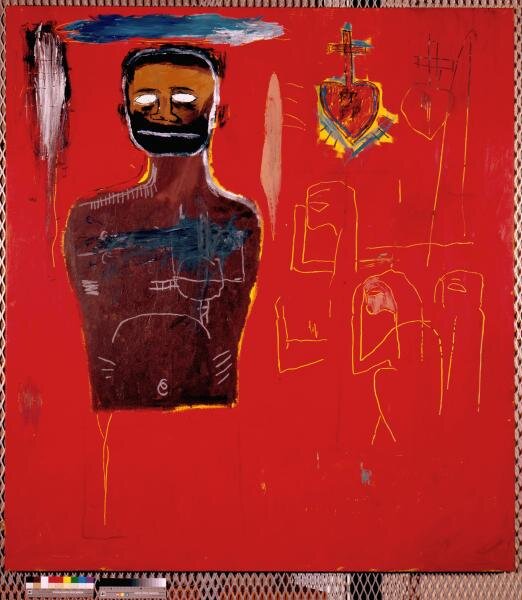

Basquiat's South Came to the North

The Prospect.3 show "Basquiat and the Bayou" shows works by Jean-Michel Basquiat that have roots in the South. But how deep are his southern roots?

In his introduction to “Basquiat and the Bayou,” a show of works by Jean-Michel Basquiat on display in the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Prospect.3 artistic director Franklin Sirmans writes:

The selection of works presented here at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art constitutes a pointed confrontation with the powerful symbolic presence of the Mississippi River and its Delta in the work of this iconic artist. A child of the New World metropolis, Basquiat tussled long and hard with the shadows of the South. In 1988, shortly before his death, Basquiat travelled here on the occasion of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival with friend and fellow artist Ouattara Watts. The expressionistic energy of Jazz Fest and of New Orleans itself—with its roots in Caribbean, African, Native American, and European cultures—finds its visual mirror in Basquiat’s paintings.

Sirmans’ efforts to create a context for a Basquiat show in Prospect.3 are unconvincing. I find it impossible to separate Basquiat from his immediate context—New York City in the ‘80s—and the elements of the South that show up in the works on display say more about how its iconography was received in New York than Basquiat’s firsthand contact with them. The accordion player in “Zydeco” is stylized in the same way that some of Francis Pavy’s are, suggesting that he drew from similar images. The jazz musicians and Zulu figures in “King Zulu” could all have come from a Life or similar magazine story about Louis Armstrong’s reign at King Zulu, and the Br’er Fox image has clearer roots in storybooks and cartoons than anything that happened south of the Mason-Dixon.

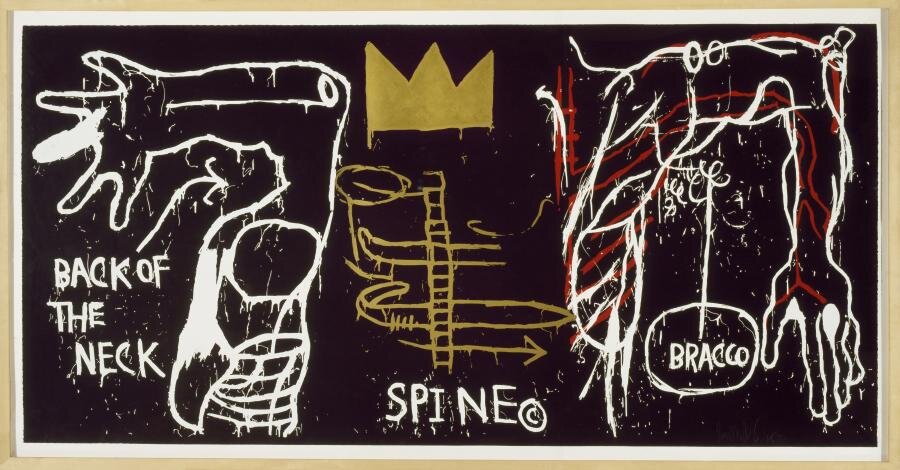

I think of Basquiat as being all about his milieu, the New York art world in the 1980s where lines were blurring: High art/low art, art/artist, art/commodity, and artist/celebrity. Basquiat came of age arts-conscious, and his graffiti tag “SAMO”—a shorthand for “same old shit”—is intentionally ironic since his graffiti wasn’t simply more of the same.

Hip-hop is far more prevalent an influence. We literally see scratching on “Untitled (Cadmium),” where Basquiat appears to have scratched away a layer of red paint with a lino cutting tool to leave trenches in the image that reveal the layer of yellow underneath. He similarly mirrors scratching by only partly painting over an image, appearing to have hurriedly, imperfectly replaced one image with another. Letting the new and old marks be seen is akin to a DJ scratching a record so that you hear part of the song as well as what he or she does to it. The marks feel spontaneous and provisional, simulating the energy created by rapid, percussive, and impermanent scratching.

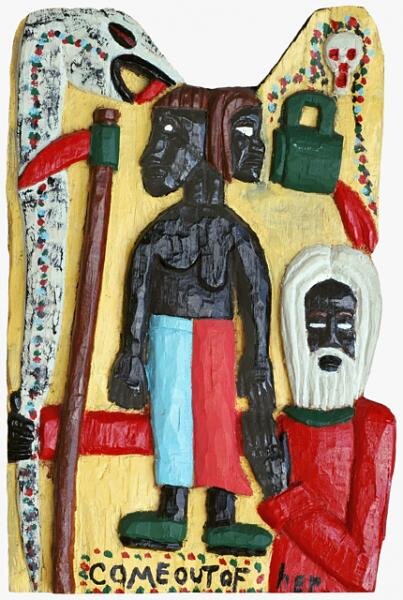

The show of chiseled wood sculptures by folk artist Herbert Singleton points to more relevant references. Basquiat seems more in touch with the work of folk artists and the notion of crude, seemingly unmediated expressions. Basquiat couldn’t be as direct as someone like Singleton because too many impulses seemed to compete for expression in his work. He gave voice to the number one influence in his work—New York itself—as he visually reproduced the cacophonous urban experience in a way that Singleton didn’t.

Sirmans’ text feels like an effort to claim a piece of the Basquiat story for Louisiana and the South that is there only in the sense that it’s present in any African-American alive in the late years of the Twentieth Century who’s at all conscious of his or her cultural history. The icons he chose read in these works more like images of the exotic from another place, time, or sensibility. The suited, shaded horn players in “King Zulu” are isolated in a vague nowhere of blue, but even that is abruptly cut off by the speed of the city, which seemingly forced Basquiat to abandon the piece before it was finished.

Still, the show is valuable because it brings strong works to New Orleans by one of the more mythologized and controversial figures of the art world at the end of the Twentieth Century. I last remember seeing a Basquiat in New Orleans in a pop art show at the Contemporary Arts Center, and one Basquiat isn’t enough to appreciate his work. The Ogden Prospect.3 show has enough range to give viewers an opportunity to make their own connections to his work and pull out their own insights. The lengthy timeline in the hallway outside the show is genuinely useful, and I returned to it a few times to confirm some details. Oddly, the photo outside the show is helpful as well as a reminder of just how young Basquiat was. I don’t entirely buy the premise of “Basquiat and the Bayou,” but it’s still a show worth seeing and a nice keynote address for Prospect.3.