Colbert, WWE, and Musicians Deal with a World without Crowds

What changes when there's no audience in the room?

On Tuesday night, Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders spoke after the results of the Arizona, Illinois, and Florida primaries had been called for Biden. Instead of the usual shouted triumphalism of the winner and the C’mon everybody! We’ll get ‘em next time! of the loser, both dialed down the volume. Biden spoke from his home in Wilmington, Delaware in a suit and in front of a pair of American flags he just happened have handy, and he spoke calmly but resolutely to people in their living rooms, clearly trying to tune himself to the gravity of the moment. Sanders spent his time not rallying the troops and instead proposed measures to slow the damage done by the Coronavirus pandemic, and he did so in similarly hushed tones.

For me, these addresses were fascinating because they’re atypical, and since television’s calling card is familiarity and repetition, it’s rarely atypical. Sadly, such moments usually come with disasters—occasions when events overtake the production and reporting mechanisms of news outlets. I remember very clearly the feeling that America might be at war in the first three or four hours after 9/11 and the bombing of the World Trade Center. Newsrooms emptied, trying to find anything related to what happened and passing it almost unedited to on-air staff that had to try and piece together fragments of information before a clear narrative had emerged. Every factoid seemed more ominous and more like we were on the verge of World War III. We were, but it felt like a more conventional war than the one we ended up in was eminent.

The current break in TV protocol comes from a disaster as well, but not from being surprised by a story that emerged out of nowhere. In this case, it’s a product of social distancing and the potential to spread the Coronavirus that accompanies large crowds. Biden and Sanders would likely have loved to have a hotel ballroom full of cheering supporters, but not at the expense of seeming responsible and presidential.

The late night talk shows made similar choices or, more likely, had the decision to work without an audience made for them by the networks, which would go on to shut down production of the shows like they shut down productions of their prime time programming because TV needs a lot of human capital. Last Thursday, The Late Show with Stephen Colbert did an episode from the show’s home in the Ed Sullivan Theater with Jon Batiste, the band, and an audience made up solely of show staffers, and clearly they learned during the day that they wouldn’t have the usual live audience. Stephen Colbert performed his monologue from his desk with a cocktail in hand as a prop, and it sort of worked. One thing became clear though—the set-up/punch line rhythm of a joke doesn’t work without an audience. The audience’s responses helped shape the timing of the set-up and the impact of the joke, so without a crowd, the monologue didn’t work very well. On Wednesday night, Colbert said that when he does his monologue, he does it for the audience and “with the audience,” something the Thursday night show made clear.

Still, I figured that if anyone had the intelligence and nerve to figure out how to do that specific, post-Jon Stewart brand of late night political comedy without an audience, it would be Colbert. I craved that comedic voice and was disappointed to see that Late Night with Seth Meyers went to reruns after its show last Thursday night. A version of it has been on the air in one form or another since Stewart took over The Daily Show in 1999, and it’s a normalizing element in very abnormal times.

Fortunately, Colbert proved me right. On Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday this week, he performed new monologues that he shot via FaceTime from his home, and those monologues were followed by reruns of interviews.

He performed one from a tub full of bubble bath, one from a backyard next to a fire pit, and one from his porch, which is very Colbert. One of his talents is the ability to create the right context for his jokes, but the jokes themselves morphed slightly because there’s no point in one designed to slay a roomful of people that aren’t there. His jokes this week more moderate in their aspirations, wryer, and even though writers surely contributed them, they feel even more true to Colbert when taken as a whole.

Moments like these reveal a lot of machinery behind television that we barely notice. On last Thursday’s Late Night with Seth Meyers, Meyers saw no point in a suit if there wasn’t an audience there and performed instead in a blue, button-up shirt. Trevor Noah has continued to do The Daily Show video content that he’s clearly shooting on his phone, often unshaven and wearing a hoodie. The Daily Show plans to continue a digital version from staffers houses for the foreseeable future, and you can see him work on a rhythm and concept that makes sense when effectively speaking one to one with someone on FaceTime or Skype, letting jokes emerge when they will in a lumpy form.

