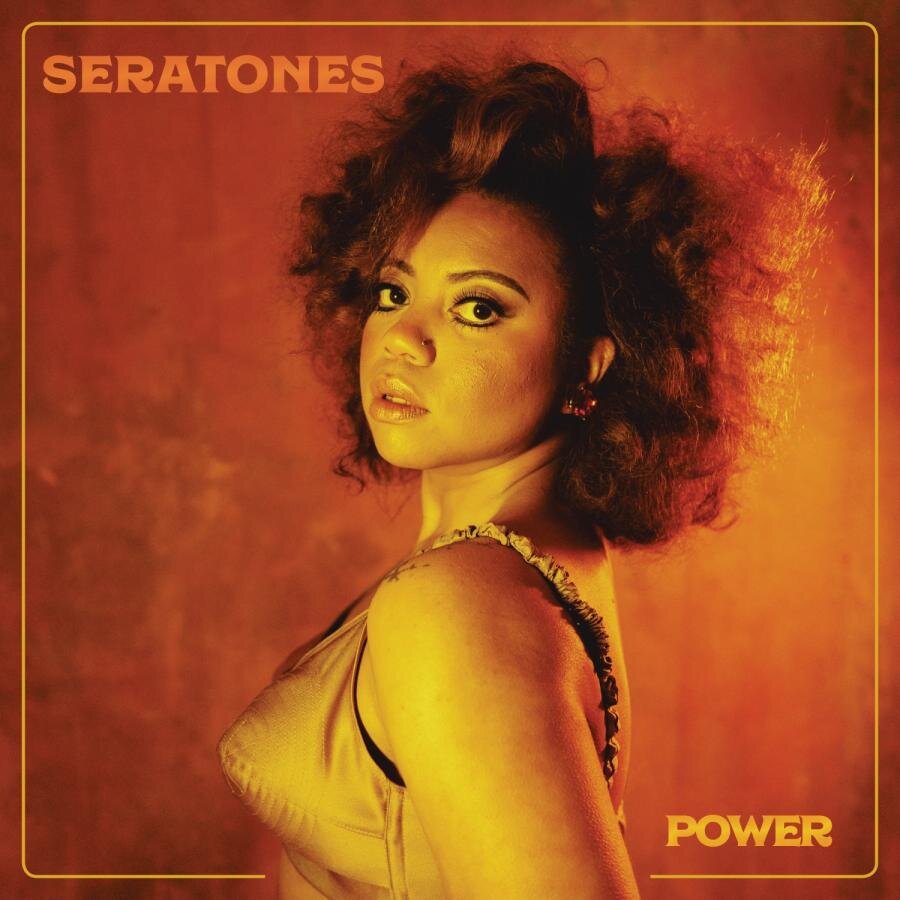

“Crossfire” is about finding a source of strength while in fear, and it fits into the exploration of power that gave the album its title and animating concept. That principle shaped other decisions including the album art, which presents Haynes wearing only a bra. “Power comes in vulnerability,” she says, “and what’s more vulnerable that being naked on the cover?” She had to have the bullet bra specially designed because in the 1940s and ’50s when they were made, they weren’t made to match black women’s skin tones, coming only in peach, ivory, and black. “What kind of erasure is that?” she says, laughing, as it was clear that manufacturers didn’t acknowledge black skin or imagine black women wearing their products.

“Crossfire” and many of the songs on Power work in the same way as classic soul, speaking first to their moment but in a language that will outlast the contexts in which they were written. The cover art evokes World War II-era pinups, inserting Haynes into a past that Donald Trump doesn’t have in mind when he talks about making America great again.

“The current administration is toying around with the idea of a mythic past,” she says. “An erasure of certain people’s history, and erasure of certain people. Toni Morrison said—I don’t know if I have this quote right—‘I don’t have time for art for art’s sake,’ and I feel that too. There was a time when I did but that time is not now. The most powerful way to undermine abuses of power from fascists is art. The Third Reich—they worked so diligently to try to suppress art because they knew it was the most powerful weapon. It makes people question; it makes people have to learn empathy.”

But as easily as Haynes can place Power in the culture wars, she can telescope back to the stories that inspired the songs. “I can tell you where every moment in every song came from. Who was I listening to? What was I reading? Who said these words? I think too often artists don’t give credit where it’s due. You’ve got to pay homage, you know?”

Note: Actually, Toni Morrison said, “All of that art-for-art’s-sake stuff is BS.” What's not BS is our review of Power, published last month. We first interviewed Haynes about Seratones in 2016.