Behind the "Hell"

Rebecca Theim talks about changes at The Times-Picayune and what motivated her to write "Hell and High Water."

Rebecca Theim was not a natural choice to become a prominent voice in the community as The Times-Picayune began its tumultuous shift to a digitial-first strategy. The paper was her second full-time job out of college, but she left it 19 years ago and currently works for an ad agency in Las Vegas. Still, she was active on the Friends of The Times-Picayune Editorial Staff Facebook page, launched dashTHIRTYdash to help staffers who lost jobs, and she the recently published Hell and High Water: The Battle to Save the Daily New Orleans Times Picayune. She will read from the book and sign copies tonight at 6 at Octavia Books.

She got involved for a number of reasons, she says by phone. She had stayed in casual touch with some of the staffers she had worked with, and Hurricane Katrina prompted her as it did many who once lived in New Orleans to reconnect with the city. "When this thing started, I had somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 or 25 people with whom I worked beginning in 1988 who were still employed there," Theim says. "I was standing in my kitchen a year and change ago and it struck me how extraordinary that was when no one stays anywhere."

After The New York Times' David Carr broke the news of Advance Publications' plan to reduce The Times-Picayune to three days a week, lay off staff, and focus first on its Nola.com website, she responded as many with any connection to the paper's staff did - with sympathy and outrage for the unearned struggles they were about to go through. She also admits that some of her activity in support of T-P staff came from a personal place.

"As several of my closer friends in New Orleans have observed to me since then, It seems like you needed this at this time in your life as much as we needed you," Theim says. "There's a great deal of truth in that."

Hell and High Water, she says, was motivated by a desire to have readers understand what those who worked for the paper went through, and why it was so remarkable. One chapter is dedicated to the remarkable, personally destructive (in some cases) lengths staffers went to cover post-Katrina New Orleans, and the paper had a stability that was rare. People stayed as they did, she writes, because the Newhouse family that owns Advance had made what came to be known as The Newhouse Pledge: "No permanent, non-union employee will lose his or her employment because of technological changes or economic conditions so long as you perform your work in a responsible, productive manner, without misconduct, you have completed your probationary period, the newspaper continues to publish daily its current newsprint product and you are willing to retrain for another job, if necessary." It was a way to keep unions out of Advance papers, but it nonetheless made a job at The Times-Picayune a safe and relatively supportive one in uncertain times.

The Newhouses also tended to let locals run local papers. S.I. Newhouse bought family-owned and operated newspapers around the country, but he and his family largely stayed out of the operations of their papers. He bought The Times-Picayune from the Nicholson family, but in New Orleans it was associated far more with the local, old-moneyed Phelps family, with Ashton Sr. and Jr. serving as its publishers for years. According to Theim, that strategy had a lot of positives, but it also exacerbated the community anger after the planned changes were announced.

"Where that hurts them now is that what people perceive to be this quasi-public, deeply New Orleans operation isn't anymore," she says. "It's owned by a company out of New York that's calling all the shots now, and people feel deeply betrayed by that realization, which was always true."

Carr's reporting of the story took Advance and upper management at the paper and Nola.com by surprise, putting them on the defensive from the start, but even after that Theim believes the transition didn't have to be so dramatic. "A lot of people who have been at the Picayune far longer than me and have more knowledge of the inner workings of the place have said this could have been done gradually, subtly and with more nuance and less pain for the staff and could have been successful," she says. Instead, it turned into a PR catastrophe. "I don't think the public relations issues management communication of this could have been handled any more poorly. The only thing they could have done worse is if they had really not treated people well in the severance department," which were above the industry standard.

Since representatives of the Newhouse family and Advance Publications declined to be interviewed for the book, Theim speculates that they made the decision to change the frequency and staff composition to protect the family fortune and change the nature of contemporary newspaper journalism. "It certainly appears Steven Newhouse takes his role very seriously in both of those arenas," she says. That meant not only laying off experienced staff but replacing them with less costly employees with very different, less generous, benefit packages. While it's hard to imagine that ad revenue will continue to pay the bills even with the savings, Theim points to Advance's experience with this plan in Michigan and speculates that it might. "If it didn't show promise and wasn't already showing profitability or close to profitability, I don't think they would have moved forward anywhere else," she says. "They must have felt like they had pretty good data coming out of there to persuade them that this would work elsewhere. It probably is in Birmingham."

