Searching for Clifton Chenier

Todd Mouton discovered why no one had written a biography of the zydeco pioneer when he began working on his book "Way Down in Louisiana."

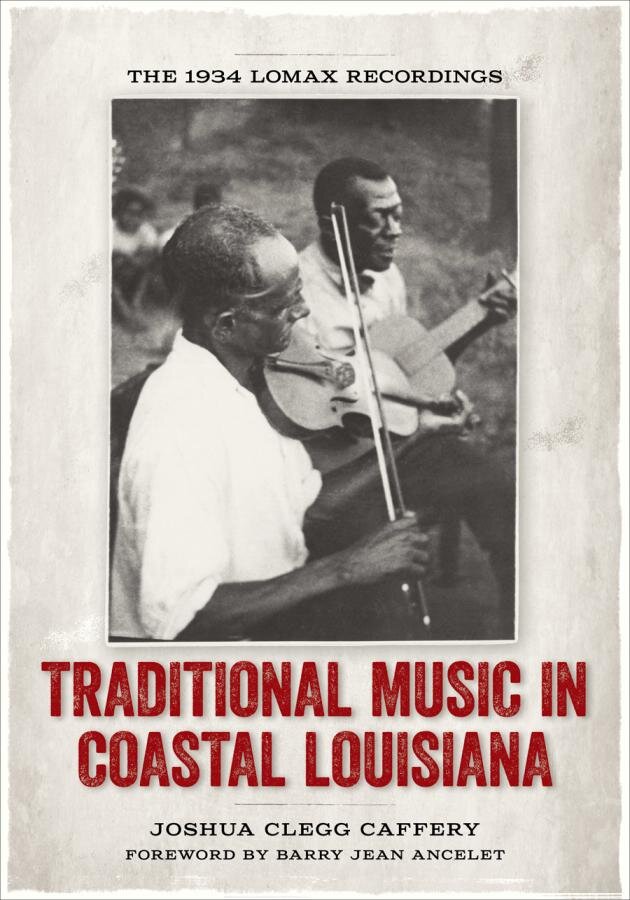

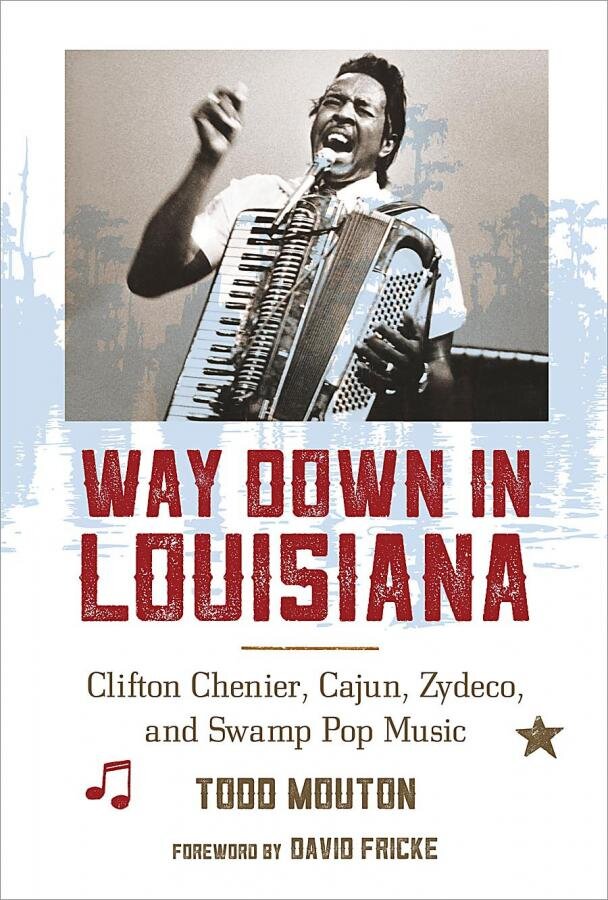

The structure of Todd Mouton’s book Way Down in Louisiana tells you what you need to know. The book is subtitled “Clifton Chenier, Cajun, Zydeco, and Swamp Pop Music,” and if you look at the book from the side you see a thick series of red pages in the middle. That is Mouton’s biography of Clifton Chenier, and as the rest of the book shows, Chenier is at the heart of music from South Louisiana, just as he is at the heart of the book. The artists whose stories surround Chenier’s—Buckwheat Zydeco, Lil’ Buck Sinegal, Lil’ Band o’ Gold, and more—don’t all connect directly to him, but none of them would exist without him.

