Brian Boyles Documents New Orleans' Super Bowl Boom

In this excerpt from his new book, "New Orleans Boom and Blackout: One Hundred Days in America's Coolest Hotspot," Boyles explains the blueprint for a growing New Orleans' tourism economic base.

Brian Boyles' New Orleans Boom and Blackout: One Hundred Days in America's Coolest Hotspot examines the new New Orleans through the lens of the city's preparation for the Super Bowl 2012. His account examines the complicated interaction between government, monied interests, culture and the city and does so with a light but determined touch. Boyles lets people talks words and actions shape how we feel about them, but he doesn't let anybody off the hook.

Thoughout, the Landrieu Administration and civic leaders advance a narrative of recovery that citizens don't always see, and the efforts to give New Orleans a long-term, tourist-based economic future come with a cost. He writes with a wry sense of humor and a remarkable eye for telling details.

Boyles will read from New Orleans Boom and Blackout Thursday at 6 p.m. at Garden District Books. In this excerpt from New Orleans Boom and Blackout, Boyles analyzes the document that guided many of the city's efforts.

In January 2010, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) released “Celebrate Our History, Invest in Our Future: Reinvigorating Tourism in New Orleans,” a tourism master plan commissioned by then-Lieutenant Governor Mitch Landrieu, whose office included the Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. BCG developed the plan with the New Orleans Strategic Hospitality Task Force, a Landrieu-appointed group that included the heads of the Morial Convention Center (MCC), Harrah’s Casino and the Superdome; hotel general managers; restaurant owners; and tourism marketers. The report provided a rare capsule of the aspirations of some of the city’s most powerful interests. Bar graphs and marketing buzzwords mingled with images of horse-drawn carriages and street parades in a twenty-four-page expression of the industry’s vision.

The plan’s executive summary declared, “Tourism: It’s Our Future.” Post-Katrina New Orleans was “not maximizing the opportunities tourism offers—opportunities for job creation, tax generation and cultural renewal.” The industry should use the upcoming fifth anniversary of the storm, the NCAA Final Four in 2012 and the 2013 Super Bowl as opportunities to renew the world’s faith in local hospitality, with each event marked as another step toward the biggest milestone: the city’s 300th anniversary in 2018. The task force set a goal of 13.7 million visitors for that year, an increase of 6 million from 2008. It was an aggressive target, the plan’s authors admitted, but New Orleans faced a choice: “reinvigorate the city’s tourism economy or accept the consequences of a further decline in tourism, including stagnation and weak economic development across all sectors.” In other words, as tourism goes, so goes New Orleans.