Ad revenues are the big question, and the tabloid TP Street appears to be an effort to provide more options for advertisers who prefer print to digital - ads that are more lucrative. Theim was only able to speak on the record with four advertisers, but the changes in frequency affected their advertising strategies. "One of the folks that I spoke to talked about how they were going from seven to three days a week but the rates hardly dropped at all," she says. "In at least three of the instances, the folks said If digital's good enough for The Times-Picayune, it should be good enough for us. Now they're relying on their own proprietary social media memberships or email lists to get word out about things they want their customers to know about."

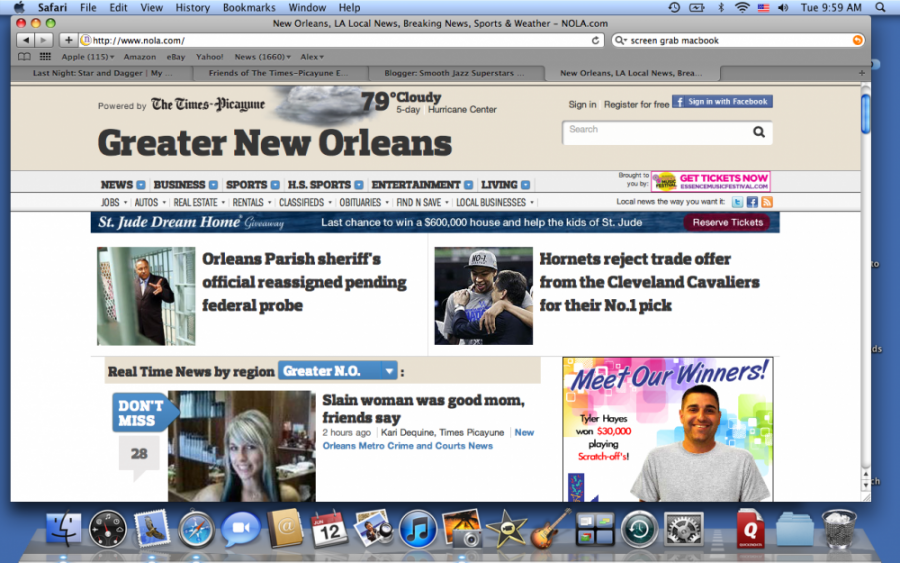

Still, Theim doesn't argue with the theory that the future of journalism is online. "Everybody's migrating that way," she says. "I get that. That's not ever been where my bone of contention was with this. I get an increasing amount of what I read from digital devices." Though Nola.com has undergone a number of changes to address criticisms of it from the start, she remains critical of the site, pointing to The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post as papers with more user-friendly websites. "If you're going to substitute one product for a very good product regarded as one of the very best regional products in the country, the new product needs to be very good."

Like the changes at The Times-Picayune, Hell and High Water was motivated by a number of impulses, some nobler than others. "I miss New Orleans and would like to be able to be formally reconnected to it, even if it's only in a part-time capacity," Theim says. "So, if the book opens a door that would allow me to be there at least some of the time, I'd be thrilled."

But the book also tries to put a human face on what these changes meant. While the changes at The Times-Picayune are part of the process of discovering how thoroughly the Internet will change the way we consume information, they also meant that many people later in life were suddenly faced with uncertain futures. "I wanted it to chronicle to the degree that I could given how many people chose not to speak to me for it, what had happened and put people in that extraordinarily special place and hopefully allow them to understand a little bit of what it felt like to go through that. The content is not the problem. The business model is the problem. This was not the writer's problem. This was the publisher's problem and the editor's problem and the owner of the newspaper's problem. They created this, but the people who were suffering for it were the rank and file - as is the case throughout American business, so I guess that's not a new story. That galled me."

Yesterday, we ran an excerpt from Hell and High Water. You can read about the day the axe fell here.