Addy Najera Is Just Trying to Have Some Fun

Can a stand-up comic get anywhere when things are going well?

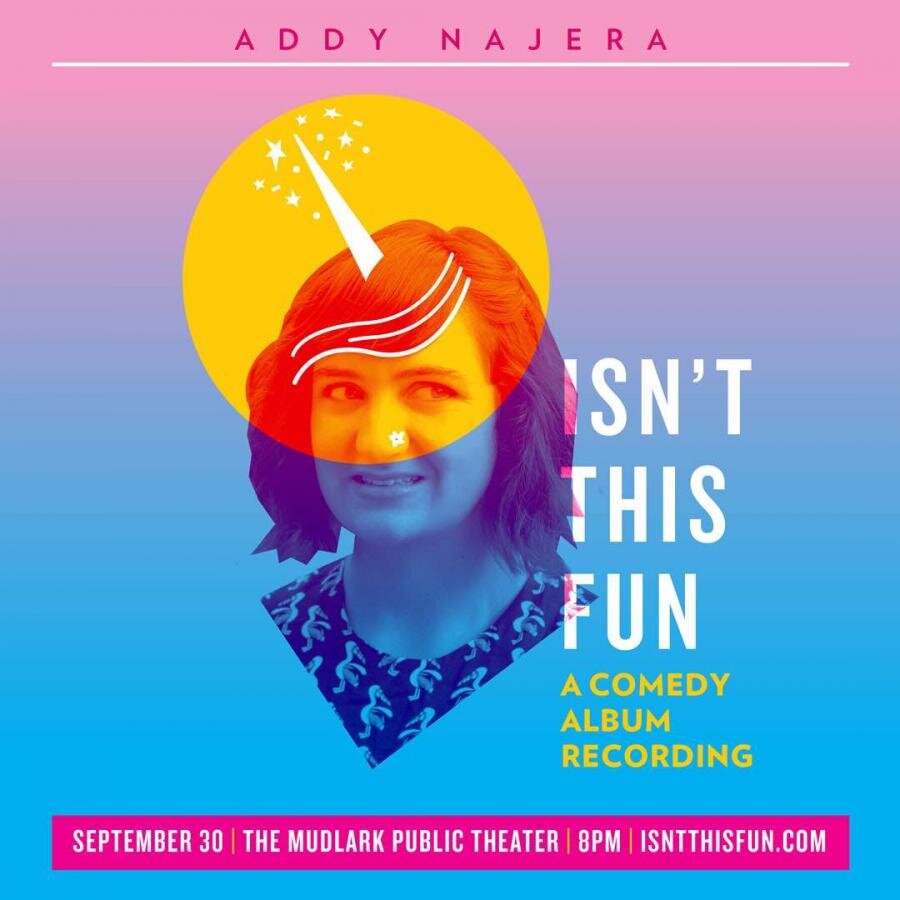

Tonight, Addy Najera will record her first comedy album, Isn’t This Fun. It’s not something she’s dreamed of, though. Najera has no fond recollections of memorizing Steve Martin routines from A Wild and Crazy Guy, or of having new worlds opened to her while listening to albums by George Carlin, Joan Rivers, Sam Kinison or Margaret Cho. She did connect to Richard Pryor—“He’s so brutally honest that that will never not feel shocking and truthful to people”—but that came after she started performing comedy. She doesn’t think of a comedy album as a way to join a tradition or make an artistic statement.

“When you’re not in New York or Los Angeles, you need to set milestones for yourself,” Najera says. “New Orleans is a really creative place, but when it comes to the business of being a successful artist, you have to set your own milestones along the way. I want to compile the best stuff that I’ve done and put it in one place.”

Najera will record the album when she performs at The Mudlark Theater tonight with Cyrus Cooper and Julie Mitchell opening, and the show will be a culmination of five years of her first five years as a stand-up comic. She was one of finalists earlier this year at “Hell Yes Next,” the search for the top comedian in New Orleans, and has opened for Judah Friedlander, Aparna Nancherla, Sean Patton, Janine Brito and Sarah Schafer. In 2015, the Mental Health Network’s Cracking Up included her among the performers it focused on as it examined the intersection between comedy and mental health.

All of her success came out of a desire to make friends.

Najera moved to New Orleans from Massachusetts in February 2011. When she arrived, she took improv classes through The New Movement, more to meet people than to scratch a comedy itch. She was bouncing from job to job and scene to scene in New Orleans, which made it hard for her to find her people When that year’s Hell Yes Fest rolled around, she volunteered to help out, and that led to hanging out with the comedians, which she loved because they were so funny. It helped that they found her funny too. Their encouragement prompted her to finally perform at her first open mic.

“I got caught up in getting compliments,” Najera says. “I was like, They’re telling me to do it. I have to do it. They’re so cool. After that, I looked back and thought, Oh yeah—I should have thought about comedy sooner.”

The improv class wasn’t a completely random starting place, though. In college, she tried out for a campus improv troupe but didn’t make the cut—a judgment she now understands. “Of course I didn’t make it,” she says. “I didn’t know what I was doing.”

Not only does Najera not go misty-eyed over the great comedy albums, but comedy wasn’t an obsession growing up. She doesn’t have favorite casts of Saturday Night Live, and her comedic blank-slateness means she doesn’t feel the anxiety that decades of comedic genius before her can create. Not knowing the great comics and sketches and sitcoms creates challenges, though. “I have nothing to go on,” she says. “I don’t know what I’m trying to do, but in some respects that gives me an advantage because I’m not trying to be like anybody. Trying to figure out out for the first time makes it all more magical.”

To prepare for tonight’s show and prospective album, Najera has had to go back through old material to find bits she wanted to resurrect. In some cases, the experience was embarrassing, but she also admired well-constructed jokes that she wrote when younger. She’s had to streamline some of them to make them more efficient and funny, but the one thing that they all have in common is that they reflect her point of view. That seems like a given for a comedian, but it’s not.

“I’ve written jokes where I’ve said to someone, You should say that because it sounds like something you would say,” Najera recalls. “If don’t feel like I can say something with conviction, I’m probably not going to do it.” One such joke centered on her father, and she introduced it at an open mic. She loved the joke as a joke, and so did the audience. It killed, but it also made her uncomfortable because the joke make it sound as if she didn’t love and respect her dad. “I didn’t think I could say it over and over,” she says. “That’s the only time I’ve had a real second-guess about a joke that I’ve told. I’m not thinking that much about my brand.”

The lack of a strong history with comedy also keeps Najera in the present. Comedic styles change, and while funny may be funny, how hard and knowingly you laugh changes. Seinfeld’s observational humor now seems parental, and stand-ups from before him have in many cases dated worse. “I just wanted to talk about myself in a funny way,” she says, and she succeeds in doing so without going to familiar places. Her comedy rarely sounds like therapy disguised as entertainment, and she doesn’t adopt a Poor Me stance, particularly in regards to her love life. Najera talks onstage about having a good relationship and a good job and finds humor in that. Her comedy isn’t about the struggle to be happy; it’s about the effort to be happier.

“I like to think that my comedy comes from a place of joy than misery. I’m actively trying to be a better person, a happier person all the time. If you’re not, I’m not sure what you’re doing with your life.”