Michael Tisserand's Krazy Story Reaches from New Orleans to Coconino County

Comic strip artist George Herriman kept his New Orleans origins a secret throughout his life, but you can see it a careful read of his comic strip, "Krazy Kat."

Michael Tisserand’s road to Krazy was not a fast one. He knew that George Herriman, the comic strip artist who created the classic “Krazy Kat" was from New Orleans, and although Herriman had been cagey throughout his lifetime about his ethnicity, Tisserand suspected that he was African American, even though Herriman identified as white. Tisserand wondered if the games that Herriman played with race in “Krazy Kat” were an extensions of ones he played with greater stakes in his personal life.

Tisserand wasn’t the first person to consider the possibility, but Herriman successfully passed as white from his birth in 1880 until he died in 1944, and it wasn’t until 1971 that people began to retroactively consider that Herriman might not have been Greek, as his early newspaper nickname “George the Greek” suggested.

Not surprisingly, it wasn’t easy to write the biography of someone whose secret, if discovered, could have ruined his career. Herriman didn’t leave behind a trove of revelatory documents and journals, nor did he discuss his secret with others. Still, Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White finally saw the light of day after almost a decade of work last December, and Tisserand will talk about Herriman and his book Friday at 10 a.m. as part of a panel on “Larger Than Life Stories in New Orleans” at the Tennessee Williams/New Orleans Literary Festival.

Today, the creator of “Krazy Kat” might seem at first like an odd choice for a biography. Herriman’s fame is not only tied to newspapers, but a newspaper world that hasn’t existed for more than 50 years. When we see comic strips in newspapers, we often see little more than the two or three characters central to the joke in a two or three-panel set-up to to a final gag. Backgrounds are sketchy when they exist because the panels can easily seem crowded or confusing at the size they are published.

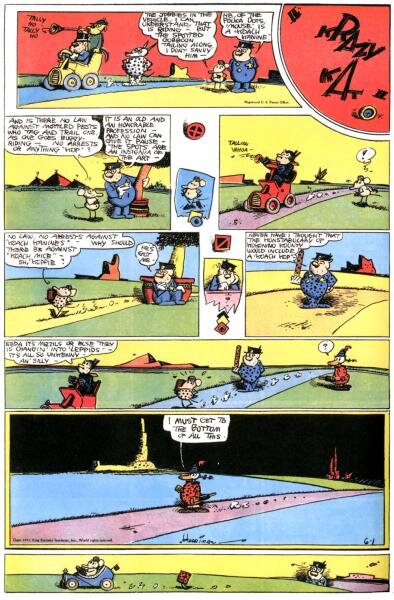

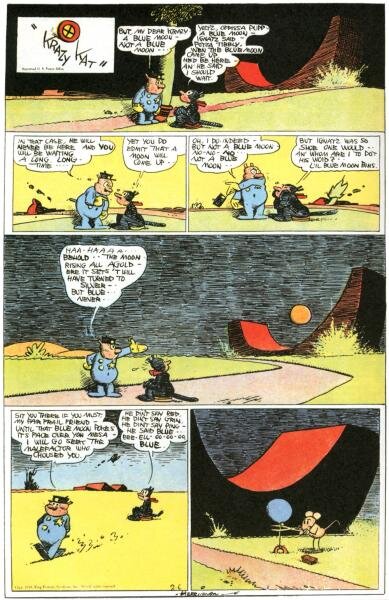

Herriman usually had at least a half-page to work with if not more when “Krazy Kat” ran from 1913 to 1944. That allowed Herriman to draw beautiful buttes and landscapes inspired by the Arizona desert, and they established the tone of a place where magical things—including magical thinking—can happen. In that space, Herriman could tell stories imaginatively, playing with lay out and often dispensing with the grid of rectangles that have been the default format for newspaper comics almost from their inception.

Because of that, Herriman’s work has been reprinted infrequently, and rarely as it was meant to be seen. In 2010, Sunday Press published George Herriman’s Krazy Kat: A Celebration of Sundays, the coffee table-est of coffee table books that generally reprinted the comics at their original size. Fantagraphics Books began reprinting “Krazy Kat” in a series of trade paperbacks in 2002, but unless people traveled in the specialized circles where those books might appear, generations are forgiven if “Krazy Kat” is new to them.

Tisserand edited Gambit in 2005, and the Fantagraphics series sat on the floor of his office when the post-Katrina flood waters rose and entered the alt-weekly’s Mid-City offices. (Full disclosure: I worked with Tisserand at the time, and was as giddy as he was when the Fantagraphics box arrived.)

“Those all got washed away,” he says, laughing. “Those became pudding.” Herriman’s story stayed in the back of his mind after Tisserand relocated to Chicago for a few years after Katrina, and while there in 2006 he saw “The Masters of American Comics” show in a museum in Milwaukee. “The first room was all [Winsor] McCay, the second room was all Herriman.” The implied project of the show was to create an American comic art canon, and that impulse resonated enough for Tisserand to move his affection for Herriman and “Krazy Kat” into action. If Picasso and Rembrandt merited biographies, so did Herriman.

By 2006, that belief wasn’t the reach that it had been thought to be in previous decades. Even into the ‘70s and ‘80s, high art/low art distinctions had some currency, and “low art” was often read as code for pop culture trash someone wants to elevate. In the field of newspaper comics, it didn’t help that the artists themselves saw themselves as newspaper men, which was certainly the case with Herriman. He got his start in newspapers doing comics to illustrate sports stories, and that remained his bread and butter for the first decade of his career as he tried out countless daily strip ideas, most of which were derivative and only lasted for a few months.

