Most of What You Think You Know About James McMurtry is Wrong

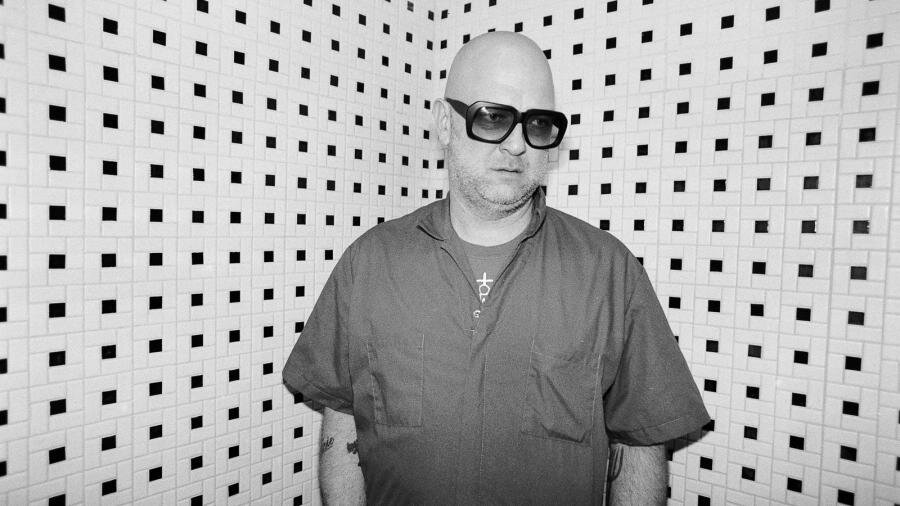

The Austin-based singer/songwriter isn't surly; he's just working.

When I listen to James McMurtry, I feel like I understand libertarians and small government Republicans. Those aren’t the Austin singer/songwriter’s politics; his best known song in recent years is “We Can’t Make It Here,” an across the board takedown of the Conservative efforts to shift more wealth to the wealthy. A close second is “Cheney’s Toy,” an indictment of American militarism under President George W. Bush, but the people in his song live in those spaces where the town meets the country, so they have one foot in a semi-urban working world that rarely serves them well, and one in a rural environment where they can do what they want. In song after song, you get the impression that what the people in McMurtry songs want more than anything else is to be left alone.

That may be in part an extension of McMurtry’s persona. In person, his face settles into a “Why are you talking to me?” look, and his voice has a serious intensity that quickly conveys that whatever you say next better be good. It’s easy to hear his characters as wanting the world off their backs because that’s a quick sketch takeaway of McMurtry himself.

He’ll play One Eyed Jacks tonight with his band, and the band is the first sign that your take’s not quite right. His songs may come from the folk song tradition, but everybody plays electric guitars, so the delivery is closer to Neil Young and Crazy Horse than Dave Van Ronk. He’s a rock ’n’ roll guy, and Lou Reed was an inspiration, as was John Hiatt’s time with The Goners—Sonny Landreth, Dave Ranson and Kenneth Blevins. Young was less formative than McMurtry’s sound my suggest. He had a year or so as a teenager when he was into Neil Young, but Young didn’t really register until he played with Crazy Horse.

McMurtry writes convincingly about people who live much of their lives in rural environments, but for the most part he’s a city guy. His grandfather was a rancher in North Texas so he spent time there, and many of his friends when he grew up in Virginia lived in the country, but “I’ve lived mostly in cities most of my adult life,” he says. McMurtry does like to fish when he can, and he enjoys deer hunting. The camp he goes to is five hours away though, so he doesn’t hunt as often as he’d like.

McMurtry identifies with his characters to the extent that he shares their working class sensibilities if not lives. He’s the son of writer Larry McMurtry, so he comes from a family with a leaning toward the arts, but he like guys on the assembly lines that were shut down in “We Can’t Make it Here,” McMurtry has no romantic notions about self-expression. “In some sense, a song is a tool,” he says. “You’re crafting a tool to use in tonight’s show or tomorrow’s show. It can also be seen as a piece of art. It’s not that I don’t enjoy it, but I enjoy having written a good song more than I enjoy the process.”

