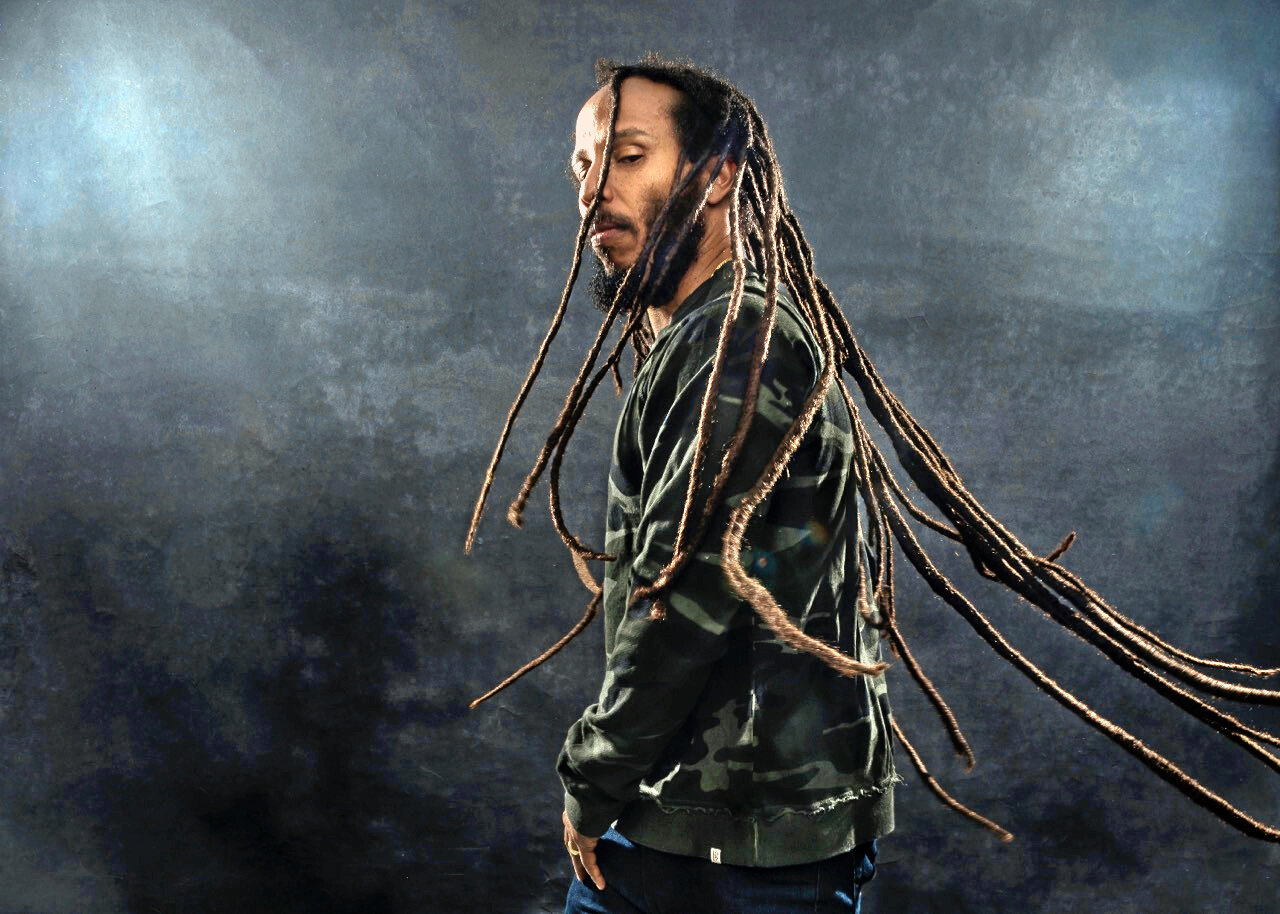

Zachary Richard Rediscovers His Parents

While recovering from a stroke, the LEH's Humanist of the Year came to understand his mother and father's humanity in a new way.

