Ben Katchor's Sub-Atomic Particles

Comic artist Ben Katchor considers the building blocks of city life in "Hand-Drying in America."

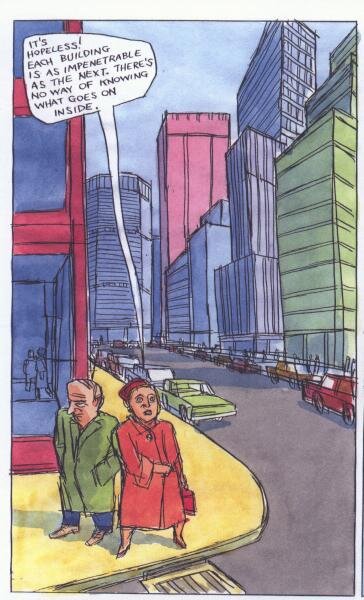

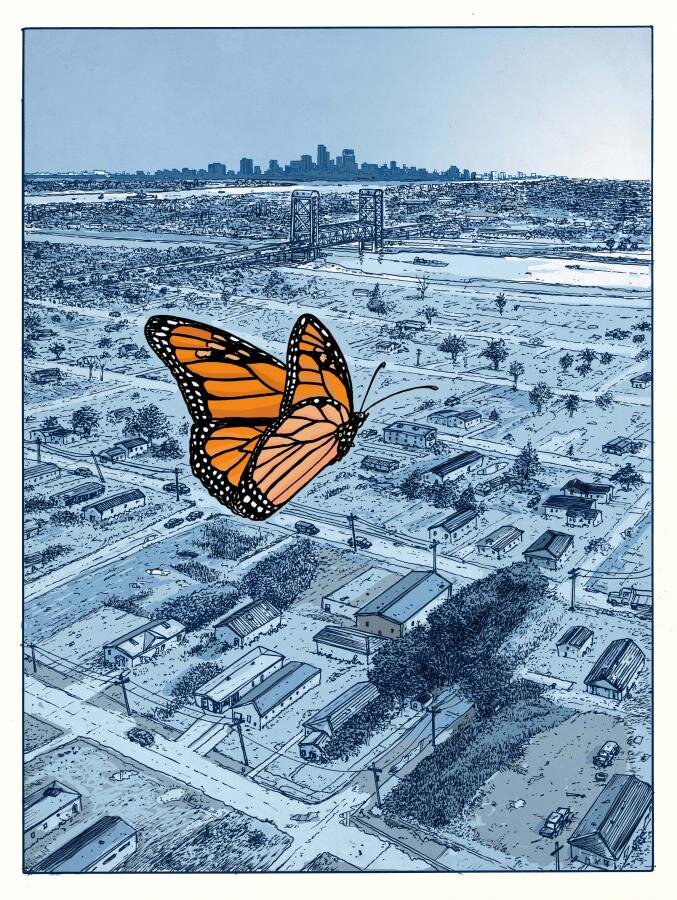

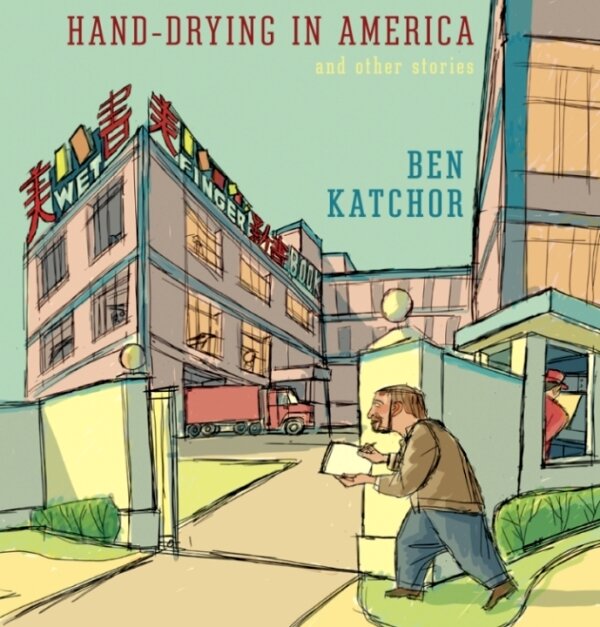

When the WizardWorld Comic Con comes to the Morial Convention Center, Ben Katchor will be among the visiting comic artists. He’ll be easily found; he’ll be the one not drawing superheroes, vampires, or fantasy figures. His most recent book, 2013’s Hand-Drying in America (Pantheon) is a handsome, oversized book of single-page comics that document the small lives of urban dwellers who assert places for themselves through countless quotidian acts. The bad guys—when they exist—aren’t malevolent aliens; they’re resentful minimum wage stock boys and unctuous architects. The heroes, such as they are, win simply by trying to make their lives incrementally more people-friendly. Often, they anatomize their world, nailing down brand names and product details as a way of asserting a measure of control over their lives.

