Dr. John and the Importance of Making Groceries

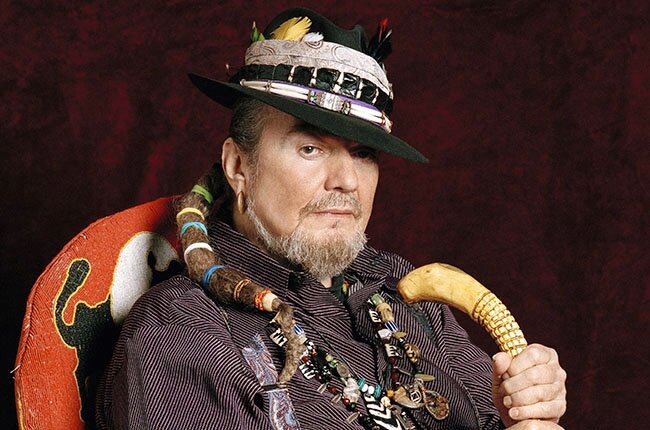

Mac Rebennack left behind a sprawling body of work that for the most part does one task: translate New Orleans to the rest of the world.

Dr. John’s most enduring mode was translator of New Orleans. He covered a few careers’ worth of musical ground and was never simply anything, but after 1972’s Gumbo, that was his gig—to help the rest of the country understand his hometown. Its history, its reality, and its romance. That role resonated in a way that psychedelic explorer of the alternative spiritual planes didn’t, and it was a role that left him room to grow. The Dr. John Plays Mac Rebennack albums allowed him to examine his piano professor inheritance, and over the years he approached the music of some of New Orleans’ most important artists—which means some of America’s most important artists—and found ways to make his versions vital. He added a little of his own carny hustler and the wary eye of a guy who’s seen danger and knows that there’s more around than you know. His Sippiana Hericane and City That Care Forgot presented the resilient, overwhelmed, semi-coherent pain and anger of New Orleanians dealing with the devastation caused by the flooding that followed Hurricane Katrina.

I don’t have Mac Rebennack stories to tell. When I’ve been in positions that I’ve needed Dr. John articles, I’ve had other writers who had more history with him, and I never called my own number just to meet him. Perhaps for that reason, I’ve loved all pieces of Dr. John lore. I loved when a member of one his bands said that they had to know 100 songs when they went on tour, and he’d get to most of them sooner or later. That seemed like so much more than he had to do as a man in his 60s at the time. Another companion said he traveled heavy, carrying whatever he needed to make a hotel room into a space that made him feel comfortable. One person used to picking up musicians at the airport with their guitars and knapsacks discovered that she didn’t bring enough car to pick up Mac and his stuff. One musician’s wife remembered how, out of nowhere, Mac called her husband one night just to shoot the shit for more than an hour. The late Bobby Charles recalled the same thing—that Mac would call him at times just to talk and bullshit. I love the idea that Dr. John was a phone guy.

Dr. John was such a strong musical idea that all of these mundane things seemed unlikely, but all of the stories of random encounters with him in the streets and in stores—many of which people are telling on Facebook right now—seemed natural at the same time because of course Mac Rebennack has to eat. He was easy to root for because he was a hometown rock star who was genuinely accessible. Like so many New Orleanians, I was happy for him when he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2011. I have mixed feelings about the institution, but I was glad to see him get the honor while he could enjoy it. I was similarly pleased when a year later the Dan Auerbach-produced Locked Down came out and earned him the best reviews he’d received in a long time. (Here’s mine.) Critics and fans loved the return of the Night Tripper, and he made sense in the company of Auerbach, Buddy Miller, and Don Was when he performed in Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium after receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Americana Music Awards in 2013.

Locked Down understandably renewed interest in The Night Tripper and his earlier work, but it had never entirely gone away. In 2006, he performed at Bonnaroo as the Night Tripper, and in 2013 he did a Night Tripper show at the Voodoo Music and Arts Festival with an all-star lineup of New Orleans talent that included George Porter Jr., David Torkanowsky, Ivan Neville, and Nicholas Payton. Those shows were strong, but they, like Locked Down, took Dr. John to a musical place where he didn’t live anymore, and it was no surprise that he eventually returned to the subject that carried him through the previous four decades—New Orleans.

I didn’t connect to his last album, the Louis Armstrong tribute Ske-Dat-De-Dat: The Spirit of Satch, but Rebennack was excited by the idea when he announced that he was recording it. And the choice made sense. Armstrong was New Orleans’ ambassador to the world before Dr. John took up the mantle, so his songs left less room for Mac to assert himself. Still, the album helped him headline at Jazz Fest one more time in 2015—something he hadn’t done in more than a decade—and brought him back to the Fair Grounds, a place he hadn’t been since his new band was poorly received in 2013. When he wasn’t on this year’s Jazz Fest lineup, more than one person I ran into on the grounds wondered about his health.

Since Dr. John died, I’ve been thinking about an exchange I had with Texas songwriter Jon Dee Graham when Alex Chilton died. “Giants falling right and left,” he wrote in an email. “Who can even pretend to the size of these immortal dead? Who WANTS to?” That last thought is one I’ve been circling back to. Who’s dreaming as big as Rebennack dreamed, and who’s aspiring to leave behind such a broad and varied body of work? One that could speak to the once-a-year Jazz Fester who only really knew “Right Place, Wrong Time” and still engage fans who had seen him dozens of times? Who wants to be big enough to speak for a city, a state, or a country? And who’s willing to go out on some crazy thin limbs to do it? I’m glad to see young musicians make sensible decisions because it’s harder to make an impact if you’re not in the game, but I also wish I saw more musicians take more big chances and gamble on an idea as unlikely as a stage show built around a legendary voodoo priest. And, if they’ve taken that chance, then go make their own groceries.

For more on Dr. John, see Alison Fensterstock's excellent obituary for NPR and pianist Tom McDermott's list of the best of Dr. John for The Daily Beast.