Zachary Richard didn’t think it would work.

The Cajun musician and activist suffered a mild stroke in October 2010, and because of it he was paralyzed on his left side. A month before the stroke, he’d gone in for a physical and the doctor congratulated him on starting his 60s in such good shape, but it happened anyway.

“They called it a random event,” Richard says. “They don’t know why. Some kind of mechanical failure. A bad yoga move. Nobody knows why.” He remembers his therapist telling him, “Tell your right foot to move your left foot. Move your right foot and think about your left foot,” which seemed crazy at the time. Still, Richard took the doctor’s advice and “one morning, I moved my foot.” Once that happened, he was determined to get out of the hospital as soon as possible.

“Good health is based on good food and good rest, and you don’t get either in a hospital.”

From the start, Richard was impatient. The day after the stroke, he told the doctor he was scheduled to be in Vancouver the next day and wondered when he could leave. When Richard asked a nurse what the record was for checking out after a stroke, she tsk’ed and said she couldn’t tell him that. When she rolled him out, she leaned over his shoulder and whispered, You got the record.

As Richard began to regain use of his arm and leg, he played piano—not because he was good at it or feared losing that talent, but because it was good exercise. “I played left-hand scales for two hours every morning just to be able to get those pathways,” he says. “I’m not a piano player, but I love to play the piano.” His doctor had told him the day after the stroke that he would make “a complete recovery,” but Richard didn’t realize that he was speaking in medical terms, where the phrase meant that he would walk, talk and feed himself.

“I took that to mean that I’d be able to go back to where I was,” he says and took steps to make that happen.

Recently, the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities named Zachary Richard its Humanist of the Year. The recognition goes to “the individuals and organizations making invaluable contributions to the culture of Louisiana.” Richard, they write, “is a world-renowned singer-songwriter, poet, documentary film producer, cultural activist, and environmentalist. In a career that has spanned more than four decades and has seen him write, perform, and record in both English and French, Richard has released more than twenty albums, including multiplatinum and gold records. He has authored four collections of poetry, in addition to a series of children’s books.” He’ll be one of the people honored at the LEH’s 2016 Bright Lights Awards Dinner April 7 at the Marigny Opera House.

“I’m still writing, I’m still playing. I’m as active as I want to be,” he said after the announcement. The recognition comes at the end of a difficult period because even though Richard recovered physically from the stroke, the anxiety over whether or not he’d be able to play and sing again lingered. In 2011, he pinned his hopes for healing to the recording sessions for Le Fou, which he recorded in Montreal. He had developed a second career in French-speaking Canada over the last two decades, one that reflected his more mature self than the Cajun rocker he was in the ‘70s and ’80s. Cap Enragé, his 1996 album went double platinum there, and he is enough of a figure to share a stage with Celine Dion and get her to sing on his album, as she did on 2009’s Last Kiss.

He approached the sessions as if nothing had happened, and at one point he decided to take a break and enjoy a half-hour in the sunshine on a beautiful day. There was a beautiful cemetery nearby with grand, architectural tombs for Anglo-Scottish families in Montreal, so he rode uphill to it as he had many times before. He stopped at the tomb of the Molsons including Harry Molson, who had died on the Titanic. On the way back, he stopped to talk to some workers about the health of the trees—“you’ve got to stay engaged in life”—then got back on his bike and sped down the hill until the car of a worker in the cemetery pulled out in front of him. He went over his handlebars, landed on his right shoulder and arm, and ended up back in the hospital briefly.

“I spent that album on the couch of the studio on painkillers looped out of my head. The lower back and hip problems were much worse than the stroke.,” Richard says, and the effects of the accident have lingered longer. That fall came almost a year to the day after the stroke, and he couldn’t help but think that something was up. He’d never seen the workers in the cemetery before, and if they hadn’t been there, he’d have left sooner. If he’d have left five minutes earlier, the car wouldn’t have been there and nothing would have happened.

