"Krazy" Tells the Black and White Story of a Man at Work

Michael Tisserand tells the story of the comic art legend and "Krazy Kat" creator George Herriman through his newspaper work.

When Dana Carvey talked about growing up with an angry, abusive father on WTF with Marc Maron, his story is disturbing but not that unusual. Since Maron’s interviews comedians, rough family relationships border on the de facto starting place. When Carvey talked about crashing his career after Saturday Night Live, the specifics of his mediocre career and acting choices come to life. They’re individual, and they’re the place where we connect with his story. They’re movies and shows we saw or chose not to see, and really, they’re part of the story we wanted. How did that happen?

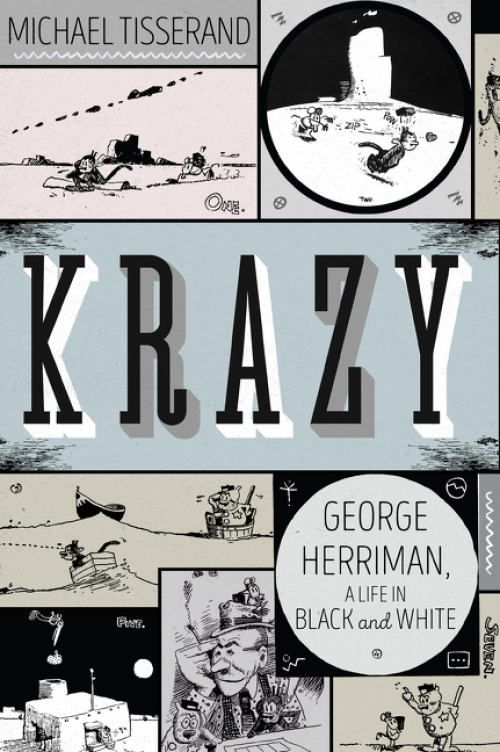

In Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White, Michael Tisserand takes a similar approach to telling the story of the New Orleans-born newspaper comics artist George Herriman, who created the classic "Krazy Kat" strip in the early 1900s. Tisserand will read and sign copies of Krazy tonight at Octavia Books.

After Herriman leaves New Orleans, Tisserand tells his story through his work, following his career as an itinerant cartoonist, bouncing from newspaper to newspaper and coast to coast as he created dozens of short-lived comics en route to "Krazy Kat". He tracks how the elements that Herriman would play with in "Krazy Kat"—language, culture, gender, and race—become part of his artistic arsenal in comics that are otherwise unmemorable, and how Herriman revealed himself, if only momentarily, in his work.

The approach is necessary because Herriman didn’t leave behind a materials that genuinely revealed him. Tisserand starts his book in New Orleans in the Treme, where Herriman’s extended family were free people of color. The passage is the most narratively compelling part of Krazy as it depicts what New Orleans was like in the late 1800s for free people of color, and how they saw their world coming down around them in the 1880s, when violence against blacks was more prevalent and education opportunities for black children were narrowing. That led Herriman’s father to move the family to Los Angeles, where George and his family chose to live “passé blanc”—passing for white. It was a high risk strategy since Herriman’s career could have collapsed around him if he was discovered to be black, and perhaps for that reason, he kept his private life private.

On the other hand, just as "Krazy Kat" played with identity, he created one for himself with the aid of the other cartoonists and sports writers—his main gig in pre-photo does was sports cartooning with a particular interest in boxing. Papers he worked for had stories about “George the Greek” going with other from the paper to the track to play the horses or having a night at the fights turn into a bar crawl. There’s no evidence that the others knew that they were creating an alternative identity for him; more likely, they were simply embellishing the stories for their own amusement as much as the audience's. Tisserand writes with a light hand, and he lets readers draw a lot of conclusions for themselves including what his peers knew. When minstrel and blackface tropes showed up in pre-"Krazy Kat" work, Tisserand leaves it to readers to decide if Herriman was hacking out familiar jokes, employing them as a screen, or being very, very subtly subversive. Tisserand draws attention to the high spots in Herriman’s checkered pre-"Krazy Kat" strips, but he lets readers decide how successful a cartoonist he really was at the time.

Krazy focuses on Herriman as a working cartoonist, and because of that, it also acts as a love letter to a newspaper world that he and his creations inhabited. When one boxer was thought to be ducking a challenger, Herriman drew the challenger in a scene above the fold, then drew a narrow chimney to a smaller panel below the fold where the champion hid. Even before the Internet changed newspaper publishing, it was impossible to imagine page designers composing a page around a gag that elaborate. It’s hard to conceive of a day when newspaper writers were so self-referential, and a day when comics commanded the kind of real estate that they did in Herriman’s day. He composed "Krazy Kat" for the full page and showed as much creativity in his visual storytelling as he did in his gags and the characters’ language. Today, when comics are so small that cartoonists rarely draw backgrounds, the visual richness of "Krazy Kat" is inconceivable.

Tisserand’s evocation of that world is one of Krazy’s strengths. Because that was a guy’s world, Krazy is a guy’s book, one that tells the story of a man who probably never wanted his story told and did his best to make it a challenge. By telling Herriman’s story through his work, Tisserand reminds us of why "Krazy Kat" remains an important piece of 20th century art that remains vital, particularly at a time when the comics page is sad echo of what it once was.