Flipper Still Lives By its Own Rules

The San Francicso-based band celebrates its 40th year by touring the way it always has and remaining as thorny as ever.

Punk rock specialized in confrontation, but Flipper took it to a new level. By the early ’80s, giving the middle finger to mainstream culture had become ritualized. Be faster, be snarky, and be political. Hardcore was in its infancy, and it added “be wordy and incomprehensible” to the playbook. San Francisco’s Flipper challenged the monoculture that punks found stifling, but it fought punk orthodoxy as well. The band deliberately chose a friendly band instead of something transgressive, and when other bands sped up, Flipper slowed down. Its first release, “Earthworm,” began with bassist Will Shatter singing, “I’m an earthworm / I live in the ground” without a hint of humor or metaphorical intent. It was about the existential angst of being an earthworm.

Flipper will play Santos Bar on Sunday night, and guitarist Ted Falconi was crucial to the band’s omnidirectional F.U. His squalling sound was beautifully ugly, letting feedback and sustained notes bleed into each other to create a discordant cacophony of magnetic sound, difficult but irresistible. He now says by phone that he was out of tune on the early singles and the band’s defining statement, Generic Flipper from 1982, but not as out of tune as you might think while listening to the album. He was just slightly out, he says, because he tuned his open strings to open strings on Shatter’s bass. Shatter then played open notes in the songs, and Falconi found that when he chorded, he was sharp by comparison. “It’s the nature of the instrument,” he finally decided. “The harder you press the strings down over the fret, the sharper you’re going to be. You’re stretching the string when you play a note. It took me years to figure that out.”

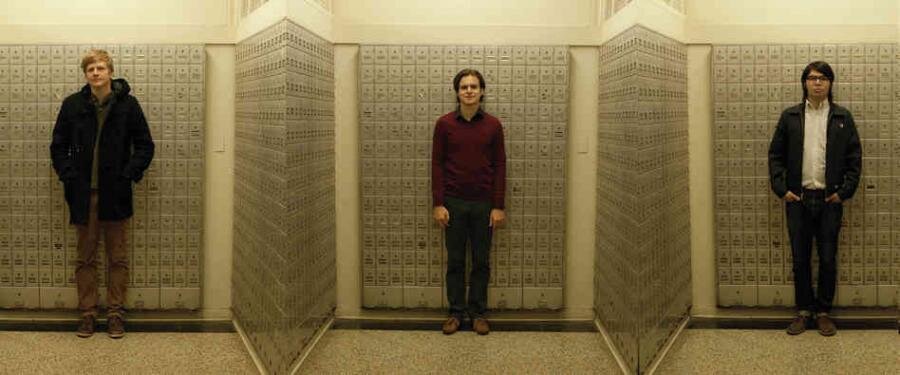

Falconi and drummer Steve DePace are the only two original members of Flipper on the current tour, which features The Jesus Lizard’s David Yow on vocals and Rachel Thoele on bass. When he walks through the band’s history, Falconi and DePace sound like survivors. They had to part ways before the first recordings with founding singer Ricky Williams due to a drug problem that eventually killed him in 1992, and they lost Shatter to a drug overdose in 1987. He had been clean for years, Falconi says, but when he relapsed, he made the junkie mistake of using the amount he was accustomed to at the height of his addiction, not what his cleaned-up body could handle. Bassist Bruce Lose was in a car accident that messed up his back, so much so that it became a problem. “He had some rods and screws put in his back, and it got to a place where he just couldn’t tour.”

Falconi recalls the fates of his bandmates dispassionately, moving methodically through what happened to who in much the same way that he explains his stage set-up and the tour dates before and after New Orleans. There’s no romance in the way Falconi talks about rock ’n’ roll, punk, or playing guitar. He sorts through thoughts systematically, starting at the beginning and moving sequentially through. He didn’t play guitar growing up, nor was he a rock guy. He grew up with jazz. He had his ears opened to Jimi Hendrix while in Vietnam, but when he got home in 1969, he became interested in synthesizers and had an acoustic guitar. After moving to San Francisco, someone stole his guitar. When he was offered the chance to play the electric guitar of John Gulack from local punk band The Mutants, “It was an experience,” Falconi says. “It was louder than I’d ever had that much sound available to touch.” A week later, he had his own electric guitar and amp and started forming a band.

“There’s nothing like the touch response you get to a guitar neck that’s been electrified.”

