Jean-Jacques Perrey Imagined the Future on "Moog Indigo"

The recently reissued 1970 album by the French electronic music pioneer anticipated an optimistic musical future that now seems charmingly quaint.

[Updated] Today, an electronic music producer can travel with little more than a briefcase for his or her gear. That was not always the case. Just as computers filled rooms and not just desktops in the 1960s, early synthesizers moved with the ease and assurance of arthritic grandparents. Patricia Leroy remembers the Moog synthesizer that belonged to her father Jean-Jacques Perrey as “a keyboard with a lot of stuff on top of it,” she says, laughing. “There were innumerable small cables that led from one hole to another. It looked like an old telephone switchboard. It didn’t look like a music instrument.”

Perrey’s Moog synthesizer “was the second ever instrument that Bob Moog made up,” Leroy says. “One that Bob Moog personally drove to my father’s studio in New York.” Moog assembled the synthesizer in front of Perrey and taught him to use it. Perrey was an early advocate for electronic music, recording The In Sound from Way Out in 1966, Kaleidoscopic Vibrations in 1967 (both with Gershon Kingsley), and Moog Indigo in 1970. Recently, Vanguard Records reissued Moog Indigo for the first time on an audiophile-quality 180-gram vinyl.

According to Leroy, Perrey was always interested in the future. “Since his youth, he had read hundreds of science fiction books and seen I don’t know how many movies,” she says. When he first heard the Ondioline—a precursor to the synthesizer—in 1948, he thought of the instrument as a part of the same future as NASA and space travel, which would become a fascination as well. “He ran to the inventor of the Ondioline to beg him to lend him an Ondioline for a few weeks so he could try it for himself.”

Titles from The In Sound from Way Out signal that interest very clearly. The album opens with “The Unidentified Flying Object,” “The Little Man from Mars,” and “Cosmic Ballad,” and between Perrey’s Moog, his Ondioline, and the tape looping he and Gershon employed, they created space age pop instrumentals. By Moog Indigo, Perrey signaled his fascination with space, computers and the future less obviously, but his light funk is animated in every sense of the word by the synth textures of tomorrow. That is in large part because according to Leroy, Perrey was driven by the sounds and the technology more than the music itself.

“For my father, his interest in the Moog and other instruments was the endless possibility of different sounds,” Leroy says. “He had an extremely sensitive ear, and he was very happy to be able to use very specific sounds to play specific tunes because he thought they were absolutely complementary, the music and the sound. He would explore his Moog for hours until he found the sound that fitted the melody the best.”

Today, Moog Indigo and Perrey’s work sounds like it belongs more to the world of cratediggers looking for the latest cool, funky, retro find, but his textures were as face-melting in their time as anything dubstep producers find today. Today, his sounds carbon date Moog Indigo and his body of work, but they also suggest that today's magma-like bass tones may sound just as quaint 50 years from now. The future you hear in Perrey’s music is a Jetsonian one with bleeps and blorps that anticipate an optimistic future, one where technology makes everything possible. Synth-generated trumpets play a fanfare over a synth-generated harpsichord on “The Rose and the Cross” as different eras and aesthetics collide and collaborate

Perrey played the synth parts himself, and Leroy remembers how magical the overdubbing process seemed to her when she watched her father in the studio. She was 16 when she flew from France to New York City to see him record Moog Indigo. At the time, she listened to Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles, but she appreciated her father’s music and was surprised when other musicians felt a need to tell her how talented he was.

“When I was much younger, I would think, Why are they telling me that?” Leroy remembers. “I already know that.” The pop xylophone player Harry Breuer was particularly complimentary, and collaborated with Perrey on albums that the two released under the name The Happy Moog.

“They got along very well together and had lots of laughs,” Leroy says.

When Perrey recorded, he added all his parts to the basic tracks, which was a painstaking process, made more challenging by the instrument he he used. He could plug the Moog directly into the board to record it, but when he used the Ondioline he had to mic it, which wasn’t easy. Fortunately, “he was extremely precise” in the studio Leroy says. “He had everything in his head. I rarely saw him get frustrated because there was a mistake. He rarely made mistakes when he was recording, but he would make mistakes while he was playing and not recording.”

Updated April 6, 12:52 p.m.

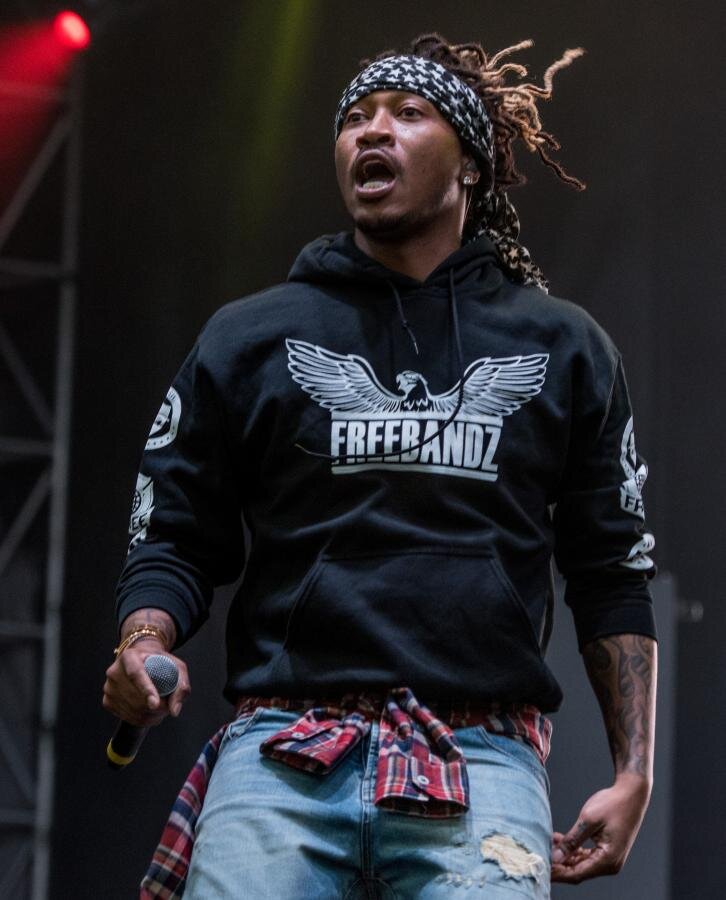

The picture has been changed from one of Robert Moog to one of Perrey. Also, Leroy said that Perrey and Harry Breuer had "lots of laughs," not "lots of love" as first reported.