Robert Gordon's Memphis Rent Party Comes to New Orleans

The writer of "Memphis Rent Party" presents the keys to the city before coming to Octavia Books Friday for a conversation and signing.

Writer and filmmaker Robert Gordon has made a career of documenting Memphis’ music and the underground culture associated with it. In 1995’s It Came from Memphis, he folds disc jockey Dewey Phillips and professional wrestling into an account of the music scene that swerves noticeably around the city’s two biggest successes—Sun and Stax Records. They’re looming presences that affect the lives of many of the people Gordon writes about, but they’re not the focal points they would be in the hands of other writers.

“I love shining a light where it’s usually kept dark,” Gordon says. “I’m not so interested in the big hits; I’m more with the Sam Phillips way of thinking: Give me something different.”

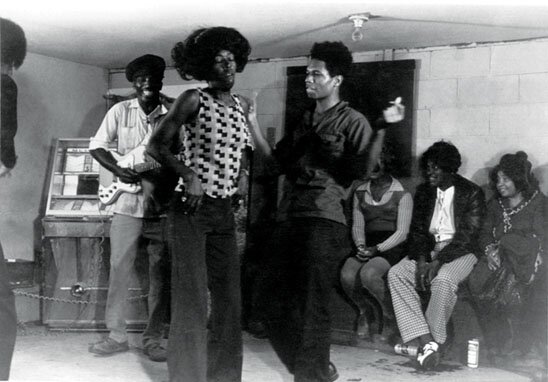

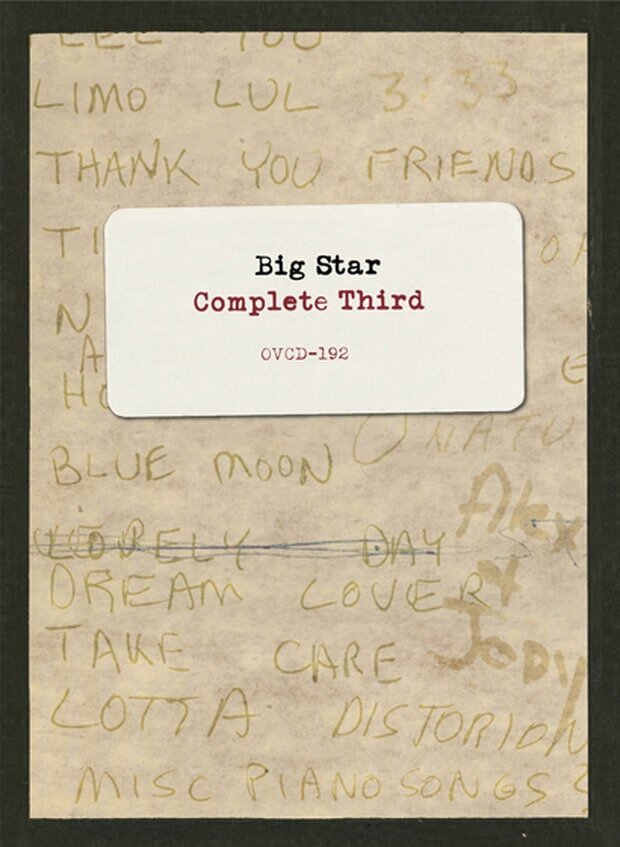

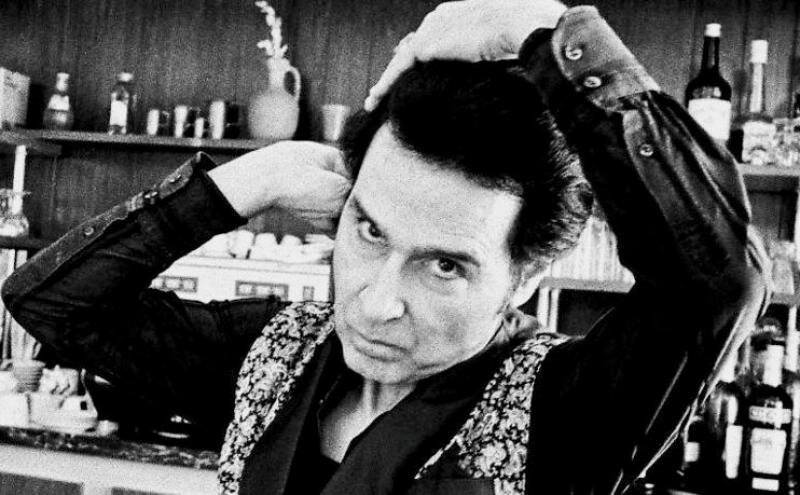

Gordon’s most recent book, Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music's Hometown, tells stories of some of the figures important to the way he thinks about Memphis and music—Sam Phillips, Jim Dickinson, Furry Lewis, Alex Chilton, Cat Power, Otha Turner, and more. His choices are personally meaningful, but the figures are (or were) substantial enough to bear the weight of significance he lays on them. Fat Possum Records released an accompanying soundtrack that makes plain the wild, idiosyncratic sensibility that speaks to Gordon, and like his choice of subjects, the tracks themselves are deep cuts. A live take of “Drop Your Mask” from Panther Burns’ second gig, a cover of The Slicker’ “Johnny Too Bad” by Alex Chilton, and “Harbor Lights” by Jerry Lee Lewis are among the highlights.

Gordon will be in New Orleans for a book signing and conversation with Michael Tisserand Friday night at 6 p.m. at Octavia Books.

Is there a common thread that runs through your histories of Memphis other than Memphis itself?

I only saw the commonality for Memphis Rent Party in retrospect. And that is the striving for individuality. It’s the pursuit of the Sam Phillips ideal—to be different. And that is what I think Memphis has to offer—the possibility of being different. Sam was once asked why he didn’t move to Nashville and he said, Nashville has a follower’s mentality. Indeed! To me, Memphis is the pursuit of sounding like nobody else, and Nashville is the pursuit of sounding like everybody else. Both can result in superstardom, but the paths are very different, and the odds are more difficult in Memphis. But the claim to history, to art, is much higher in Memphis. (Nashville, to be fair, has achieved art sometimes, alongside its stardom and celebrity.)

What’s the thought that you think is crucial to understanding Memphis?