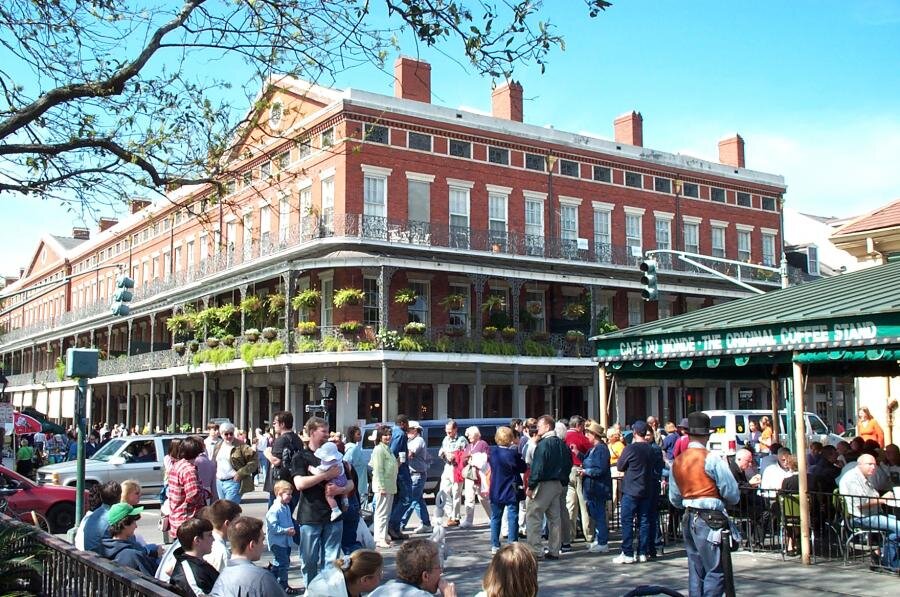

Challenges were legion. “Nonleisure” travel (i.e., business meetings and conventions) was declining in New Orleans and across the nation, so the city needed to dedicate itself to attracting leisure travelers. According to BCG surveys, potential visitors saw the city as “fun for adults” and “authentic,” with a reputation for good food and live music, but added that “crime and Katrina are barriers to success.” New Orleans visitors were older than average compared to peer cities like Chicago, Las Vegas and Miami; Canal Street was struggling; and the airport was “problematic.” The French Quarter remained the “crown jewel,” but safety, code enforcement and cleanliness were all concerns. The city didn’t spend enough on marketing, and the industry lacked coordination. Change was urgently needed to keep New Orleans competitive. “In addition to preserving and enhancing existing assets...New Orleans must adopt new ideas and approaches.”

None of these laments was particularly original, but the assumptions, comparisons and data behind them were revealing. The public—which funded the lieutenant governor’s office and thus the report—was only privy to the executive summary until May 2012. After her public records request was denied, blogger Luna Nola obtained a link through City Councilwoman Kristen Giselson Palmer’s office to 119 PowerPoint slides from a September 1, 2009 meeting of the hospitality task force. Leading the discussion was John Lindquist, a BCG senior advisor specializing in tourism on a global basis and, according to Business Week, an advisor to the World Bank since 2004. The vocabulary and granular analysis of the slides left little doubt: BCG approached New Orleans as a product in need of repositioning. Katrina was no different than other PR nightmares like Mattel’s 2007 recall of toys tainted by lead paint or the deaths from cyanide-laced Tylenol. In each case, companies responded with aggressive spending on ad campaigns, repackaging and media outreach. “Celebrations and special events draw young visitors,” a key demographic, and the 2018 tricentennial had a model: the fiftieth anniversary of Disneyland’s castle, celebrated with $150 million in marketing and a 6 percent increase in attendance. “People have a thirst for nostalgia,” read one slide. To attract tourists, New York fought crime, Chicago tore down public housing and Miami rebranded South Beach. New Orleans could look to countless examples in cities that committed to a focused, well-funded strategy.

The consultants understood the funding challenges faced by the industry. The city invested far less on tourism marketing (about $20 million annually) than Las Vegas and Orlando, and though its 13 percent hotel tax was comparable to peer cities like Chicago and Nashville, higher rates for hotel rooms in those cities generated greater revenue. In other cities, a unified agency directed all tourism efforts, but in New Orleans, various entities received funding through the hotel tax, with the largest portion routed to the state. The biggest share went to the Louisiana State Exposition District (LSED), the state-controlled administrator of the Superdome (31 percent) and the Morial Convention Center (24 percent), while the marketing professionals at the New Orleans Convention and Visitors Bureau (NOCVB) and the New Orleans Tourism Marketing Corporation (NOTMC) were left with 7 percent and 3 percent, respectively, to compete against Disney and Las Vegas for coveted leisure tourists.

In place of the two-headed leadership of NOCVB and NOMTC, the master plan’s Priority A called for a single body to direct the industry efforts. The unified industry would fight for increased funding to market the city nationally and “protect the city’s core assets,” which were the target of Priority B:

“Aggressively focus on basics to revitalize core assets and address weaknesses.” Initiatives included a crime prevention campaign in the Quarter, CBD and Superdome district; improved airline access through more direct flights; enhanced “arrival experience” and reformed taxi service; and “Initiative 4: French Quarter”:

Reinvigorate and revitalize the city’s crown jewel, including Bourbon, Royal, and Canal streets. Efforts should include preserving the historic architecture while repairing and maintaining sidewalks and other infrastructure, adding lighting and patrols to make the areas safe, and ensuring that zoning laws consistent with the desired New Orleans image are established and enforced.

While the other priorities targeted better branding, training for tourism workers and transformative changes to the riverfront, Priorities A and B precluded any future plans. Unified leadership, more money and dependable infrastructure made everything else possible. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the executive summary emphasized the dreams of 2018 and job creation (targeted for thirty-three thousand new jobs, with average salaries of $33,300 by 2018) and left the funding issue to its final pages, where the task force identified seven options for raising funds. These options, the report said, “would require citizen and/or government approval.” Bonds, grants, loans and public-private partnerships would cover one-time investments of up to $405 million, including $330 million in capital projects along the riverfront, Canal Street and in the Quarter. Ongoing “tourism-focused taxes” and a “business and tourism improvement district” would support marketing and operating expenses. The executive summary concluded with a plea for the public’s commitment: “We have the leadership, expertise, and vision to make it happen. All we need is the will.”