Hurray for the Riff Raff is Rethinking Roots Music at Jazz Fest

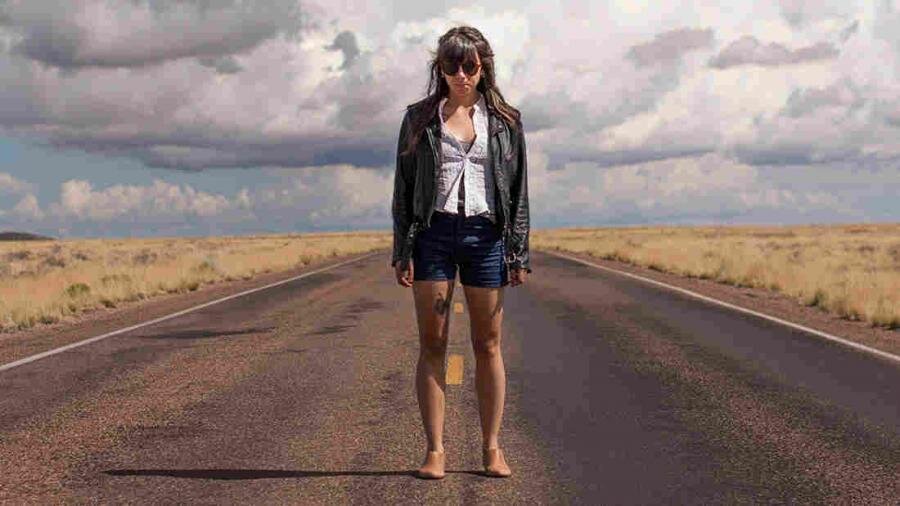

Alynda Segarra is trying to find ways to more accurately talk about her music as she starts work on a new album.

Alynda Segarra’s Hurray for the Riff Raff experience has been one of constant change. The movement from folk, country and blues on 2014’s Small Town Heroes to a more New York-specific blend on 2017’s The Navigator seemed like a big one, but she’d made musical changes before. The first incarnation of Hurray reflected bandmate Walt McClements’ affection for Kurt Weill and experimental sounds, and on 2012’s Look Out Mama and 2013’s My Dearest Darkest Neighbor, you can hear her test-driving Americana with less obvious purpose than she showed on Small Town Heroes.

On that album, her gifts became clear not only as a singer and songwriter but as a conceptualist. She used traditional forms to tell tales from the lives that she and friends led in the Bywater, just as Appalachian songwriters had done a century or more ago. Contemporary lives were ennobled by Segarra’s compassion and the classic forms themselves.

Small Town Heroes made clear that the albums before it were just warm-up laps, and The Navigator does the same. Segarra left behind the Americana trappings but not roots that mattered. “The Navigator represents a departure,” Matthew Ismail Ruiz wrote in Pitchfork. “She hasn’t abandoned those sounds, rather she’s graduated to something singular. It's roots music for the immigrant ID, a folk concept album from a Nuyorican runaway who grew up obsessed with West Side Story before being liberated by Bikini Kill.”

Her Puerto Rican heritage and Bronx upbringing factor far more prominently on the album, and she felt that identity more acutely after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico. In 2018, she set part of the video for her song “Pa’lante” in Puerto Rico as a family tries to put itself back together while the country tried to do the same.

When Hurray for the Riff Raff plays the Acura Stage Saturday at 3:45 p.m. at Jazz Fest, Segarra will be between projects, and while that might not mean much to many acts that play Jazz Fest, it means we can’t be sure what the show will sound like. As a recent conversation between Segarra and me shows, roots are a musical concept from which she’s feeling estranged. Still, last year she sang “Don’t Tell Me That It’s Over” as a one-off single with King James and the Special Men. It’s a classic New Orleans heartbreak song that is faithful in spirit and structure to the heyday of New Orleans R&B, but it’s transformed by the context it lives in. A straightforward heartbreak song sung by a woman who identifies with the LGBTQ community gives the song a fresh vibrancy, even if it sounds like it could be a long lost B-side that someone uncovered. It’s a 45 in a streaming era when the music industry is trying to figure out how to save the album.

We started our conversation there.

What’s the story behind recording “Don’t Tell Me That It’s Over” with King James and the Special Men?

Jimmy [Horn] is a really amazing artist I really love. He’s also a great friend, and he came to me with that song years ago. I was going through a really bad break up, so it definitely spoke to me.

It’s rare that I sing someone else’s song, but there are those moments where you hear a song and you feel this pain or, Wow, I wish I wrote this. I feel this so much. I wish I wrote it. That was one of those moments for me. It’s just such a classic song. It’s one of those very tight, perfect storytelling songs, and when I recorded it with him, I was obviously thinking about Irma Thomas. To me, Irma Thomas, and the recordings that she has made are the epitome of the perfect break up song or, just like heartbreak on tape. And I really wanted to live my Irma Thomas fantasy and go there.

I see on your Coachella setlist a song titled “Kids Who’ll Die.” Is that new? What’s the story behind it?

That is a new song that I wrote based of a Langston Hughes poem called “Kids Who Die.” I was reading it and I thought it was extremely timely, and I felt like it was really great poem to kinda collaborate with. Something that I’ve done in the past is these, like, collaborations with artists that are no longer around that have left us art that is still timely and still speaks to me. It’s been really a cathartic thing to perform, and I’m really excited to record it for the next album.

Where are you in the process of creating new music?

I have a lot of demos done. We’re just going through everything and I’m going to start looking for producers. I’ve been meeting with some people and really want try to start creating the world that I wanna make, because that’s normally what I do with albums—I have a story or I have a world that I want to create, and all the songs become the playlist to the world or the soundtrack of the world. Once I’m done with Jazz Fest, I have a lot to time to focus on making the album and I’m really excited about that.