Memphis is, historically, an overgrown cotton town. It has a small town mentality, is racist and conservative. The art here has always happened in spite of the city, not with its encouragement. The city, in fact, has long rejected it. Music only got civic support in Memphis when, at Elvis’s death, the city fathers saw the world’s reaction, saw the money spent to memorialize him. Memphis’s leaders hate the blues, they just love green more than even their racist views.

In more recent times, I’ve appreciated Memphis as livable. Traffic is rarely an issue, rents and home prices remain reasonable. My friends in Austin and Nashville complain about never finding parking at restaurants and having to wait for tables; not an issue here. Though if I keep saying it, I’m gonna ruin it.

How does the long shadow of Memphis’ musical history affect those who’ve tried to make music in it?

The history of Memphis definitely casts a long shadow. It’s both an embracing shadow, and a daunting one. People continue to come to Memphis to live and record because of the freedoms the city gives them, because of the projections of freedom they get from the city’s past. But at the same time, people sometimes get too wrapped up in that past, too imitative. Here’s the main thing, and a good thing: While recording studios around the world have folded, many in Memphis still survive. People come here to record. They come for the inspiration, the liberation. And in these trying times, we need inspiration wherever we can get it.

In It Came from Memphis, you told a version of the city’s musical history that left out Sun and Stax. Why?

As the opening chapter of both It Came from Memphis and Memphis Rent Party make clear, when I attended an outdoor all-day Rolling Stones concert in Memphis on July 4, 1975, what stuck with me wasn’t the Stones, or Charlie Daniels or J. Geils who opened, but rather the blues guitarist Furry Lewis, who was brought in to help pass time while we waited for the Stones. I didn’t realize it then, though I think it sank in then, that I was more interested in the expression of an individual than in the unified voice of what’s popular. When I was writing for magazines a lot, I never had any interest in the cover stories—Michael Jackson, Madonna, Prince. I was much happier having a piece in the wayback of the magazine, near the ads for X-Ray Specs, about some obscure musician who really moved me.

Would popularity kill my fondness of the oddities? Fortunately, I’ve never had to find out. My favorite rock ’n’ roll band, Mud Boy and the Neutrons, always wanted to be first on the bill, to play before the room got crowded. They were a band for over a decade before they ever released an album. When Jim Dickinson, who sort of led the band, was recruited by Bob Dylan for Time Out of Mind, Dylan said to him, Yeah, Mud Boy and the Neutrons, that’s the band everyone’s heard of but no one can find. Jim marked that as success.