He didn’t pick up the guitar to get girls or play his favorite songs. He didn’t really care about the guitar at all. It was the electric guitar that moved him, and it interested him as a tool to make his own music. The only cover Flipper played early on was a version of Rick James’ “Superfreak,” and that eventually morphed into the band’s magnum opus, “Sex Bomb.” Even today, he’s less interested in listening to other people’s music and prefers making his own, but when driving, he listens to heavy metal—Sepultura, Lamb of God, and Anthrax came to mind when we talked.

Still, where punk bands subscribed to the Gospel of St. Ramones and kept song lengths religiously tight, Flipper could stretch out—a habit that earned superficial comparisons to The Grateful Dead. The band did jam because, he says, “once you’ve been through a chorus eight or nine times, you start to wonder what else you can do with it.” He thinks his background listening to jazz made it easier for him to be spontaneous, and it gave him a system. “You keep a tune in your head and play off of your head,” he explains.

Jamming was at the core of how Flipper wrote. They found a hook and played it for 10 to 15 minutes, adding parts and subtracting parts, testing parts to see if they made sense, and messing around until the songs found their form.

They knew from their previous punk bands the things that they didn’t want to do, and the completeness of Flipper’s refusal to conform made the band a favorite among critics and other musicians. Rick Rubin and Henry Rollins’ released Generic Flipper and the Flipper collection Sex Bomb, Baby on their short-lived Infinite Zero label, and Kurt Cobain wore a homemade Flipper T-shirt when Nirvana debuted on Saturday Night Live in 1992. R.E.M. and The Melvins covered Flipper, and when Flipper needed a bassist, Nirvana’s Krist Novacelic stepped in for a couple of years--from 2006 to 2008, during which time they recorded one album, Love. Later, Mike Watt played with Flipper on a European tour.

The aesthetic bravery of Flipper’s choices made the band one with a very specific appeal, so much so that its audiences still fit in bars and clubs, just like they did in the early years. The biggest crowd they ever played to was an airplane hanger in Munich that was used to house blimps, but Flipper did that with headliners Fishbone, and the crowd still peaked between 3,000 and 4,000 people. Flipper still tours the way it used to in a van. Falconi remembers with no fondness at all the merciless bench seats in a Mercedes van they recently toured Europe in, and they’ll drive from Austin to New Orleans to play Santos.

Some of the issues the band used to face, it still faces. Flipper is booked through the end of November, but at the moment, they’re not sure Yow can make all the gigs. “Dave works full time,” Falconi says. “He can only take off so many days, and they’ve been letting him play, being a little loose with these four-day weekends. That’s going to be an issue coming up because he’s extended himself past the end of his off-days.

Touring the way that they do makes it possible for Flipper to continue, but each night is a fresh adventure for Falconi. He has a very specific set-up that he uses to get his sound. He feeds the signal into two amps, one dirty and one clean. The way he picks and lets strings ring, he gets what he calls a “full, orchestrated kind of sound.” He has a sound in mind that he tries to get as close to as he can, but the nature of the amps matters. Sometimes he can get that sound from the amps, but he has effects pedals that he can rely on when the amps don’t do what he wants.

“Each different amplifier has its own characteristics,” he says. “A Marshall cabinet is its own compressor, and no matter what head you put on a Marshall, it’s going to sound like a Marshall. Fenders are open backed, full throw, so you get a different sound.”

On this tour, the clubs supply the backline including his amps, so while Falconi can request the kind of amps he wants, he’s at the mercy of what he gets. It’s an interesting challenge, he says, and it’s one he deals with by focusing on the things that matter. “You try to get the sustain right so that I can get long notes,” Falconi says. “I’ll play open strings and partial chords, and I’m looking for that bottom end sustain while I’m picking in the top stuff. It’s like having a right and left hand on a piano instead of only playing with one hand.”

Falconi worked deliberately to create a style that sounded random, and the sonic crud he could generate added an unhealthy element to everything Flipper touched. A cover of “The Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly” could easily have become a bad college rock joke, but the band’s intensity and his guitar sound meant the song was only funny on a conceptual level. “Ha Ha Ha Hee Hee Hee” similarly takes the syllables associated with laughing and exhausts them, even as the song is undeniable.

“Brainwash” is the B-side of the “Sex Bomb” single, and it achieved a new level of perversity, even by Flipper’s standards. Falconi hand-nicked the final groove on the 45s so that the needle would fall back into the previous one and loop until someone lifted the needle. The popularity of “Sex Bomb” meant that the single showed up on the jukebox of punk clubs, where “Brainwash’ would continue until someone kicked the jukebox to get the song to move on. The message in the endless final groove?

“Never mind. Forget it. You wouldn’t understand anyway.”