Jazz Fest: How New Orleans is Jazz Fest, Pt. 2

What do the numbers tell us about the place of New Orleans in the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival?

Yesterday, we asked “How New Orleans is Jazz Fest?” The short answer is “very.” There’s no way to look at lineups that date back as far as 1992 and not see that the booking has consistently been overwhelmingly local, particularly if you add New Orleans and Louisiana artists. Combining them includes Baton Rouge and Lafayette artists, but it also includes musicians that we think of as local even though they’re from the Northshore, Slidell, Harvey, and surrounding regions.

A focus on the bigger picture of New Orleans and Louisiana artists is truer to the question-behind-the-question, which is whether the festival has lessened its focus on regional roots music. It also addresses the reality of who makes “New Orleans music” these days. In the last 30 (probably more) years, so many "local" musicians come from other cities and countries as well as the surrounding region, so insisting on strict New Orleans-ness is akin to the New Orleans high school test, dismissing people if it wasn’t in Orleans or Jefferson parishes.

This spring, I went through 12 years of Jazz Fest schedules to track the festival’s commitment to Louisiana music, and in 2015, 394 of the festival’s 584 acts are from New Orleans (67 percent), with an additional 73 from Louisiana outside New Orleans (12 percent), and 117 from out of state (20 percent). That puts the in-state participation at a robust 80 percent, which is hard to complain about. That includes seven hip-hop and contemporary R&B sets and 12 indie rock and Americana acts—genres that often feel left out of Jazz Fest. Artists in those genres may be underrepresented, but they’re far better represented than they have been.

This year’s NO/LA participation is wind-aided, though. The addition of the NOCCA Pavilion gives Jazz Fest 40 more performance slots and slightly skews the numbers. Take those acts out of the tally and New Orleans artists comprise 64 percent of the offerings on the ground. 2014 skews the other way, when the Brazilian Pavilion added 45 out-of-state artists to the count.

In the last four years, Jazz Fest has presented an average of 574 acts, and on average 363 of those are from New Orleans, 68 are from Louisiana, and 143 are from out of state. Locals have made up 63 percent of the talent, 12 are from the rest of the state, and 25 percent are visiting artists. Overall, 75 percent of the Jazz Fest talent came from somewhere in Louisiana in the last four years.

In the period from 2001-2004 immediately before Festival Productions partnered with AEG Live, the numbers weren’t all that different with, on average, 567 acts—314 from New Orleans (55 percent), 89 from the rest of the state (16 percent), and 161 international acts (28 percent). If anything, the last four years were marginally better for local acts.

Jazz Fest was a smaller festival in 1992-1995. In those years, 404, 410, 430 and 438 acts performed—150 or fewer acts than will grace Jazz Fest stages this year. At most, 92 visiting bands played (in 1995), which breaks down to 13 or fewer inter/national acts a day. By comparison, 2012 was the low for the other eight years with 116 international acts (16 per day), 2002 had 176 (25 per day), and 2014 had 177 (25 per day, though the Brazilian Pavilion added to that number). 2003’s headcounts are all higher than the years around it because the festival experimented with an eight-day schedule. Still, its 185 visiting artists translated to 26 per day.

Still, the percentages don’t suggest that things have changed that much. In the period from 1992-1995, on average 59 percent of the acts were from New Orleans, 20 percent from the rest of the state, and 20 were from out of state. The percentages show a decline in local participation from 2001 to 2004, but those numbers are actually up in the last four years—59 percent from 1992-1995 vs. 55 percent from 2001-2004 vs. 63 percent in the last four years. New Orleans and Louisiana artists made up 79 percent of the performers vs. 71 percent vs. 75 percent. It’s hard to look at the headcount in our samples and see how Jazz Fest has meaningfully changed its commitment to the music of the region.

Another concern that commentators brought up in a Facebook thread on this subject is that the festival doesn’t properly value the local artists, and that they seem like the opening acts for international artists. To get into this question, I calculated the average set length each year to see who played longer than it—who got the most time—and looked at who played before and after 3 p.m., the middle of the day, to see who played for door crashers and early arrivers, and who played in prime time.

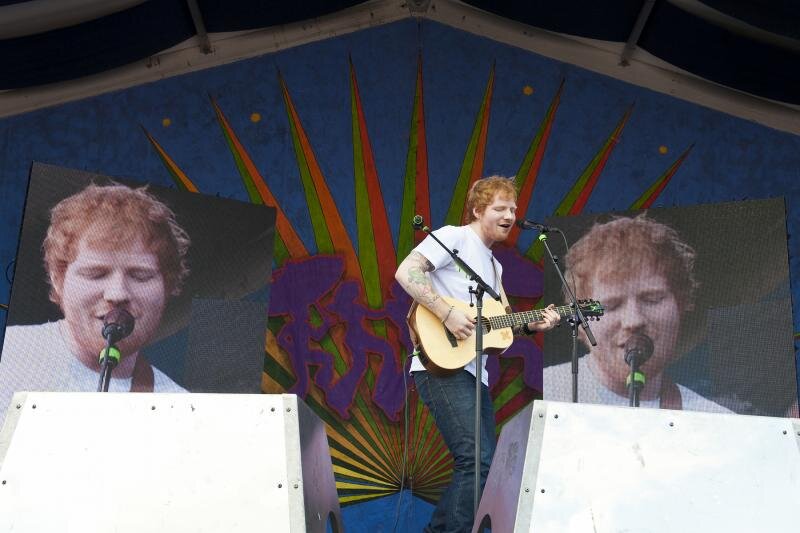

It’s probably not a surprise that these numbers don’t tell as favorable a story. There’s an obvious logic to scheduling. Festival Productions is unlikely to spend national talent money on major artists and give them short and early sets. Similarly, it doesn’t make business sense to book Wilco, Jimmy Cliff or Ed Sheeran and hide them on the tenth line of the festival’s promotional art. They’re booked to help draw audiences. Whether these artists belong at Jazz Fest is a separate question we’ll address tomorrow.