Tisserand believes Herriman was conscious of himself as an artist—it was an argument that critic Gilbert Seldes famously advanced on his behalf in 1923 in his book The Seven Lively Arts—but Herriman was also aware of the utilitarian nature of his work. In a letter written to friends late in his career, he wrote, “I’ve got a heap of work … and yards and yards of blank paper to put comical pictures on, so that Mr. Hearst’s customers can laugh in there [sic] eggs and coffee every morning.”

Some of that humility was simply Herriman. “[“Krazy Kat”] is the work of someone very confident in his own vision, but he was also well aware that it didn’t connect with readers the way it was supposed to connect with readers,” Tisserand says. “The way he felt about his own work frustrated his friends. You’re a genius! How many times do I have to tell you? Look—Vanity Fair! Look—Esquire!”

When Nelson George reviewed Krazy for The New York Times Review of Books, he wrote, “Though Tisserand does a truly exhaustive job detailing Herriman’s private and public lives, the promised analysis of race in his vast catalog of ‘Krazy Kat’ cartoons is more fleeting than intricate.” Tisserand understands the criticism and considers not only fair but understandable. “Krazy Kat” begs for interpretation, and Herriman’s pre-“Krazy Kat” strips similarly leaves readers wanting even a spitballed take as to what was going on—a take Tisserand generally avoids.

“Once you start, it’s hard to stop,” he says, and he specifically wanted to write a different book. He wanted to bring his background in journalism to Herriman’s story to clarify, flesh out, and in some cases correct the record where Herriman’s life is concerned. “I chose not to try to tell the reader what I thought was in Herriman’s head,” he says. “My approach for better or for worse was to present his comics and present his life like a tour guide, showing a flashlight over there and over there, and let the reader make the connections that the reader sees.”

Approach considerations aside, Tisserand also avoids stepping in Herriman’s shoes to explain him because he came to realize his limits while researching the book. “Herriman has a way of staying a step ahead of you,” he says.

At some point while working on Krazy, Tisserand half-jokes “that I entered an emotional valley.” He had set himself the task of telling the story of a man who had strong incentives to leave behind as little of himself as possible while alive. Because of that, Tisserand had to find other ways to get some insight as to who Herriman was. He mapped Herriman’s comics to the time line of his life as exactly as possible to see what light they could provide, and he had to rely on what interested interviewers, the people who knew him, and him in the few letters that remained.

That led to some emotionally extreme moments such as the elation that accompanied the discovery of an interview with Herriman followed moments later by a cratering feeling when he saw that the interviewer didn’t to the in-depth, Playboy-like interview he thought he’d found, and instead asked for funny stories from his newspaper career. In a more revelatory interview, Herriman did talk at length about his affection for the setting of “Krazy Kat.”

“He considered the scenes of Northern Arizona and Southern Utah to be as important as any of the characters,” Tisserand says. “I think that discovering Coconino County and Navaho County and his time in Arizona and his embrace of the beauty that he found there and spent much time with—not only the landscapes but the people he found there, the settlers as well as the Navaho or Diné people that he spent much time with—that entered into ‘Krazy Kat’ in a profound way. My interpretation is that that brought him out of the racial binary that he entered into after he left New Orleans.”

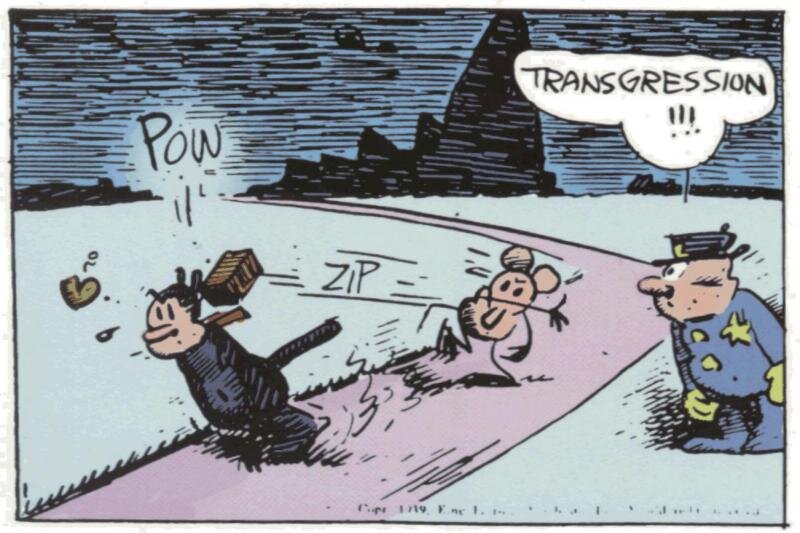

In “Krazy Kat,” Herriman brought New Orleans’ love of play to a profound level. Nothing in the comic is nailed down—not gender, not race, not even the strip’s internal reality, but the result is poetic, clear, and real in the ways that count. Tisserand doesn’t think Herriman stumbled into his achievement. “It wasn’t just that he was having fun in this artistic, literary, surrealist, dadaist way,” he says, “bringing all these ideas of artistic dislocation into the funny pages. He was aware of all of these movements in art and participated in them. He wasn’t this outsider artist, but he was also a member of this don’t ask/don’t tell culture when it came to his own race.”