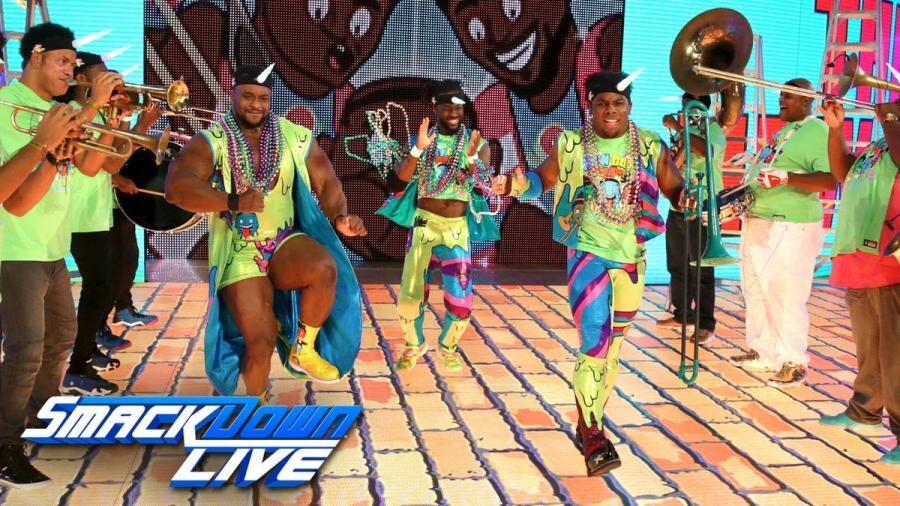

The oddest Coronavirus-inspired change to television is professional wrestling without an audience. The WWE was scheduled to broadcast Friday Night Smackdown live on Fox from the Smoothie King Center this week, but the company has moved WWE Raw and Friday Night Smackdown to its training facility, the WWE Performance Center in Orlando, Florida. Professional wrestling without a live audience seems particularly challenging because the best wrestler isn’t the one with the best moves or the one who wins the most; it’s the one who gets the biggest reaction. What happens when there’s no crowd to play to?

It turns out, a lot. Or a lot can happen. So far, the strengths have been promo segments that often seem corny as “WWE Superstars” air their sides of feuds in loud, broad terms designed to make sure that the people in the back row get them. On the socially distanced Raw and Smackdown, the promos were quieter, more intense and more effective as a result. On occasions when the performances pushed their performances over the top, that had power too as it made the moment seem claustrophobic with too much emotional energy coming too quickly into your living room.

Still, the WWE has some kinks to work out. This week’s Raw concluded with the legendary “Stone Cold” Steve Austin making a special appearance to deliver a segment that would have killed in front of an audience weeks before. In the Performance Center, it fell flat. Not exactly flat, but you had to already be invested in Austin to be amused. His gift was working the crowd, and he came to the ring to his usual music, slinging and drinking beer in ways that just seemed silly without people there to celebrate his maverick spirit. He climbed the ropes in each corner of the ring to get closer to crowd, just as he always has, but there was no one to get closer to. It felt like a ritual, but one without meaning in this context. Austin then delivered obviously scripted jokes that weren’t funny but got stagey, hokey laughs that would have embarrassed junior high dramatic arts students from announcer Byron Saxton. The segment suffered from an ongoing WWE problem—people talking in ways that people don’t talk—but the effort to play to a packed house that wasn’t there only made clear that the broadness of professional wrestling doesn’t make any sense out of context.

On Wednesday night, the upstart wrestling promotion AEW also worked in an empty arena on Dynamite, and it aired a show that says the concept can definitely work. The matches’ structures helped to give them some drama, and AEW put wrestlers that weren’t working at ringside to add some noise and energy, which took some of the sterility out of the atmosphere.

The next week or so is a test for the WWE to see what it can learn before the biggest event in its year, Wrestlemania, takes place April 4 and 5. Those shows will also take place at the Performance Center, so they won’t have audiences for the performers to feed off of or to help guide the pace of a match. Can it deliver the calibre of matches equal to the significance of Wrestlemania in the WWE calendar? Can the promotion learn like Colbert did how to be effective without an audience?

But wrestlers and comedians aren’t the only people working without audiences. Musicians are looking for new musical homes now that the clubs and bars are closed, and many are live-streaming performances online. The Facebook group “Viral Music—Because Kindness is Contagious” gives musicians a place to promote their online shows, but it will be interesting to see who can work effectively without a crowd. Not who can play but who can entertain. Who can think of how to engage the viewer in another room, neighborhood, city or time zone. We have to assume we have at least another month of social distancing, so musicians are going to have to work through these questions if they want to reach viewers online.