Payton, Shorty, Cleary and Lee Thrive in and Out of the Jazz Fest Heat

Monitor photo of Nicholas Payton at Jazz Fest, by Alex Rawls

The last day of Jazz Fest 2022 featured some expected and unexpected shows on a day when the temperature mattered.

Jazz Fest largely dodged the rain this year, with only a couple of delayed openings as a result. It held off during the festival, and what came down didn’t turn the grounds to mud. The heat was a bigger issue, particularly on Sunday, when people were heading for the tents to get a break.Those packed into the WWOZ Jazz Tent for Nicholas Payton got a fascinating show, though one they almost certainly hadn’t planned on.

It took an extra 20 minutes to set the stage for his band, which included Sasha Masakowski on a cafeteria table covered in controllers, pads, gear, and a laptop; and Cliff Hines, who had a patch bay, a laptop, and an electric guitar. Payton had an upright bass, an electric bass, his trumpet, a Fender Rhodes, and another synth on top. As that list might make clear, Payton didn’t envision or play an hour of Miles Davis-inspired jazz.

He closed with “Jazz is a Four-Letter Word” from 2017’s Afro-Caribbean Mixtape, and the track’s title felt like an exclamation mark/statement of purpose for the set. Payton has long argued that jazz is the wrong genre for him, and that #BlackAmericanMusic is more accurate. On Sunday, he offered up a set that certainly worked with jazz components, and on occasion he turned to his trumpet to solo over the pulsing mass of sound that the three were creating, but more often the amorphous mass of sound that owed debts to dub, hip-hop, and techno was the musical expression and really, when he went to his trumpet, what he played was better understood as an additional part for the song than a solo.

It’s hard to be certain, but much of the music started with Payton or his laptop, where he had samples of speakers. “You can’t trust the untrustworthy,” one voice said, then he played parts on his basses and keyboards that were looped and collectively morphed into music that moved constantly but slowly, so much so that if you focused on the bass passage or the Fender Rhodes, the pieces didn’t seem to go anywhere.

Payton played with this lineup on a number of COVID livestreams and released an album with it, Quarantining with Nick. His livestream shows regardless of the lineup were all about vibe, with the drums ticking out electronically. Those shows and Sunday afternoon’s were not displays of instrumental prowess, though Payton played with clear care and feel, particularly on the Fender Rhodes and the upright bass. There was a lot of interaction between the players, but it came in the form of each adding elements to the sound based on someone else’s musical choices, or manipulating those changes to make them into something new. The music represented a conversation, but it wasn’t one took place as solo spoke to solo.

The audience didn’t leave. It was hot as hell outside the tent, and many were staking out space for Norah Jones, and the weird electronic music was the price of seating for that show. They didn’t know how to respond to it, and to be fair, it wasn’t obvious how they should. There was respectable applause after each time Payton played his trumpet, but that felt more like an occasion to break the tension because the pieces simply went on and for more than 10 minutes each. It was interesting though, that the few people under 20 that I could see were the people most obviously engaging with the music. One guy was shooting video on his phone, and people who were likely part of the NOCCA Jazz Ensemble not only interacted with the hip-hop elements, but they heard humor in the music—humor that was there but delivered with such a straight face that it was easy to miss, particularly for audiences used to assuming that jazz is serious business.

On Sunday, my review of Trombone Shorty’s new Lifted contended that on record, Shorty has worked too hard to do things that make him conventional and forgettable. When he closed out the Festival Stage that afternoon, he made clear what is missing on the album in his performance. He’s a very democratic band leader who gives the musicians their time in the spotlight, but the show is all about him and his star power. He went out to one wing and played an extended trombone solo by himself in front of a Shell backdrop to give us the musical and visual spectacle of the moment, and when he wanted someone else to take a solo, he walked over to that musician and brought the audience’s attention with him. He knew he had all eyes on him and used that to build his band and the moment.

He didn’t serve the songs on Sunday; they served him, giving him vehicles for solo moments or moments with Orleans Avenue. He spent much of his first half-hour on his version of Allen Toussaint’s “On Your Way Down” and his own “The Craziest Thing,” and while he took the songs seriously, they felt like connective tissue to string together the show, not the reason Shorty plays.

If you wanted to grouse, you could probably say the songs get to little attention in the show, and I’ve had that complaint in the past with shows by his mentor, Lenny Kravitz. But bluntly, I liked Lenny’s songs better than his band’s efforts at jamming. Shorty and Orleans Avenue’s time together onstage is clearly the reason for the show.

It was also nice on Sunday to see the crowd for Shorty. There have been years where his stage-closing set has felt like the afterparty for whatever visiting star played in front of him—Jimmy Buffett this year—but he played to one of his biggest Jazz Fest crowds since he became a closer. Is his audience trending up? I hope so, but like so much about this year’s Jazz Fest, I need to see at least two years of results to know if we’re seeing growth or a response to the first Jazz Fest in three years.

Khari Allen Lee paid tribute to sax player Grover Washington Jr. in the WWOZ Jazz Tent, and although he get an enthusiastic response to “Mister Magic” and “The Two of Us,” the audience at Congo Square Stage waiting for Kool and the Gang and Frankie Beverly and Maze would have gone nuts for those versions.

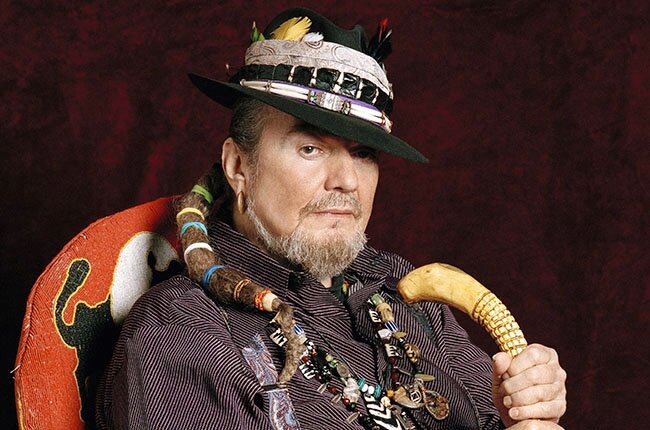

I tend to shy away from Jazz Fest tributes to important artists in its history because either family politics keep them from being what you hope for, or they’re made to recreate the favorite songs in too faithful ways, muting the artistic voice of the artist paying tribute. Jon Cleary threaded the needle beautifully when he performed “Such a Night” at Sunday’s Dr. John tribute. You could quickly hear that Cleary doesn’t phrase lines like Mac, and rather than slip into impression, he stuck with his own phrasing. He’s also not as showy a player as Mac was when he recorded the song in 1973, so Cleary’s rhythm wasn’t quite so high-stepping. But by being true to himself, Cleary’s version felt genuinely affectionate, and the sly little solo he took that served as a false ending was charming and effective. On the whole, you could hear both Cleary and Dr. John when Cleary performed, which helped you appreciate Mac’s version while enjoying Cleary’s.

Creator of My Spilt Milk and its spin-off Christmas music website and podcast, TwelveSongsOfChristmas.com.