This year, 250 of the New Orleans acts will play between 11:10 a.m. and 3 p.m.—the middle of the day at Jazz Fest—along with 51 Louisiana acts, and 46 national acts. On the surface, that seems disturbing—almost five times as many locals as out-of-town acts—but when the festival lineup is 67 percent native, there will be big numbers on either side of the divide. Still, that constitutes 63 percent of the total number of New Orleans artists, 69 percent of the Louisiana artists, and only 39 percent of the international acts. After 3 p.m., 144 locals will play (36 percent), 22 Louisianans (30 percent), and 71 inter/national acts (60 percent).

That’s a pretty common breakdown for the last four years and the four years from 2001-2004. From 2012-2015, almost 64 percent of local acts, 70 percent of Louisiana acts, and 40 percent of national acts play before 3 p.m. From 2001-2004, 63 percent were local, 60 percent were from Louisiana, and 44 percent were inter/national.

When we go back to 1992-1995, we do see a small difference. On average, locals played before 3 p.m. 59 percent of the time, Louisianans did 58 percent of the time, and out-of-staters did 36 percent of the time. Those aren’t big differences, but the disparities contribute to the sense that something has changed.

Looking at who plays longer and shorter than the average time brings that thought into sharper focus. This year, the average set length is approximately 56 minutes, and that has been more or less the average length for the last four years. Twenty-six percent of New Orleans acts will play longer than that (102), 36 percent of Louisianans (26), and 59 percent of visiting artists (69) will. But by how much? And who gets the most time?

That’s perhaps the most startling thing this study turned up. Trombone Shorty and Orleans Avenue, The Terence Blanchard E-Collective, the Woodenhead reunion, GIVERS and the New Orleans Klezmer All-Stars are among the 13 acts from the state who’ll play 75 minutes, but 26 acts will play longer than any of them, and five will play two hours or more. Wilco didn’t get their full two hours because of rain, but The Who and Jimmy Buffett did. Elton John is supposed to, and on Thursday, Widespread Panic is scheduled to play two and a half hours.

It’s hard to believe, but 26 acts is an improvement. Last year, Irvin Mayfield and the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra played an 80-minute set and Aaron Neville played 90 minutes; otherwise, New Orleans acts capped at 75 minutes while 42 national acts played longer, including String Cheese Incident (two hours), Bruce Springsteen (two hours and 45 minutes) and Phish (three hours). The year before, Galactic and Vernel Bagneris’ anniversary of One Mo’ Time got 80 minutes, Trombone Shorty got 85, but 32 national acts played more than 80 minutes, and Dave Matthews Band, Fleetwood Mac, and Widespread Panic played two hours or more.

This disparity is a part of the post-Festival Productions/AEG Live partnership world. In 2004, only Santana played longer than any local artist, onstage for two hours while Harry Connick Jr. played for 90 minutes, John Mooney played for 85, and The Neville Brothers played for 80. In 2003, Bob Dylan, Widespread Panic, The Radiators and The Neville Brothers all played 90-minute sets—the longest that year—while Tab Benoit and Papa Grows Funk had the next longest sets at 75 minutes each. In the first year we looked at—1992—and New Orleans Music Alumni Association played a two-hour set on the Lagniappe Stage, and The Neville Brothers, The Radiators, CJ Chenier, Dr. John, and Bobby Cure and the Summertime Blues played 80-minute sets (2 hrs in Lagniappe), as did Illinois Jacquet. The only pop artist in the mix that year was Huey Lewis and the News, who had an 80-minute slot as well.

Lumping AEG Live into this conversation isn’t entirely fair because as written, it implies a causal relationship that may be coincidental. As I quoted yesterday, AEG Live encouraged festival executive producer Quint Davis to spend more on talent after the festival lost money in 2004, and AEG Live’s contribution to the festival’s bankroll makes many of those artists possible.

But the separation into Haves and Have-Nots could also have something to do with the lack of credible local closers in the last few years. Trombone Shorty and Orleans Avenue is the only local band to close one of the big three stages three years in a row. While he has been on Acura, Maze has been on Congo Square and Gentilly has featured specialty shows—Preservation Hall Jazz Band’s 50th anniversary show, The Radiators reunion, and this year Dr. John’s all-star Louis Armstrong tribute.

Outside of Shorty, who else can consistently draw and hold big stage audiences? Dr. John is closing a stage this year, but you have to go back to 1997 for the last time he closed one of the big stages—the precursor to the Acura Stage, the WWL/Ray-Ban Stage. If the city isn’t generating that sort of talent, what else can Jazz Fest do with those slots?

Another significant, related difference that has emerged is the way the festival has come to resemble a standard festival, with set lengths growing as the day goes on. In 1992, the average set length was 55 minutes, but 274 sets were within 10 minutes of that average—68 percent of the acts. Essentially, most people got the same time regardless of their stature and draw, but this year, only 44 percent of the acts—258—are within 10 minutes of the average, with 172 acts playing shorter than that and 57 playing longer, many much longer.

The changing distribution in terms of set lengths makes the festival seem less egalitarian and at odds with the utopian hopes many pin on it—fairly or not. And as the stars command bigger and bigger chunks of time and attention, Jazz Fest looks more and more like the commercial marketplace. I suspect many people have valued the festival for so long because it seemed like a respite from it.