“For three years, I was scared,” he says. “I guess it’s what they call Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome. I stayed depressed. I was convinced I was never going to do anything worthwhile, that I had never done anything worthwhile.” Eventually, he thought, I’ve got to enjoy my time more than this and started to come out of it.

While his own health improved, Richard spent more and more time taking care of his 94 year-old mother. Unsure of what to do with her, he began to help her organize her photographs, Her family had a camera when she was young, so she had a pictures of herself as a baby, as a student in grade school, and at all the personal milestones that serve as domestic photo ops. Richard has spent his professional life exploring Cajun culture from its roots in Canada to its manifestation in Louisiana, and though it wasn't his intention when he began sorting out his mother’s photos, they fed into that.

The pictures had notes on the back that his mother wrote when she sent them to Richard’s father, who was stationed in the Panana Canal Zone during the war. The letters didn’t survive, but the photos remain as evidence of who this young married couple was at the time.

“My mother had beautiful handwriting. My father did too,” he says. “What’s interesting to me is how Anglo-American they were. Lotsa love, they said, and all these American terms because they didn’t know how to write French. It was not their language.” Richard grew up communicating with his grandparents solely in French because they didn’t speak any English, but their children—Richard’s parents, aunts and uncles—spoke to him only in English. His parents were part of the generation of native French-speaking Louisianans who had the French beat out of them in school, but one thing Richard didn’t see in their correspondence was bitterness.

“They were just communicating as two Americans,” he says.

Ironically, that put them in a slightly different place from Richard. He is personally, professionally, and emotionally tied to Cajun French in a way that they were not. “As a French language author, my relationship to French is fundamental,” he says. He’s pleased that now there are more people than ever who read French here, but the state’s relationship to the language remains complicated. “There’s no way we can go back to where we were in 1900 when, according to the census, 85 percent of Southwest Louisiana was monolingual French-speaking. On the American census report, they’ve got Foreign Language. We’ve got people in Louisiana who are speaking a so-called foreign language. How did my grandparents relate to that? How did they feel about the forced assimilation of their children? Because education was something that they valued tremendously. The fact that it was in a language they didn’t understand must have been a problem for them. They couldn’t help their kids with their homework. They couldn’t communicate with their children in the language that they were learning.”

Going through his mother’s photos and recording her stories on his phone gave Richard a new perspective on his parents. He stopped seeing them as an extension of his own story or as part of a culture under attack, and instead connected to them as individuals. “I had a lot of love for these people, and to realize the depth of their humanity and to see them not as an old 94-year-old invalid but as a 24 year-old woman having a helluva good time—” he says. “Most touching to me were pictures of my parents when they were just starting to date. You have these obviously very happy people.” The notes on the back of the photos that his mother sent his father were often pictures of herself. This is my new dress; how do you like it?

The photos, the notes, and her stories made their lives as young adults real to Richard in a way that they had never been. “They’re so obviously in love and having a good time with their lives,” he says. His mother remembered his father waking up and dancing around the bed during the first weeks, maybe months, of their marriage, and that story was a revelation for Richard.

“My father was a fun-loving man, but I can’t imagine him jumping out of bed dancing.”

At the LEH press conference, Richard said, “We’re in the beginning of Lent. Just a couple of days ago, at 9 o’clock in my front yard, there were 50 people acting the fool, dressed up, dancing the Mardi Gras, and it struck me what a wonderful place I live in. I’m so fortunate to be part of this culture. I love Louisiana. I love being part of this experience which is so extravagant, so extreme, and so bitter and so joyful at the same time. To be able to express myself in the language of Louisiana is one of the most important gifts that life has ever given me.”

If you're considering purchasing any of the albums mentioned in this story, buy them through the links on this page and My Spilt Milk will get a piece of the action. Thanks.