Mouton will sign copies of Way Down in Louisiana at Octavia Books tonight at 6 p.m., and for him the book is the culmination of a long process. He spent a lot of 1995 and 1996 working on it and thought he’d have it done much sooner. Writing about Chenier seemed like a no-brainer, but once Mouton began to work on the project, he realized why no one had written a Chenier biography any sooner. As important as the zydeco pioneer was, Mouton found surprisingly little documentation of his life. He’s not certain if Chenier was literate, but he certainly didn’t leave behind any writings of his own unlike another Louisiana musical icon, Louis Armstrong. Chenier was only interviewed four times, and his music has been repackaged enough times that even albums don’t tell a reliable story. It wasn’t until late in the writing process that Mouton found a video of any length of Chenier in concert in Baton Rouge in 1977.

“For a while the trail seemed kinda cold,” he says. “Maybe it wasn’t supposed to happen until now.”

In 2003 he realized that if he combined what started as a Chenier biography with other articles he had written about contemporary Cajun and zydeco musical acts, he could tell a larger story with cross-chapter connections. It wasn’t until May of 2014 that he knew his ending. That month, he went out on road with Roddie Romero and the Hub City Allstars, who were touring with Los Lobos. “Boom—all this crazy stuff happened,” Mouton said, and time with both bands led him to think about the role of food in music culture. As fruitful as that experience was, he still had the nagging sense that he didn’t have his ending.

In December 2014, he saw The Magnolia Sisters share a bill with Bonsoir, Catin in Lafayette on the night that the Grammy nominations were announced. Both acts discovered that night that they were up against each other for the Best Regional Roots Music Album. “The stories just presented themselves,” Mouton realized. “Suddenly, I had this three-part thing—this musical biography of Clifton, these other artists like Buckwheat and Zachary Richard and Beausoleil and Lil’ Buck and Steve Riley who interconnect in different ways, and then this ending on Roddie Romero and Bonsoir, Catin and Los Lobos. It all comes back around in different chapters.”

Because of the gaps in documentation, Mouton had to rely on the memories of those who played with Chenier and saw him. That gave him a good idea as to what happened, but those accounts didn’t give him the sort of psychological insight that made it possible to really understand Chewier or recreate his voice. That limits the insight that Way Down in Louisiana provides into Chenier the man, but this challenge created a rare dynamic. Biographies can be hard on legends as their subjects become real, but Mouton studied Chenier and told his story without spoiling his mystique. Mouton can talk about what Chenier did, but not necessarily why. “What was driving that guy?” Mouton asks. “You can’t put your finger on it,” he says, and he’s not sure Chenier could have either.

As a result, Mouton shares knowledge about Chenier, but he can still talk like a fanboy about the ineffable. “He had a near-psychic ability to rock the house,” Mouton says. “He knew when to play a slow song, when to play a fast song, when to play a waltz. When to play a song that people might have heard but to put it in French, then translate it to English so it was more familiar. And did this with a natural grace.”

Because of the limits he faced, Mouton worked to understand Chenier’s context, and studying him helped Mouton make connections he hadn’t made before. He came to think of him in the same way we think of Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters and Bob Marley—someone who popularized a sound by putting it in terms that let the uninitiated in without compromising the music’s integrity. According to Mouton, “You go anywhere in the world and people know what reggae is. Why? Bob Marley. You go anywhere in the world and people know what zydeco is. Why? Clifton Chenier.” Mouton doesn’t think of either artist as self-consciously exploiting anything, but both synthesized the popular sounds of the world around them into music that could speak to broad audiences despite their strong idiosyncrasies.

That doesn’t mean Chenier was entirely intuitive, though. “He had all these badass Texas guitar players in his band,” Mouton says, and they helped audiences connect to Chenier’s South Louisiana take on the blues.

Working on Way Down in Louisiana helped Mouton make some connections. As much as people like to think that you have to hear Cajun and zydeco music in Louisiana, Chenier demonstrated that that wasn’t true in 1964 when he packed up the band and headed west to California, finding favorable crowds all the way. People assume that the music sounded exotic then, but time helped Mouton appreciate that trip from Chenier’s perspective as well.

“Those experiences had to be exotic and different for Clifton and his band as well,” he says.

Mouton’s research led him to believe that Chenier could be inscrutable, but he was also driven to “rock the house.” The phrase sounds like an empty promise made nightly by the lead singer of a reunited hair metal band, but it takes on meaning when Mouton uses it to describe Chenier’s intensely focused single-mindedness. “He was there to rock the house, then he was on to the next thing. When he was in the recording studio, he wasn’t concerned with documenting something for posterity, or creating great art. He was there to rock the house, then he was on to the next thing. It just so happened that he rocked the house for four hours a night for nights on end. Was he a guy you’d sit down with and hang out for a long time? It doesn’t seem so. Did he have a lot of big philosophies on life? It doesn’t seem that way. He was very driven, but when he wasn’t on the bandstand, he was on to the next place and going over musical ideas in his head.”