Ann Powers Puts the Body Front and Center in "Good Booty"

In her new book, the NPR music critic pays as much attention to the hips as the head in her history of American music.

Good Booty started organically. As a young woman, editors tended to assign music critic Ann Powers stories on musicians who were young women. Since that beat interested her, much of her writing for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Village Voice, Blender, and most recently NPR continued to deal with gender, including editing and writing the introduction for this summer’s “Turning the Tables: The 150 Greatest Albums by Women.”

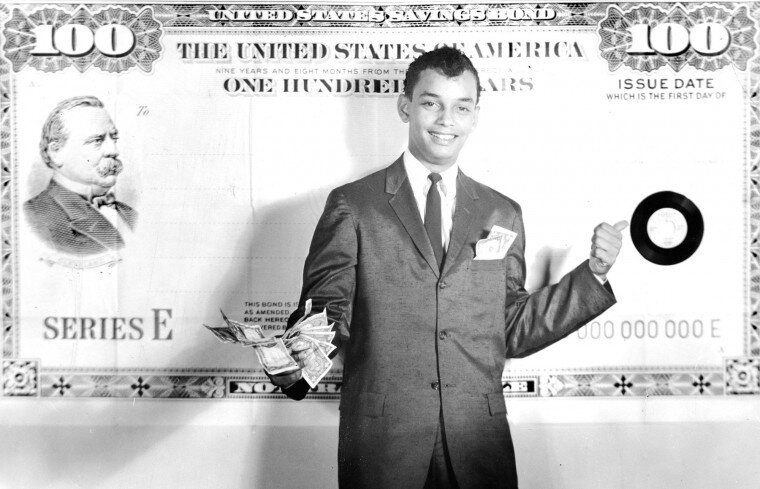

“Thinking about sexuality, which is forever linked to gender but not the same as gender, seemed like a natural route of inquiry for me,” Powers says, and that inquiry took the form of Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black & White, Body and Soul in American Music. She had played for years with some of the ideas that would find their way into the book, but they started to become an actual project when she was asked to speak at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

“The talk I gave was called ‘Rock ’n’ Roll Started with the Shimmy,’ and it was looking at different dance forms.There was always this hip shake, and I traced the hip shake from Antebellum era to the present day—I think that was around the time of the Harlem Shuffle—and twerking,” she says. “That’s my favorite thing to do as a critic, to make connections across space and time.”

Like that Hall of Fame talk, Good Booty traces the interplay between book’s seven sub-titled elements across genres and eras, from Congo Square to Lemonade.

Powers will be at The New Orleans Jazz Museum Tuesday at 6 p.m. where she and music journalist Alison Fensterstock will talk about Good Booty.

Good Booty arrives at a time when the news is full of bad booty—weaponized sexuality used by men to assert power over others. These issues aren’t her book’s concern, but Powers feels that it speaks to them indirectly. “Good Booty is a fundamentally optimistic book,” she says. “I stress the joy and power of music, but I tried in the narrative to temper that with acknowledgements of the struggle, the oppression—that music was not only formed by joy and pleasure but resistance and resilience.” The #BlackLivesMatter movement was often in her thoughts while writing because it challenged her to deal with the legacy of racism as a white woman. “Now we’re in a position when we have to face another difficult, painful truth about our fundamental society, but I think that the book hopefully shines a light on how we in community with each other, as individuals and as a culture, we can still find ways toward self-respect and love and all those positive things.”

Talking about Good Booty in this context brought Jim Morrison to Powers’ mind. The book examines his desire to be seen as a cultural outlaw using sexuality as one of his weapons, but that desire manifested itself in such gestures as exposing himself while onstage in Miami and slapping female fans in the face from the stage. “He as a star showed us something about masculinity that was very unsavory,” she says.

His example explains in part the appeal of writing about figures in our popular culture for Powers. Because we tend to idolize our stars, examining them is a way to understand impulses that we collectively deal with. She used David Bowie as one of the key figures in her chapter on the ‘70s even though he’s not American because, she says, “the transformations he went through told the story I wanted to tell of the era.”

On a personal level, that proved emotionally hard when Bowie died while she was working on that chapter. “The morning that he died, I walked into my office and my desk was covered in David Bowie tour booklets and records,” Powers says. “It was like I’d set up a shrine without meaning to.”

Powers also wrote about Jobriath in that chapter—an out gay man who was signed to Elektra Records with the idea that he would be the next David Bowie. At one point, Jobriath and his music industry macher Jerry Brandt released a statement that read in part, “The drug culture is dead. Broadway is dead. The only thing that’s keeping us alive is sex. I’m selling sex. Sex and professionalism.”