He was more caught up in the mythology of writing when he was younger, when he wrote compulsively and filled up books with lines, notes and ideas. But while his dad would celebrate well-turned lines, that was never McMurtry’s style. Writing is his job, and he treats it like one. The roofer doesn’t celebrate the well-nailed shingle. Part of the job is attending to the music of the words, which means McMurtry pays attention to meter and rhyme and sound of the words. That sometimes forces him to make choices that he might not have made otherwise, often for the betterment of the song.

“I’ll scan though my computer files and look for things that happen to fit the same meter, even if they were written years apart, and see if they go together and make sense as a song. Another thing about a song is that it doesn’t have to make perfect sense. It can be a total non-sequitur but sing well and be a cool song.” The latter realization came to McMurtry after he heard John Prine’s “Jesus: The Missing Years.”

“He has the whole rambling thing about Jesus, then the chorus comes along and has nothing to do with the rest of the song,” McMurtry says. “And it’s a lovely chorus. Charley bought some popcorn / Billy bought a car / Someone almost bought the farm but they didn't go that far.”

Unlike workers, McMurtry writes when he has to and rarely before. He tours for much of the time between albums and only goes into the studio when he feels like he’s traveled as far as he can on the songs he’s got. His most recent album, Complicated Game, doesn’t have the overtly political moments of Childish Things and Just Us Kids—his last two albums of new material. Instead, it focuses more on stories and people; any political statements are extensions of their dramas. “Carlisle’s Haul” depicts a commercial fisherman fishing out of season because he needs the money, and while McMurtry sympathizes with his plight, he doesn’t share his politics.

“I believe we ought to regulate fisheries so we’ll still have them,” he says. “But I don’t make my living as a commercial fisherman like that guy does.”

In the past, recording for McMurtry meant going into the studio with his band and banging out takes until they have one “with some life in it.” When C.C. Adcock and Mike Napolitano produced Complicated Game in New Orleans, it was nothing like that. McMurtry met Adcock at The Continental Club, where both play when they’re in Austin, and they developed a relationship there. In the studio, Adcock and Napolitano built the songs track by track. “I’d come in and do a take with vocal and guitar to a click track, then do a clean guitar track with no vocal on it,” McMurtry says. “Then we’d replace the vocal, and then we’d listen and go, Okay, do we want to add drums to this or not?”

That’s not his preferred way of working, but it suited the realities of his career. McMurtry’s money comes on the road, and even if he had the money to hole up in a studio for a month or so to make an album, he and his band can’t take a month without gigs. Instead, he’d come to New Orleans, lay down some tracks for a few days, then fly back to Austin, get in the van with the band and go to work. “Meanwhile, Charles and Nappy would go through the tapes saying, Okay, do we want Ivan [Neville] to sing on that?” Adcock and Napolitano brought in former Heartbreaker Benmont Tench for a week to lay down organ parts for the album, and he got his parts done without ever meeting McMurtry. McMurtry did, however, see one of Neville’s harmony vocal sessions and was blown away. Or as blown away McMurtry can be.

“I’ve never seen a harmony session go that smooth,” he says. “Harmony and vocal sessions can be painful, trying to get a singer to match your phrasing and sing the right notes at the right time can be hard. Ivan walked in there and nailed it.”

The precise language and storytelling in McMurtry’s songs suggest that his lyrics are carefully crafted. The vocabulary of “Carlisle’s Haul” is so specific that it’s easy to imagine him doing research to find it, but that wasn’t the case. What little he knows he picked up as a teenager in the ’70s while visiting a friend’s summer house near the mouth of the Potomac River. For the most part, McMurtry writes syllable by syllable, finding his story a detail and action at a time. Because the characters in his stories are so concrete, it’s tempting to assume that he has thought them through. That, like most assumptions and conclusions you’re inclined to draw about James McMurtry, would be wrong. How well does he know the people in his songs? “About as well as you know someone at the end of the bar who you talked to for three hours for no particular reason.”

How well does he have to know them? “Not well at all. You just have to have enough words to make the song.”