The Navigator explored a different set of roots from those on Small Town Heroes and Look Out Mama. What is the story in that movement?

I hate to give him any more publicity, but the person who’s occupying the White House right now is definitely a key player in me deciding that I needed to really change direction. I was living in Nashville at the time that I started writing The Navigator and recording it, and Puerto Rico had not experienced [Hurricane] Maria yet, but there was so much in Puerto Rico—debt crisis—and my last remaining grandparent had passed on. I really felt like all these forces were coming together, and I had to make a decision about how I chose to present myself, what I chose to represent, and I really needed to make a choice about being active in my daily life and not just being as passive, like taking a passive role and how people represent me.

I think in the past, even though I’m proud of my past records, I was a little bit more passive about the way that I was being presented to the public. I think I was a little bit more passive about what genre people said I played because genres are hard. It felt like I have so many different interests that I could get lost in the mix, and people could decide what I was as a person in a way that made them feel most comfortable. I felt like with The Navigator, I had to be very clear about where I come from, who my people are, who I stood up for,. Being in a place like Nashville where I felt very out of place and seeing forty-five rise to power were major elements that made me say I have to really take a stand, and say that I stand with Latino people, these are my people, this is where I come from.

I really, on a more positive side, wanted to make my grandparents proud. I was getting a lot of messages from my ancestors and feeling like I wanted them to speak through me. It was a very spiritual time and a very lonely time where I spent a lot of my waking moments writing or really trying to connect with this idea. What do my ancestors want me to say? It was a really intense time, I’m so glad that I went through it, and I’m really proud of what I did, even though it was difficult for some of my audience, but it brought in a lot more people that I am really happy to have at our shows. I also get to feel like I’m myself, and I’m being very purposeful. I feel a lot more charged.

Before Hurray, what was your relationship to roots music?

Before I had this project, roots music was my lifeline. It was what I did to find community. It was what brought me to community, what brought me to safety because when I met the people that I had at hobo camp with when I was 17, the Dead Man Street Orchestra, it was when I finally found for real safety in this traveling homeless kid life that I was living. I met these kids and I felt like, Wow, I have a pack. I have a crew of other musicians and we’re a family, and they’re going to look out for me. It was such a step away from the world that I had been surrounded by, like a lot of drugs, a lot of really negative, scary stuff that I had been surrounded by in the punk scene in New York.

I was able to focus all of my energy on playing music and learning songs and singing and traveling, and it felt like this breath of life when I had been surrounded by so much death before. To me, that music was always like punk. It was the people’s music. It was the poor people’s music. Working people’s music. People of color’s music. To me, race music has always been political. It’s been about telling our stories. It’s been about changing a narrative and letting working people, women, and poor people speak for themselves instead of commercial music speaking for us. That’s what always drew me to roots music.

What does roots music give you as a writer and artist?

I think it’s taught me a lot about storytelling, and it’s extremely unpretentious. In America, everybody used to play an instrument, everybody wrote a song, it doesn’t matter if they were coal miner, it doesn’t matter if they worked on the railroad, it doesn’t matter if they were an enslaved person, everybody had a song. Everybody had the ability to make incredible art. Whether we believe it or not is another thing, whether we’ve been tricked into thinking, Oh, I work at Walmart. I’m not a musician. A person who works at Walmart probably writes way better songs than people who are professional musicians.

So that’s what I learned from it. It’s a history of America, of American people from all over the world and all different walks of life. It’s showing their brilliance and showing you that brilliant people are all over the country. It really gave me this sense of pride about the working people and the struggle of the people of this country, and it made me want to fight for that history. I feel so lucky that I went through this education because there are a lot of people who want to whitewash this history, and they want to claim that white men are the people who started the blues—maybe not started it, but excelled at it and mastered it. That happens so much with race music, so I’m glad that I’m here to be like, You don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about.

So that’s really what I get from it. Education. A sense of pride, and I feel a responsibility to be there in those spaces and be like, Actually, a black woman created rock ‘n’ roll and she was queer. Okay, bye.

Should we think of the phrase “roots music” more broadly than we likely do? I hear “Living in the City” as part of a New York folk rock tradition with Lou Reed, Garland Jeffreys, Elliot Murphy and Willie Nile, but I suspect others would consider that too narrow or specific a tradition to count. I hear a number of subset-like traditions on The Navigator, and I wonder how they affect your ideas about roots and tradition? Do we wrongly assume that “roots” translates to “really old music”?

Well, I think I’m at a place in my life where I want my music to be separate from that genre, and it does make me sad because I feel like it educated me so much and it’s where I began. Like, it literally is my roots. But I’m at a place now where I want my music to get out of that context because people’s ideas are super limited. I also feel like young people today—we’re not really focused on genre’s anymore. We’re thinking about, Is the song good? Does it have a great beat? What is the melody? I think of somebody like Rosalia, who’s becoming a huge pop star. There’s so many people at her concert that don’t even understand what she’s saying. I don’t understand half of it, but it doesn’t matter to me because the music is still incredible. The beats are amazing. It’s like a trap beat with gypsy and flamenco. It’s this very unique perspective that’s all her own. And because it’s so unique, it’s also very relatable. A lot of people feel like, Wow, I’m that age that she did this in. I’m have that unique perspective. Kids look at music that’s very unique and mixing a genre and they think, Oh, I’m a second generation kid from this country. My family came to this country, But I’m influenced by trap. But my family came from here and I have that influence.

That what I think the future of music is, and that’s where I’m going with it. So, I don’t really associate myself with the term “roots” or “Americana” anymore because I just want to make music. I want to have a ton of different influences, and I want to make something that’s good. That’s where I’m focusing more of my artistic perspective. How do I make a killer beat, and how do I make this a unique perspective that is my own?