Katchor will also do a signing for Hand-Drying in America Thursday night at 6 p.m. at Octavia Books. As he says in the email interview we conducted, literature was more formative for him than comic books or comic strips, and that’s clear in his work. An atmosphere of loneliness akin to the one turn of the 20th Century American realists created hangs over his comics, which have appeared in alt-weekly newspapers since 1996. When characters talk to each other, they rarely do so in ways that convey intimacy. They frequently aren’t even listening to each other and talk at cross purposes when they talk to people at all.

“We went through 21 billion gallons of jet fuel in 2006,” a flight attendant says apropos of nothing while he “streamlines his body with depilatory cream,” the text above him says.

Katchor’s language is, as that panel suggests, intentionally emotionally neutral, but the pages aren’t. His writing and art are poker-faced, but “Catastrophic Decor” details an absurd reconsideration of home design for eternally anxious. “The Lobby Analgesic” presents a dystopian, darkly humored solution to modern, cost-cutting, office architecture, while “The Providential Twine Center” envisions a casually dehumanizing solution to a problem that could only exist in the corporate psyche. Despite the remoteness of the language, Hand-Drying in America collectively evokes a city very much alive with people who have their own obsessions and concerns, people who are struggling to assert themselves and in small ways succeeding.

How is the comic con experience for you? They’re so associated with superheroes and pop culture, and your work is very different thing.

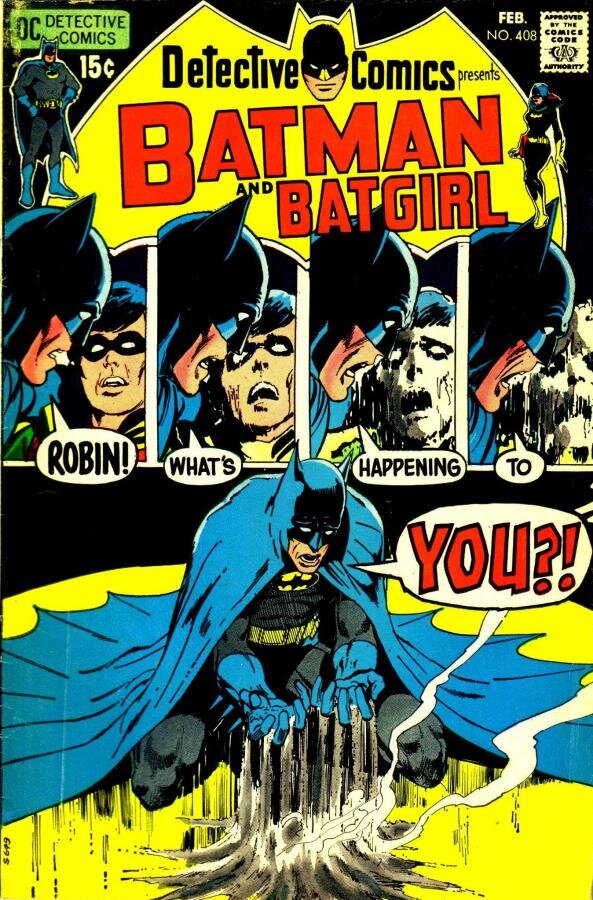

I discovered the Western tradition of figurative art in the superhero/adventure comic-books sold at my corner candy store and so, as a teenager, my life revolved around the mid-70s Academy Comic Conventions in NYC. As I was exposed to the history of literature, painting and cinema, my taste in comics shifted toward underground and experimental work and that work was very much on the periphery of the comic conventions in the '80s--the focus was still on those adventure comics of my childhood.

I don't see much of a commonality between the work I do and the makers of superhero comics. My work is informed by European picture-books and early 20th Century American newspaper comics and the wider cultural influences mentioned above. Superhero comics c. 1938 is a moment in that history and not a very interesting moment in the larger history of comics. In fact, it's that tradition that gave the medium of comic strips a bad reputation. In literary culture, the worst thing you could say about a fictional character was that he/she was like something out a comic strip.