Jobriath didn’t sell much of either, and his story ended after little more than a year in the public eye, but she included him in the book because, Powers says, “I had never thought about the revolutionary aspects of this out, gay artist in the mainstream.”

Lesser known figures like Jobriath are crucial to the way Powers thinks about drawing connections because, in part, they are the people who have traditionally been left out of the American rock ’n’ roll story. The canonical, Rolling Stone-influenced history of rock ’n’ roll tends to diminish the ongoing roles played by women, people of color, and members of the LGBTQ community, so Powers tries to make her work something of a corrective. “In telling those stories, I’m hoping that I can counter the myths of rock ’n’ roll that are sometimes limiting and even destructive," she says.

Good Booty stands, by her own admission, on the shoulders of many writers before her, including the scholars whose work made it possible for her to write the chapters on New Orleans and ragtime. The cross-time and genre reach she attributes to the influence of critic Greil Marcus, and while her writing doesn’t self-consciously counter the Rolling Stone history of rock, Powers has deliberately tried to look at important moments through different lenses to see what other stories and meanings emerge. Rolling Stone’s features and interviews tended to treat great men (usually) as great thinkers, implying that rock ’n’ roll was relevant because it produced geniuses on par with the geniuses in the fields of fine art and architecture. In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s when much of the culture still saw rock as trivial stuff for crazy teenagers, that stance had strategic value, but in the process it gave rock a very conventional canon and muted some of the wildness that gave rock ’n’ roll its character.

“I still struggle personally to find a language that doesn’t go back to these hierarchies of taste or hierarchies of meaning privileging certain types of voice,” Powers says.

“When I was a kid, I was fascinated by “Random Notes” and wanted to know what was going on in all of those scenes. Who was hanging out on the Sunset Strip? Mick Jagger’s going out with Jerry Hall and he used to be married to Bianca Jagger? All those things seem superficial within a certain paradigm, but what if we think about that—the social, cultural life, the private life being performed—as being equally central? That changes the way we think about music history and make more room for people who are normally undervalued and discarded.”

In Good Booty, Powers’ interest in the less told parts of the story gave her an occasion to write about figures she hadn’t before. Although she started her career in San Francisco in the 1980s during the outbreak of AIDS, she had never written about Michael Callen. “He was one of the first artists to talk about being HIV positive, to make music about it,” she says. In Good Booty, she writes, “Even some gay men hesitated to acknowledge [AIDS’] reality, not wanting to curtail the sexual freedoms they’d achieved. Callen was an outlier, discussing his illness from the beginning, the opposite of bigger stars like Queen’s Freddie Mercury, who only confirmed that he had AIDS the day before he died in 1991.”

Surprisingly, the book gave Powers a reason to think critically about Britney Spears for the first time, someone who had never been her beat, even when she wrote for major newspapers. In a chapter titled “Hungry Cyborgs,” Powers considered pop figures whose musical and cultural lives were inseparable from technology. In it, she wrote:

The artists who most influenced Spears also connected a focus on the dynamics of dominance and submission with the plastic new world of cyborgs and cyberspace. Janet Jackson’s 1986 breakthrough album was called Control, and, like Spears, she possessed a vocal instrument that was more synth than saxophone. Working with Prince associates Terry Lewis and Jimmy Jam, Jackson pioneered the connection between the erotic and the electronic, rejecting usual diva displays in favor of a delicate, conversational style that was also highly percussive—a robotic siren call. Her brother, of course, was the master of funky melody. Spears’s love of staccato utterances clearly came from Michael.

“Hungry Cyborgs” reads like the end of the Good Booty, and for a time it was. The challenge of writing about your way to the present is that the present keeps moving though, and for Powers it moved to a place that she couldn’t ignore. Beyoncé’s release of Lemonade in 2016 prompted her to add an epilogue. Powers was at NPR when the album was released, but she didn’t write about it right away. She saw the flood of moving, insightful writing by African-American women on the album, and that gave her a reason to pause. “I wanted to be quiet for a while and listen to what women were saying about Lemonade,” she says. “By the time I wrote the epilogue, I had absorbed a lot of that incredible writing.” Much of the writing that inspired her can now be found by searching the #lemonadesyllabus hashtag on Twitter.

The epilogue also allowed Powers to speak directly to the turbulent political climate that helped to shape the book. She saw #BlackLivesMatter in her text but was concerned that others might not unless she addressed it more explicitly. In Good Booty, she says, “I started to think about how to tell this story of how music helps people be in their bodies, helps people express what was happening in their bodies, connect through their bodies to each other, and how in different moments we deal with issues that come up around our bodies through music.

“#BlackLivesMatter made us witness the vulnerabilities of our bodies. Our bodies are also so vulnerable.”