What was your relationship to superhero comics growing up?

I loved the figure drawing and spatial description in the comics of my childhood, but even as a child, I thought that the stories were formulaic excuses for the action scenes. I looked at them for hours, but had little interest in the worlds they were describing.

Did newspaper comic strips mean more to you?

Newspaper comics were in their death throes by the 1950s, but I enjoyed "Dick Tracy," "Our Boarding House," and a few others. Again, my influences were from the larger culture literary fiction, historical painting, cinema etc., not newspaper comics.

In a 2011 A.V. Club interview, you said:

I never liked plots that lull the reader into this kind of coma of entertainment. I’d rather it slap you in the face every page and say, “What plot? Go make up your own plot. Go read a mystery novel.” I’d rather the thing abruptly end every page and say, “Now what are you going to do? Are you going to keep reading this thing? Are you going to go on and burn your passport? What are you going to do?”

Why the antipathy toward plot?

It was the long form "graphic novel" that I was referring to. I like plots, but concise ones that can unfold in a page or two of a strip. I like to challenge myself to come up with a new analysis of some aspect of the world--rethinking the way things operate in this world. That should, ideally, get my reader to challenge him/herself to question their behavior.

Your work often focuses on the small things in a person’s life - overlooked physical details and small, anatomizing thought. Why the focus on the quotidian?

Like a scientist looking at the building blocks of nature--sub-atomic particles, etc.--I feel that the operation of society can best be analyzed by looking at its details and then understanding how these small actions determine the larger picture.

I think about characters in Bobbie Ann Mason’s stories whose speech reflects a similar interest in minutiae and the mundane, and the criticism is that her characters sometimes seem a bit slow or dumb as a result. How do you think about your characters?

Some of my characters are unaware of the situation that I'm trying to demonstrate, but I wouldn't call them slow witted. They're just too distracted by the necessities of life to notice the absurdity of what's going on around them or see an alternative choice of behavior. There's nothing mundane about the study of sub-atomic particles.

I love the loose, sketchy nature of your line, so that panels appear to be rough and provisional but still clearly finished. Where did that come from? Does it have anything to do with your work appearing in alt-weeklies?

My drawing style is based upon the 19th Century appreciation of the so-called sketch aesthetic. It's a kind of drawing that reveals the subtle connection between mind and hand, the accidents involved in drawing. The assembly line approach of pencilling and inking covers this all up with the false surface of bad commercial art.

It has nothing to do with the alt-weeklies. The idea of doing a strip using watercolor tones was unheard of in that print world. It was in the alt-weeklies that I found my audience--people looking at classified ads, reading news articles, etc.--people who would never consider themselves to be comic strip readers.

I think of your work as very urban. Is that simply a function of being a New Yorker and a city person, or is there something more behind it?

Like me, most of the world's population is based in cities and so urban life seems to be an important subject. I did an imaginary travelogue series, "The Cardboard Valise," historical fiction set in NYC and the surrounding countryside c.1830, "The Jew of New York and another series, "Hotel & Farm," one week dealing with hotel culture and the next with agriculture. My father had a farm in upstate NY before I was born and so I have some feelings for that cutlure, as well.

I first saw your work in Raw, which created the impression that there was a community of like-minded artists--you, Mark Beyer, Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, Kaz, and Gary Panter to name a few. How real was that community, and what was the impact of Raw?

The importance of Raw was to present this text-image work in a way that pushed the boundaries of what an art and/or literary magazines might look like--sumptuous production values, subject matter not associated by most people (thanks to 50 years of super hero/adventure comic books) with comics and high editorial standards.

A physical community existed for the few contributors who lived in New York City, and through European contributors passing through the city, but mainly the magazine produced a community of readers and comic strip makers around the world who aspired to making comics that could stand on an equal footing with serious work being done in writing, film and other visual arts. As comics were not an approved art form, as they are now (taught in universities, reviewed in literary magazines, etc.) there was a tremendous pressure on people who chose to work in this generally despised medium to prove its worth and that pressure resulted in a lot of very good work.

I remember a Raw panel during a NY Comic Con in the early '80s. Many of the audience questions were hostile. Why must everything in Raw be so depressing? Why are you taking the fun out of comics? Why doesn't this work look like comics? And so, you see, Raw did not find its audience within comics fandom, but among readers and viewers of other art and literary forms.

Comic book artist Neal Adams will also be at the Comic Con and will do a book signing at More Fun Comics Thursday from 4-7 p.m. Here's an interview I did last year with Adams.